On Dec. 24, around noon, Abdul Sharifu’s phone rang. A woman without a car needed milk for her baby.

Among the Congolese community in the city, 26-year-old Abdul had earned the nickname “911” for his willingness to assist those who needed support, picking up groceries, driving people to doctor’s appointments, or dropping them off at work. Buffalo’s unofficial moniker is “The City of Good Neighbors,” and Abdul was certainly a neighbor you could rely on.

“You call him and he’d be there quick,” his cousin Ally Sharifu said.

“He talked to anybody and helped everybody,” his friend Djumpili Djouma said.

Abdul’s wife, Gloria, who was eight months pregnant, urged him to stay home. A blizzard, one of the worst to hit the city in decades, had been raging since the previous day. But if Abdul didn’t offer a hand, who would? The storm had knocked out power in some households. The city announced that emergency services were backlogged. The mayor warned that the thick snow drifts, icy roads, and toppled trees would likely bring the city to a standstill for days to come.

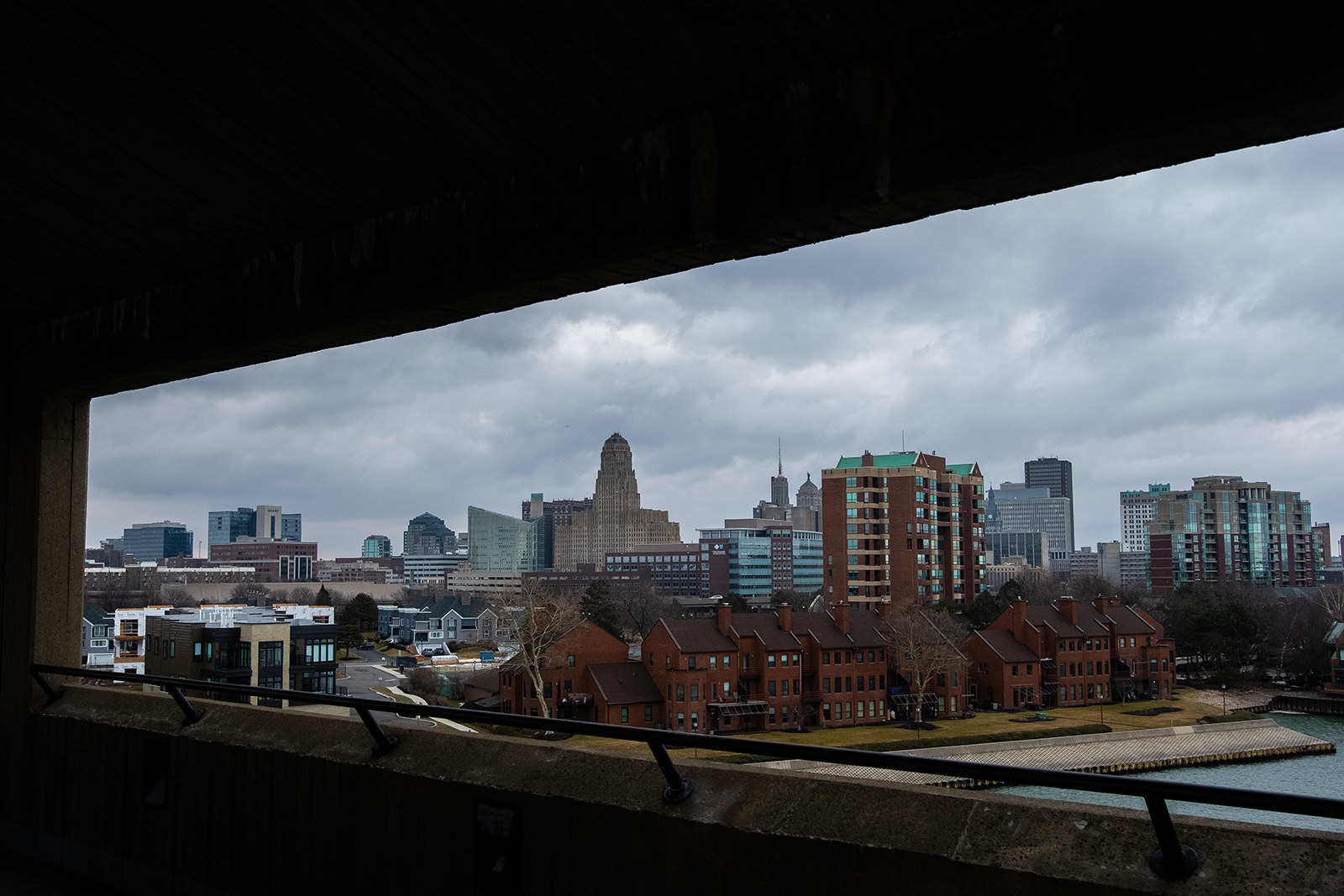

Gregarious, friendly, and quick to make jokes, Abdul embraced his role in the community. After arriving in 2017 with his cousin Ally, Abdul came to embody the spirit of a city that has forged critical support systems in the vacuum left by institutional neglect. As he settled in, Buffalo was striving to escape its hard-luck reputation as one of the most racially segregated and economically disenfranchised cities in the nation.

The steel mills and their well-paid union jobs were mostly gone, but in their place eventually bloomed one of the most robust labor movements in the country: In 2021, local Starbucks employees sparked an organizing campaign that has resulted in nearly 300 of the company’s branches unionizing nationwide, and in early 2022, workers at the local Tesla plant began efforts to form the first union in the company’s history. A socialist candidate who vowed to defund police nearly unseated the four-term incumbent mayor, Byron Brown, in the closely contested 2021 election. Young people from around the region have been moving into the city, drawn by affordable housing costs, a burgeoning arts scene, and an expanding food culture. They carry ambitions to help transform Buffalo into a bastion of tolerance and equitable social policies.

At the center of all the changes were residents like Sharifu, landing in Buffalo from every corner of the globe. After decades of Rust Belt exodus, the city had in recent years opened its doors to refugees, who filled vacant storefronts with new businesses and invited loved ones to join them in their new home. For the first time since the 1940s, Buffalo’s population is growing. A city long anchored by its past now offers a possible glimpse into America’s future, rooted in its people’s collective belief that while the institutions around them might fail, they can always count on one another.

To Abdul, turning down a neighbor in need wasn’t an option. He put on boots and a thick winter coat, trudged through the snowbank rising on his front lawn, stepped into his red Toyota SUV, and drove into the storm.

On their flight into the city six years ago, Abdul and Ally Sharifu looked out the window and saw only white. Buffalo was coated in snow, which the young men had never seen up close.

Born in Kalemie at the eastern edge of the Democratic Republic of Congo, they were small children when their parents were killed in the country’s civil war. An auntie shuttled them over the border to Burundi, where they lived with her in a refugee camp for more than a decade, awaiting word from the international organizations tasked with finding them a place to permanently resettle.

“Sometimes you don’t believe you will find a new home,” said Ally, two years older than his cousin.

They found work with a bus company. Ally drove while Abdul collected passengers’ fares. Their boss paid them around 16% of each day’s revenues.

Then one day, out of nowhere, they learned that the United States had accepted their applications for asylum, though not their aunt’s. A plane carried them to Washington, DC, where they spent a night at a hotel marveling at the pristine buildings and commercial abundance around them. “This place is so good,” Ally remembered thinking. The next day, they boarded another plane, which took them to Buffalo, the second most populous city in America’s fourth most populous state.

Buffalo had become a common destination for refugees since the turn of the millennium, part of the local government’s plan to bolster its declining population with waves of new arrivals who were brought in through four resettlement organizations based in the city. Within two decades, a city that had one of the smallest immigrant populations of any its size transformed, boasting residents from Somalia, Nepal, Yemen, Ethiopia, Myanmar, South Sudan, Iraq, Rwanda, Bhutan, Liberia, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Congo, and elsewhere — a migration pattern that reflected a timeline of the world’s varied conflicts. From 2006 to 2013, the city’s population of foreign-born residents nearly doubled. Over the last two decades, more than 16,000 refugees have made a home in Buffalo, creating magnet communities that have subsequently drawn immigrants looking to settle in an American city with familiar faces, languages, and support systems.

A refugee resettlement program placed the Sharifus in a house on the city’s East Side, where 85% of Buffalo’s Black residents live. The program covered their expenses for two months, enrolling them in classes teaching English, which they didn't yet speak, and connecting them with work opportunities. Ally started working at a plant manufacturing plastic products. Abdul got a job at a sugar refinery, and then as a machine operator at a factory producing pharmaceuticals.

Dropping into a new place where he didn’t speak the language or understand the customs left Ally uncomfortable. For the first few weeks, he rarely left the house. “I was too scared to go outside,” he said.

“Why you always stay inside every day?” he recalled Abdul asking him.

“These are people I don’t know,” Ally replied.

“The longer you live with them, the more you will understand them,” Abdul said.

On Abdul’s urging, they began taking walks around the neighborhood, and then around the city, exploring downtown and meeting people at MLK Jr. Park and the Chinese restaurant on Broadway. Working full-time jobs that often left them exhausted, they dropped out of the weekly English classes after six months and instead picked up the language through immersion.

Though they had arrived in a city where they knew nobody, many of their Congolese friends from the Burundi camp were making their way to the States, part of an Obama administration effort to welcome in more refugees. A woman Ally had a crush on landed in Colorado, then joined them in Buffalo, where she and Ally got married. Another friend, Justin Kahoro, landed in Florida, before making the trip north to move in with the group. The four of them squeezed into the two-bedroom house, with Ally and his wife in one room, and Abdul and Kahoro in the other.

Their circle expanded from there. Through old family ties, Kahoro knew another Congolese resident in Buffalo, Enock Rushikana, who had arrived a decade earlier and introduced them to other expats. Rushikana owned a couple of vacant houses on a narrow street on the East Side. Ally and his wife moved into one next to him, and Abdul and Kahoro moved into another one a few doors down. The block quickly became a social hub, alive with dinner parties, summer barbecues, and cozy winter gatherings around living room televisions.

With a steady job and his first kid on the way, Ally signed a lease on a car. He hadn’t foreseen how such a simple decision would suddenly make him the most popular member of their newfound community. Soon, he was getting calls nearly every day from friends, friends of friends, and relatives of friends asking for favors that required a vehicle. He was happy to help at first, but the more he helped, the more the requests came in, until eventually he concluded that he was spending too much of his free time with other peoples’ families instead of his own. Guilt-ridden, he started turning off his phone when he was at home or making excuses.

So people started calling Abdul to try to get in touch with Ally, but instead of turning them over to his cousin, Abdul volunteered to handle the tasks himself.

“He filled my job of helping people,” Ally said. “So they all call him every day, every day, and people leave me alone because Abdul is always ready to help.”

By then, Abdul had his own car, a used Chevy sedan nearly two decades old. Then, in spring 2022, he upgraded his ride, signing a lease on a brand-new red Toyota SUV that he decorated with flame decals on the doors.

Though he usually rocked athleisure sweats and Air Jordans, on the day he got his car, he put on a charcoal suit and white loafers.

“I have a new car, now I have to wear a suit,” Ally remembered his cousin telling him with a grin.

Beaming proudly, Abdul posed for photos in front of the car and revved the engine for his friends cheering on the sidewalk.

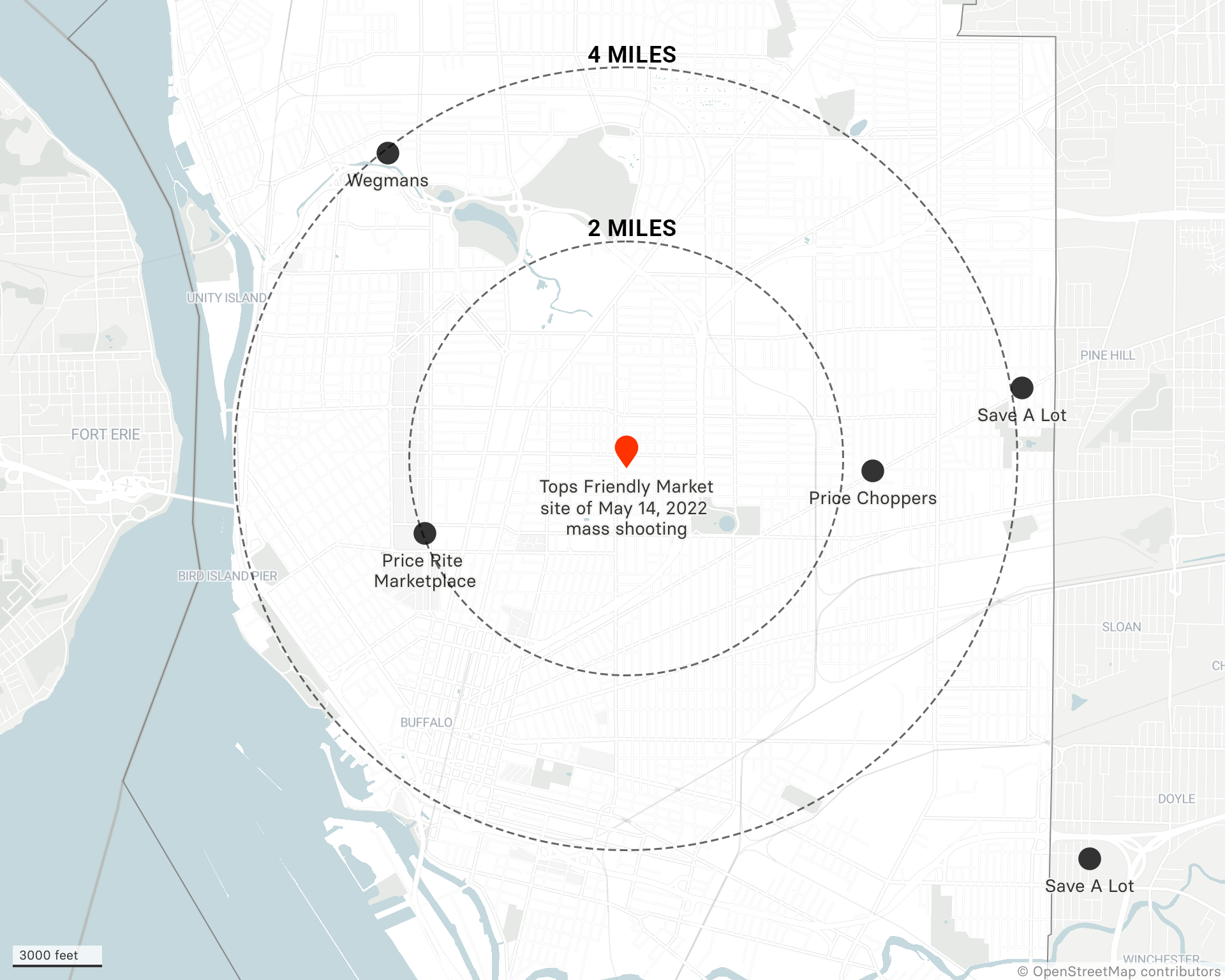

Anyone who called Abdul for help would see the red SUV pull up within minutes. Most often, the requests came from older folks who needed groceries. While there are a few corner stores in the neighborhood, the nearest supermarket, Tops Friendly Markets, is 2.5 miles away. Abdul became a regular presence at the store, a one-man transportation service with a trunk full of food.

It was only a matter of chance that Abdul was not at the Tops supermarket on May 14, 2022, when a white supremacist killed 10 people with an assault rifle. The shooter, who would be sentenced to life in prison, had driven 200 miles to target a location in a predominantly Black neighborhood. “When we heard the news,” Ally said, “we just say thank you to God we were not there.”

Following the massacre, the supermarket shut down for three months, forcing its regular customers to travel even further to buy food. The tragic spotlight on Tops drew national attention to the absence of grocery stores across the East Side, but that fact had been a prominent concern to locals for decades. Tops had opened in 2003 thanks to $3 million in public funding that came only after years of community activists calling on the city to bring a supermarket to the area.

The East Side had once boasted a flourishing bounty of commerce. After World War II, Black families who were part of the Great Migration made their way into Buffalo for jobs at its plentiful factories and booming steel plants, working side by side with the descendents of Polish and Italian immigrants who mostly lived in the southern part of town. The most affluent families lived in the city’s northern suburbs. The East Side, which spans from downtown’s Main Street to the railyard at the city’s edge, was redlined for Black residents. As in many segregated American cities in the mid-20th century, the Black community in Buffalo developed its own self-sustaining economic ecosystem, flush with supermarkets, banks, restaurants, florists, bars, jazz clubs, and clothing shops.

As plants shut down in the 1970s and ’80s, longtime steelworkers who’d earned around $30 an hour settled into minimum wage jobs at less than $6 an hour. The economic damage rippled across the city but hit the neighborhoods with the least to spare hardest. Businesses across the East Side shut down. Supermarket chains like Acme Markets, A&P, Super Duper, and Bells closed their doors. By the time the Sharifu cousins arrived on the East Side, boarded-up brick buildings and empty lots outnumbered the open storefronts around them, and shuttered factories loomed over the horizon. Today, a third of Buffalo’s residents live in poverty, the third highest rate among the country’s major metropolitan areas.

In recent years, under the administration of mayor Byron Brown, who took office in 2006, the city has aimed to resurrect its economy through development projects centered on creating jobs in the medical and education fields. New hospital and university facilities have sprouted up around downtown, luring new residents. But the influx of middle-income arrivals has led to rising rents in Buffalo. Apartments that had rented for $500 less than a decade ago have tripled in cost. As in many cities seeking to balance the benefits of urban development with the gentrification it tends to yield, an undercurrent of mistrust simmers among longtime Buffalo residents, rooted in the question of who benefits from the city’s supposed renaissance and who gets left out.

Today, a third of Buffalo’s residents live in poverty, the third highest rate among the country’s major metropolitan areas.

“I don’t know if it’s for us,” Sparkle Eubanks, a teacher’s assistant who lives on the East Side, said of the city’s new developments. “Before Buffalo started having all the outsiders come in, we didn’t have anything.”

The absence of government services has left many residents reliant on informal support systems. Often, the upwardly mobile members of marginalized communities become critical pillars in lifting up those who feel left behind.

Ben Caudle, an 81-year-old entrepreneur who has owned a bar, two laundromats, a taxi stand, a snow plow business, an auto body shop, and a salvage yard, said that over the years he has loaned thousands of dollars to East Side residents facing eviction and small business owners facing financial ruin. Caudle, who opened his first business in 1963 with money he saved from his seven years working at a General Motors plant, now runs a flea market in a building that years ago housed a supermarket. Aiming to give local merchants a place to sell their wares, he rents out the space to more than a dozen vendors who sell clothes, furniture, Buffalo Bills bedding, shoes, bags, and a wide range of knick-knacks. Sometimes, when times are tough, as it has been during the pandemic, he lets them stay at the market even when they can’t pay rent.

Louise Sano, who was born in Rwanda and went to school in Namibia, runs a clothing shop on a street where more than a dozen immigrant-owned businesses have filled blocks long riddled with vacant storefronts. She serves as a de facto lender in her community, giving out money that doesn’t always get paid back.

“I came with a suitcase and now I have a whole village,” said Sano, who arrived in Buffalo in 2007 after her husband’s sister had landed there through a refugee resettlement program.

Last year, she said, a new landlord took over her building and doubled her rent. “I told him, ‘I survived COVID, but I don’t know if I’ll survive you,’” she said. But even as her rent rises, she has refrained from increasing prices in her store.

One recent morning, one of her regular customers, Jeffrey Moore, came in to purchase several neckties with colorful prints. Moore didn’t hide his intentions: He was buying the ties for his wife, who operates a vendor table at Caudle’s East Side flea market, where she resells them for a profit. Sano supports the arrangement.

“The bread is big enough for everybody to get a bit,” said Sano. “Everybody should be able to eat.”

Before opening her own storefront, Sano had initially launched her business in 2010 through an incubator program organized by WEDI, a local nonprofit, which provides new entrepreneurs a space to operate at the West Side Bazaar, a global marketplace with vendors from Peru, Ethiopia, Myanmar, Palestine, South Sudan, and elsewhere.

The bazaar “became a symbol of cultural diversity and hope and equity,” said WEDI’s executive director Carolynn Welch. “When you walk in, you find people from all different paths of life together, getting along, eager to learn about everybody, all in this tiny little area together.”

In September, the West Side Bazaar burned down in an electrical fire, destroying the inventories of all its vendors. The bazaar has been closed while WEDI’s organizers pursue a new space for it. But “some vendors are too traumatized to restart,” Welch said.

The heavy reliance on nonprofit programs and personal generosity means that the precarious patchwork of support systems stretches thin, subject to the inconsistencies of goodwill.

“We’re made to feel like there’s not enough,” said Kelly Camacho, who grew up on the East Side and works as an organizer for the local advocacy group Citizen Action. “If this group is getting resources, where are mine? We’re being set up to be fighting for these resources.”

“The bread is big enough for everybody to get a bit.”

During the early months of the pandemic, as mutual aid programs popped up across the country, a group of Buffalo residents started a community fridge network to serve residents struggling to access food. Eventually, seven fridges went up across the city, their power cords plugged into outlets at local businesses and households. The program is run by around 20 volunteers who stock fridges with fresh produce and prepackaged meals donated by locals and restaurants, said Lauren Knowstro, one of the unpaid organizers. So many people turned to the program that volunteers had to restock the supply every day, at a cost of around $150 per fridge.

But by the end of the pandemic’s second year, she said, funding was drying up and volunteers were burning out. “We were so low on donations,” she said. The organizers wondered if they’d be able to keep the program going for much longer.

Then the Tops shooting illuminated the problem of food scarcity on Buffalo’s East Side, and a new wave of donations poured in from around the world, enough to sustain the program for at least another year. But the attention was short-lived. A month after the Buffalo massacre, a school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, burst into the news cycle, and the impact on the fridge network was immediate.

“We saw a steep decline after Uvalde,” said Knowstro, who grew up in Buffalo. “There’s no finger-pointing. It’s just humanity. There’s an influx of support after a tragedy, and then you’re onto the next tragedy. People get compassion fatigue.”

When Tops closed, more people relied on the fridges. During the supermarket’s hiatus, volunteers were restocking them two or three times a day, reflecting the absence of nearby alternatives. While areas without access to fresh food are often called “food deserts,” Knowstro said she prefers the term “food apartheid” because “desert implies the lack of availability is because of geography rather than systemic inequality.”

Now that almost a year has passed since the surge of donations, the community fridge network again faces concerns about its future.

“Creating more community fridges — is that a sustainable path forward?” Knowstro said. “Or do we need the administration to create more grocery stores? We’re a Band-Aid. After the Tops shooting, there was this rush to help. Everybody wanted to help. But nothing changed for the community.”

“After the Tops shooting, there was this rush to help. Everybody wanted to help. But nothing changed for the community.”

No new supermarkets broke ground. No government food programs emerged. No grocery delivery service for low-income residents swept in. The old disparities remained. And when Tops reopened in July, Abdul Sharifu was back prowling its aisles, pushing a shopping cart flush with goods that would end up in somebody else’s kitchen.

Abdul knew he couldn’t do this forever, Ally said. In the summer, Abdul married Gloria, a woman he had known since his days in Burundi, and they moved into their own place down the block while another newly arriving Congolese immigrant filled his old bed in the other house. By the start of winter, Gloria was eight months pregnant with their first child. Recognizing that the needs of his family would occupy him once their child was born, Abdul began contemplating who he would appoint as his successor to serve the people who turned to him for help.

Government officials warned that the blizzard coming on Dec. 23 would be severe, with winds more than 70 miles per hour and more than 4 feet of snowfall. In a press conference the day before the storm, they advised residents to stock up on food, water, and other essentials.

But many on the East Side living paycheck-to-paycheck lacked the funds for unforeseen expenses. Some without a car couldn’t quickly make it to the store and back in the window before the storm hit.

The night before the storm, Ally called Abdul to tell him to reach out if he or Gloria needed anything. Abdul called Ally the following morning to check in, letting him know that he was doing well and prepared to ride out the blizzard. The storm worsened throughout the afternoon. By evening, roads were impassable and the fierce wind and rising snowbanks made it nearly impossible to walk more than a few steps outside.

The next day, around 2 p.m. on Christmas Eve, Gloria called Ally to inform him that Abdul had left to get somebody milk two hours earlier and still hadn’t returned. Calls to his phone went straight to voicemail. Ally called friends around the city, wondering if maybe Abdul had gotten stranded somewhere and ended up taking refuge at their place.

Ally went to bed that night trying to calm the anxiety in his stomach. He held out hope that Abdul had made his way to somebody’s house; Abdul had friends all over town. On Christmas morning, he filed a missing person’s report to the police, posted a message on Facebook with Abdul’s photo, and called hospitals to ask if they’d admitted his cousin. He gathered a group of friends to look for Abdul. Then he made his way through the snow. Unsure which direction to walk, he headed west. He checked corner stores, restaurants, and the nearest supermarket.

After hours of aimless searching, he spotted a red vehicle draped in snow beside a train station half a mile from Tops. As he approached, he could tell from the flame decals that it was his cousin’s car. But when he reached it, he found it empty. He noticed that its windshield wipers had been raised, peeking above the thick layer of snow. It occurred to him that even in the frantic moments when Abdul decided to abandon his car, he’d had the presence of mind to prevent his wipers from being damaged by the snow piling on the windshield.

Ally searched the train station, thinking it might have offered a pocket of shelter amid the storm. He knocked on doors in the surrounding blocks. As night fell, he returned home, trying to ward off the rising dread.

That night, he slept fitfully. “I swear to God, Abdul was in my dream,” he said.

“Bro, are you crazy? You went outside?” he said to his cousin in the dream.

“No problem, my brother,” Abdul replied. “Chill. I’m good.”

The next day, a man who saw the Facebook post called Ally to inform him that he had found somebody who resembled Abdul lying in the street on Christmas Eve, unconscious but still breathing, and had driven him to the hospital. Ally rushed over, but when he arrived, the medical staff led him downstairs. Confusion took over. “Why are we going to the basement?” he remembered thinking. “I will always remember how cold it was down there.”

The reality only hit him when he saw his cousin’s body.

“I was sick,” Ally said.

He broke down. A panic attack followed the sobs.

“For so long it was just me and him,” he said. “After that, I feel like I’m by myself.”

Two weeks later, Abdul’s wife gave birth to their son.

Of the 31 Buffalo residents who died in the blizzard, 20 were Black — in a city where Black people make up around a third of the population. Some, like 57-year-old Loretta Andrews, 74-year-old Edward Parson Jr., and 93-year-old Doris Williams, died in their homes after power outages shut off their heat. Some, like 22-year-old nurse Anndel Taylor, died trapped in their cars on their way home from work. Some, like Abdul, died while trying to walk to safety.

The tragedy underscored inequities that continue to grip the city. Rita Jones, who grew up on Buffalo’s East Side and manages Caudle’s flea market, said the area’s residents have complained for years that the city often neglects to pour snow-melting salt on most of the roads in their neighborhoods, as it does in more affluent and commercial districts. City officials issue blizzard warnings but otherwise leave residents to fend for themselves. Those without fully stocked pantries are more likely to brave the conditions to obtain supplies. Those unable to take time off work have less time to prepare before a storm hits.

But resilience is exhausting when repeatedly called upon — a trait honed out of necessity, foisted upon those with no choice but to navigate scarcity.

Because of the city’s reputation for harsh winters and its lore of producing hard-scrabble steelworkers toughened by mills that filled their lungs with asbestos and carcinogenic fumes, outsiders’ perception of Buffalo is usually framed by an admiration for its peoples’ resilience. But resilience is exhausting when repeatedly called upon — a trait honed out of necessity, foisted upon those with no choice but to navigate scarcity.

People turned to Abdul Sharifu because they had nobody else to turn to, and he provided services that nobody else would provide. His death brought pain to those who loved him, but also left a vacuum for those who needed him.

When he misses his cousin most, Ally scrolls through his phone to look at pictures and videos of their happiest moments. Abdul in a yellow shirt, orange camo sweatpants, and white Jordan IVs, posing on the porch with friends — always the most stylish among them. Abdul in a shiny red suit and Nike slides the day before his wedding, entertaining guests with jovial antics each time one presented him with a gift, kneeling down so they could try to balance the wrapped boxes on his head.

“This guy, all the time was joking,” Ally said.

After Abdul’s death, Gloria moved to Syracuse, where her brother, sister, and mother live. She told Ally that she couldn’t bear to live in the house she shared with Abdul and needed a fresh start, he said.

Ally started a GoFundMe to help cover his cousin’s funeral costs and support Gloria and their child. More than $64,000 flowed in, including an outpouring of small donations from people with little to spare — a testament, he said, to all the lives Abdul had touched. Part of the money went toward paying off Abdul’s red Toyota SUV, which had $10,000 left on the lease. Ally installed a baby seat in the back.

“It was important that we were able to buy the car,” Ally said. “Now Abdul has something to pass down to his son.” ●