MOULTRIE, Georgia — “All you black American people, fuck you all...just go to the office and pick up your check,” the supervisor at Hamilton Growers told workers during a mass layoff in June 2009.

The following season, according to a lawsuit filed by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, about 80 workers, many of them black, were simply told: “All you Americans are fired.”

Year after year, Hamilton Growers, which has supplied squash, cucumbers, and other produce to Wal-Mart and the Green Giant brand, hired scores of Americans, only to cast off many of them within weeks, according to the U.S. government. And time after time, the grower filled the jobs with foreign guest workers instead.

Although Hamilton Growers eventually agreed to pay half a million dollars to settle the suit, company officials said the allegations are baseless. Mass firings never happened, they said, nor did anyone use racially inflammatory language. But workers tell a different story.

“We want to go to work and work all day,” said Derrick Green, 32, a father of six who said he was fired by Hamilton Growers in 2012 after only three weeks picking squash. “But they don’t want that.”

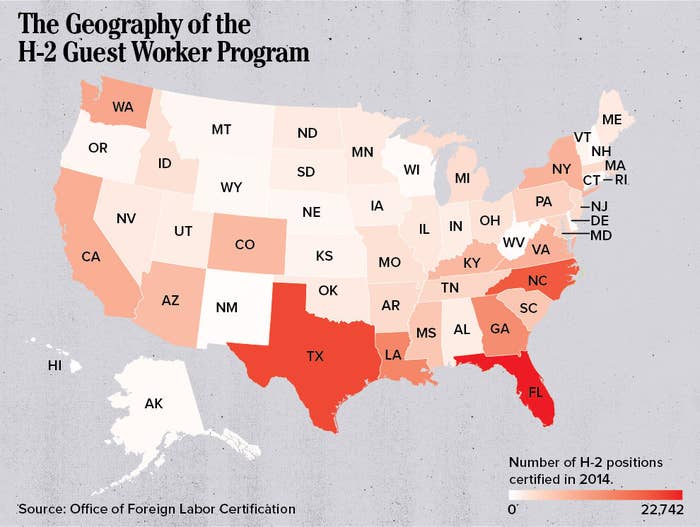

Last year, thousands of American companies won permission to bring a total of more than 150,000 people into the country as legal guest workers for unskilled jobs, under a federal program that grants them temporary work permits known as H-2 visas. Officially, the guest workers were invited here to fill positions no Americans want: The program is not supposed to deprive any American of a job, and before a company wins approval for a single H-2 visa, it must attest that it has already made every effort to hire domestically. Many companies abide by the law and make good-faith efforts to employ Americans.

Yet a BuzzFeed News investigation, based on Labor Department records, court filings, more than 100 interviews, inspector general reports, and analyses of state and federal data, has found that many businesses go to extraordinary lengths to skirt the law, deliberately denying jobs to American workers so they can hire foreign workers on H-2 visas instead.

A previous BuzzFeed News report found that many of those foreign workers suffer a nightmare of abuse, deprived of their fair pay, imprisoned, starved, beaten, sexually assaulted, or threatened with deportation if they dare complain.

At the same time, companies across the country in a variety of industries have made it all but impossible for U.S. workers to learn about job openings that they are supposed to be given first crack at. When workers do find out, they are discouraged from applying. And if, against all odds, Americans actually get hired, they often are treated worse and paid less than foreign workers doing the same job, in order to drive the Americans to quit. Sometimes, as the government alleged happened at Hamilton Growers, employers comply with regulations by hiring Americans only to fire them en masse and hand over the work to foreign workers with H-2 visas.

What’s more, companies often do this with the complicity of government officials, records show. State and federal authorities have allowed companies to violate the spirit — and often the letter — of the law with bogus recruitment efforts that are clearly designed to keep Americans off the payroll. And when regulators are alerted to potential problems, the response is often ineffectual.

Officials at the U.S. Department of Labor, which is charged with protecting workers and vetting employers seeking visas, said in a statement: “We acknowledge that the laws that authorize these programs are inadequate.” But the department also said that despite limited resources, it “actively pursues measures to strengthen protections for foreign and U.S. workers.”

The H-2 visa was created to address shortages in the American workforce. Although labor is indeed tight in some areas — such as North Dakota, where an oil boom has driven unemployment below 3% — there is little evidence of labor shortages in many industries that use the visas. In some cases, there is even a glut of available workers.

Landscaping companies, for example, were approved for more than 30,000 H-2 visas in the 2014 fiscal year. Yet Daniel Costa, a researcher at the Economic Policy Institute, which receives some funding from unions, found that over the same period, unemployment in landscaping was more than twice as high as the national average.

“The problem with the system is that the H-2 workers who are coming in are not tied to actual, demonstrated labor shortages,” Costa said.

Companies that have difficulty finding American workers could attract more applicants by offering higher wages. But instead of encouraging or even subsidizing that, the government’s H-2 program effectively subsidizes the opposite effort — helping companies find pliant foreign labor, often at the expense of American workers.

In the last five years, the number of H-2 visas issued by the State Department, which administers the program along with the Department of Homeland Security and the Labor Department, has surged by more than 50%.

Bills in Congress to expand the guest worker program have won support from both Democrats and Republicans in recent years. Business groups such as the Chamber of Commerce have lobbied for as many as 400,000 additional H-2 visas per year. But the issue has been overshadowed by larger debates over the legal status of millions of undocumented immigrants.

Around the country, lawyers and labor brokers actively promote the H-2 program as a way to boost profit margins. Usafarmlabor, a labor broker serving the agricultural industry, until this month bluntly stated on its site: "Our workers actually save you money each month in a comparison with U.S. workers.”

Employers who use the H-2 program note that it entails numerous added costs, including visa fees and transportation, as well as compliance with complex rules. It requires that most workers be paid above minimum wage, sometimes substantially so.

But the guest worker program also offers numerous financial incentives. Agricultural employers are exempt from payroll and unemployment taxes on H-2 workers, for example; nonagricultural employers do not have to provide housing, but if they do they are allowed to charge their workers rent, which is sometimes extortionate.

Foreign laborers usually live at the job site, available to work at any time. They typically come alone, without families or other distractions that could cause them to miss work. The terms of their visas prohibit them from taking other jobs, so they have almost no leverage when it comes to wages or working conditions. And since they often come from abject poverty in their home countries, many visa holders put up with difficult or even backbreaking conditions without complaint to ensure they are invited to return the next year.

The visa program can be even more advantageous to the many employers that exploit their guest workers, making them work long hours without overtime pay, charging them illegal fees, or flat-out cheating them of their wages — all of which are against the law, regardless of whether workers are American or foreign.

Hamilton Growers has been cited, repeatedly, for its treatment of its mostly Mexican workforce. Even as the farm was accused of casting off American workers, government investigators found that it failed to pay foreign employees all they were owed and that it housed them in often deplorable conditions. Hamilton Growers vigorously denies that it mistreated workers.

Americans are far less isolated than foreigners on H-2 visas, many of whom cannot speak a word of English. U.S. workers often know at least some of their rights and how to complain about abuses. They frequently have family nearby whom they can turn to for support. And, perhaps most importantly, they can’t be threatened with deportation. But the guest worker program can still have a devastating impact on their jobs, their families, and their entire communities.

In house after house in Moultrie, American workers said they have been shut out of agriculture jobs that have been available in their community for generations. Older workers talked of becoming impoverished; younger ones said their chances of financial stability have been strangled, leaving them, in some cases, with little choice but to leave town.

“They got rid of us,” said Mary Jo Fuller, referring to black workers. A field-worker on and off for most of her life, she said she was abruptly terminated from J&R Baker Farms, near Moultrie, as part of a mass firing in 2010. Unable to find other employment, the 59-year-old said she wound up homeless for more than a year. “We don’t really have jobs no more.”

Moultrie is “nowhere, really, for a young person trying to make it,” added Green. “It just makes you angry, very angry,” he said. “We right here in America, and you don’t want us to work. You’d rather get foreigners.”

For several years, Abrorkhodja Askarkhodjaev ran a temp firm based in Kansas City that relied on H-2 guest workers from the Philippines, Jamaica, and the Dominican Republic and that serviced large hotels and other businesses around the country.

“Foreign people will clean two rooms in one hour. The American will not even finish in one hour one room,” he said speaking from the federal prison where he is serving a 12-year term for crimes related to visa fraud.

“Foreigners are better,” Askarkhodjaev added. “Of course I tried not to hire Americans.”

Before a company can bring in any guest workers, it must clear a series of legal hurdles to prove to the government that it has tried but failed to recruit Americans for the job.

Companies that don’t actually want Americans, however, have devised a whole set of creative tricks to get around these hurdles.

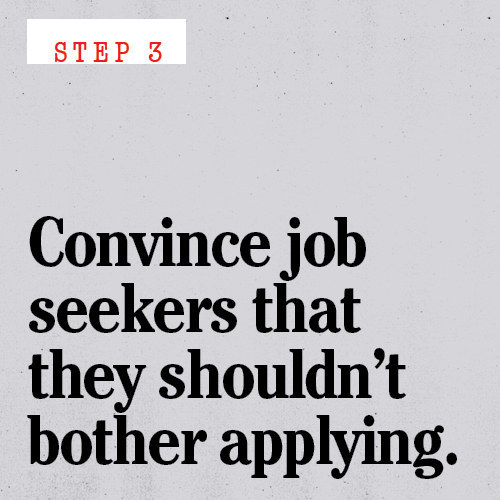

To apply for the right to import foreign workers, a company must first post at least two newspaper job ads, including one on a Sunday, “in the area of intended employment.”

Some employers have a very broad definition of “area of intended employment.”

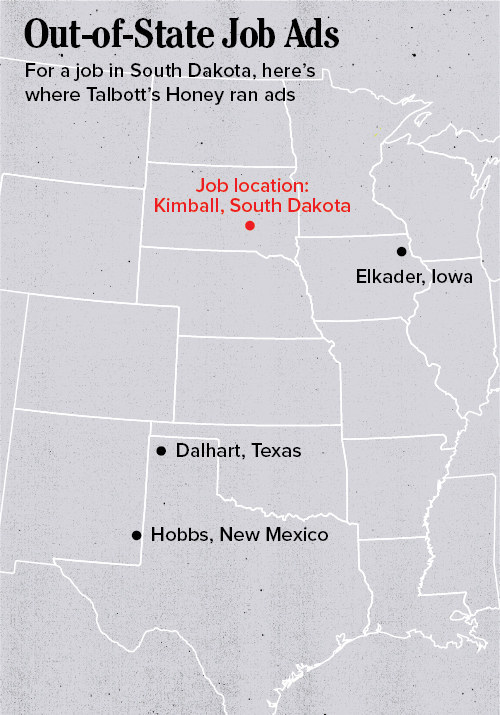

In January 2011, Talbott’s Honey, a small honey producer, placed ads as required soliciting workers for jobs in Kimball, South Dakota. The ads, however, ran in Elkader, Iowa; Dalhart, Texas; and Hobbs, New Mexico — towns that are hundreds of miles from Kimball.

Talbott’s then told the government there were no available American workers and got permission to import 12 foreign workers instead.

Reached by phone, the company declined to comment on the matter. But when asked why it hadn’t run an ad somewhere in the actual vicinity of the job, Talbott’s wrote that it had tried but the ad “somehow fell thru the cracks,” according to Labor Department records.

Sometimes the government actually abets this tactic. In North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, seasonal jobs cutting down Christmas trees in the frenzied weeks before the holiday pay well. But year after year, the state’s online job board has incorrectly posted those jobs in the wrong counties, sometimes hundreds of miles from any pine forests. As a result, workers looking for Christmas tree work close to home face a peculiar paradox: The only way to find the openings nearby is to search in a faraway corner of the state.

Lawyers at Legal Aid of North Carolina have been complaining to the state Department of Commerce about the Christmas tree job posting discrepancies for years. Yet despite repeated promises by state regulators to fix it, the issue persists, the lawyers said.

Indeed, officials in the state at times seem to make it easy for employers to avoid hiring Americans. During the fiscal year that ended this July, the state’s job bank tallied work orders seeking H-2 workers for 17,496 agricultural job openings, according to the North Carolina Department of Commerce. More than 7,000 U.S. farmworkers had registered with the agency actively seeking work — yet only 505 of them were referred to those jobs.

Kim Genardo, spokesperson for the department, wrote in an email that the state’s “Foreign Labor Certification program is absolutely in compliance with federal law.”

Across the country, employers have run ads that failed to list any contact information, omitted the name of the company, or excluded relevant information such as what kind of job it was, where it was located, or how much it would pay, records show.

Some simply don’t place ads at all.

For years, Linda White ran a business in Livingston, Louisiana, securing H-2 visas for hundreds of employers. Late last month, she was sentenced to 18 months in federal prison for creating phony receipts in an attempt to convince regulators she had placed newspaper ads for dozens of clients, when in fact she had not. During a three-year period reviewed by the Labor Department, her clients were approved for more than 8,000 visas, federal data shows.

In an interview, White called the matter “a mistake,” adding that “nobody was going to call for these jobs over dumb newspaper ads anyhow. When clients come to me, what they want is their Mexicans.”

The H-2 program dates all the way back to 1952, and employers have been coming up with ways to game the system for almost as long.

An information sheet from the Snake River Farmers Association in Idaho from the mid-1980s, obtained by a legal aid group representing farmworkers from Texas, offered a list of tips on how to write job postings so that they would deter American applicants.

"Irrigators or pipe movers is a great job description because no one wants to move pipe,” the fact sheet said. “Ranch Hands,” by contrast, is “a poor description,” the memo noted, adding: “One might get some adventuresome young ladies from Cincinnati seeking the thrill of working on a western ranch. With numerous applications from such U.S. workers, the employer would never get around to recruiting aliens."

In response to a query from BuzzFeed News, Jeanne Malitz, a lawyer who represents the association, initially said it was “unaware of the source of this document, or whether it was published or ever disseminated” and disavowed its contents. Told of the document's origin, she declined to comment further.

Despite all the obstacles, some U.S. workers do manage to find out about job openings at the companies that are seeking to hire abroad. But many of those companies set unusually stringent requirements — for their U.S. applicants, at least.

Even for entry-level jobs, or tasks as simple as picking melons, some employers demand that American applicants have months or sometimes even years of experience, clean drug tests, high school diplomas, familiarity with botanical nomenclature, knowledge of diabetic cooking, multiple references, or commercial driver's permits.

Despite the H-2 program’s focus on unskilled labor, employers seeking guest workers routinely demand previous work experience, further raising the bar for Americans. In recent years a full three-quarters of companies approved to bring in agricultural guest workers have listed such requirements, according to a BuzzFeed News analysis of federal data. In some states — as geographically diverse as New York, North Carolina, Montana, and Washington — virtually all agricultural employers demand prior experience.

Such requirements are a way to “filter out U.S. workers,” said Lori Johnson, an attorney at Legal Aid of North Carolina. She noted that some fruit and vegetable picking jobs now require three months of experience. And, Johnson said, there is little evidence that such requirements are ever imposed on the foreign guest workers who ultimately get the jobs.

Some requirements also appear racially coded.

“I will keep my pants pulled up around my waist. I will wear pants and shirts that fit,” reads a document that Hamilton Growers required its workers to sign in 2013. “If I have long hair or extensions in my hair, I will fix my hair in such a manner that it can be placed under a hair net.”

Jon Schwalls, director of operations at the farm, said it was “ridiculous” to suggest that the language targeted black workers; those rules were about food and workplace safety, he said.

Early this year, the sign manufacturer Persona, of Watertown, South Dakota, obliged American applicants to take the Thurstone Test of Mental Alertness, which “helps measure an individual’s ability to learn new skills quickly, adjust to new situations, understand complex or subtle relationships, and be flexible in thinking.”

The 20-minute exam is often deployed to assess computer programmers, accountants, bank managers, and commercial airline pilots, but Persona used it to evaluate — and reject — Americans applying for painting and welding jobs. A Labor Department official questioned whether the test “is going to be administered to foreign workers.”

A Persona official declined to comment.

When American workers showed up to apply for a job at Pro Landscape, in Hillsboro, Oregon, they were told they would have to dig a trench four feet long, a foot and a half wide, and a foot and a half deep within five minutes to be considered for the position, according to Labor Department records.

Manuel Castaneda, the company’s owner, called the task a “fair way” to see who was up to the job. But the Labor Department said the tests appeared “to not be normal” for the industry and to “be restrictive to U.S. workers.” Indeed, Labor Department records show that only five of the 18 applicants who attempted the tests passed. “The employer’s tests,” the department found, appear to have “discouraged U.S. workers.”

When Nicole Burt applied for work as a stable attendant in Kentucky, she was sure her experience and skills were unimpeachable. As a teenager in Vermont she showed, trained, and groomed horses, and no sooner did she graduate high school than she moved to the Bluegrass State in order to be in what she dubbed “the horse capital of the world.”

In early 2011, she applied to a dozen or so stables, she said, but none called her back. One of them was Three Chimneys Farm, a stately home for legendary thoroughbreds including the 1977 Triple Crown winner, Seattle Slew.

Three Chimneys, based in the town of Versailles, had told federal authorities it was “facing a distinct labor crisis and cannot locate or retain American workers” and that “all U.S. workers who express an interest in the employment opportunity will be interviewed for employment.” But when Burt called to check on her application, she was told no jobs were available.

“Basically we never hire US workers who are applying,” the farm’s director of human resources, LaTerri Williams, told the Department of Labor in a signed statement. “I don’t conduct interviews or take their applications. Basically I just tell them we have no openings.”

Asked by regulators why it didn’t give Burt a chance, as federal law required, the company stated that the single mother of three was better off unemployed than taking the $9.71-an-hour job. “Given the length of the commute, the cost of daycare, the loss of her eligibility for food stamps, it would cost Ms. Burt more to work for Three Chimneys than if she did not work at all,” the company said.

Burt said she never found another job working with horses, and in the months she waited, holding out hope that she’d get a call, she lost both her cars and her house. Almost four years later, the Labor Department awarded her $16,313 — the amount regulators calculated she would have earned at Three Chimneys had she been hired as the law required.

Three Chimneys did not respond to several requests for comment.

“I kept hearing the employers say that they couldn’t find anybody. And I just want to smack them, because we’re right here,” said Burt. “I felt betrayed. I just felt like America had let Americans down.”

The Westin Kierland Resort & Spa in Scottsdale, Arizona, was approved for 23 foreign housekeepers in 2012, arguing that the golf and convention seasons created a need from October to May. As required by law, the sprawling luxury resort, part of the $12 billion Starwood chain, placed ads for American workers in the Arizona Republic newspaper — but it rejected all five applicants. The company told the Labor Department that some failed to meet a one-month experience requirement.

The following year, however, when government inspectors contacted some of those rejected workers, a different story emerged. One applicant “revealed that she had over 25 years of housekeeping experience” and “used to run her own motel in Colorado,” investigation documents said.

The Labor Department ultimately ordered the Westin Kierland, which has a championship golf course, multiple pools, and a 900-foot “lazy river” spread over 262 acres, to pay a total of $13,500 in lost wages to two American workers it judged should have been hired. In a statement, Bruce Lange, Westin Kierland's managing director, said the resort disagreed with the Labor Department’s findings but “chose to resolve the matter in order to focus our time and resources on caring for our associates and guests.”

Throughout the Midwest, corn detasseling is a popular summertime gig. So when D&K Harvesting filed a job posting in April 2013 — a step it had to take to win approval to import 120 H-2 workers — Katlyn Sanchez rushed to apply. The job, which involves removing the flower from cornstalks, typically draws high school kids and young adults.

But when the Kalamazoo, Michigan, teenager’s mother spoke to a recruiter over the phone a few days later, she was warned that it was “not a good situation for a young female worker alone,” according to a complaint later filed to regulators by Sanchez. “There will be all single men from Mexico” working alongside her, the recruiter later said, and her daughter “could get physically or sexually attacked.”

The recruiter added that D&K “will not be responsible for anything that happens” to Sanchez in the fields. Employers do not have the right to absolve themselves of workplace dangers, nor to decide that they'd rather not hire women. But the recruiter’s tactic worked: Sanchez’s mother agreed not to let her take the job.

The recruiter offered her approval: “I think you’ve made a good choice.”

D&K president Larry Marsh did not return several calls seeking comment.

Far off the interstate, perched under a big blue sky and surrounded by fields of fluffy cotton, Moultrie, population 14,000, feels frozen in time. Coffee can be found for less than a dollar. The charming central square is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. And the town's quiet old neighborhoods — some graceful, some ragged — are deeply segregated.

For many black men, job options are especially scarce. In the spring of 2012, Derrick Green, the father of six, had been unemployed and looking for work for several months, while his wife’s uncle, Derek Davis, 42, had trouble landing a job because of a pair of old drug convictions. When the two friends went together to the Moultrie branch of the Georgia Department of Labor to review job listings, both said they were desperate for work.

They were referred to Hamilton Growers, one of the area’s largest farms and one of the county’s largest employers, which had posted the openings as part of three separate applications to import a total of 614 H-2 workers that year.

Along with roughly a dozen other folks, most of them black, Green and Davis submitted to drug tests and filled out applications. Picking squash under a relentless Georgia sun for $9.39 an hour is brutally hard and monotonous. But Green, who is athletic and slender, said he “learned to pick” as a child alongside his grandmother. Davis, a former U.S. Army mechanic, said he first toiled in the fields at 14.

It was June and already sweltering when they reported to work among lush crops rolling across the red clay. Rumbling old school buses transport workers to and from long rows where they stoop in the hot sun, picking squash, cucumber, and peppers.

Hamilton Growers is owned by the Hamilton family, which boasts that it has cultivated land in this area for six generations. The enterprise has grown into an agricultural behemoth, with more than half a dozen interconnected corporations and LLCs running each aspect of the business: While Hamilton Growers files H-2 visa requests to the Labor Department, Southern Valley Fruit and Vegetable sells produce grown on the land.

Beyond south Georgia, the farm also has operations in Tennessee and in 2003 went international, cultivating hundreds of acres in a remote section of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

At the headquarters in Norman Park, a 20-minute drive northeast of Moultrie, a prominent plaque proclaims that the farm commits to “feeding the nations and providing a source of income for those who labor here, as servants of our Lord for His glory.” The chief executive, Kent Hamilton, is beloved by local youths for the zip line over his swimming hole. He is on the board of the nonprofit Georgia Fruit and Vegetable Foundation and has donated thousands of dollars to local elected officials, including former U.S. Sen. Saxby Chambliss, who lives in Moultrie and previously chaired the powerful agriculture committee.

Nearly two decades ago, Hamilton Growers began bringing in foreign guest workers. It’s a transition increasing numbers of farmers have made in recent years — often, as in Hamilton’s case, after complaining they had lost crops for want of people to pick them.

“You don’t save any money” by using H-2 guest workers, said Matt Scaroni, whose family owns Fresh Harvest, a farm labor contractor based in California that accounted for roughly one-fifth of all agricultural H-2 visas approved in the state last year.

By Scaroni’s calculation, housing, transportation, and legal costs, not to mention state and federal inspections and regulations, cost upwards of $4,000 to $5,000 for each guest worker “before they pick one fruit.”

In the past year, Scaroni said, Fresh Harvest has rented entire motels in Salinas to accommodate workers, along with apartments and traditional farmworker housing. The company has also been forced into once unthinkable expenditures, such as purchasing 3,000 new beds and launching a catering operation to provide meals, he said. In Salinas, he added, a paid cleaning service even visits many of the Fresh Harvest motels.

That’s a very different standard of living from that of many guest workers at Hamilton Growers. Some of them live in concrete dorms, others in rotting old school buses on cinder blocks in a forest near the grower’s packing operation, for which they say they must pay nearly $300 a month. In 2005, health inspectors told Hamilton Growers that its portable toilets couldn’t simply “have a hole cut in the bottom and a pit dug for waste.”

On a recent afternoon, some Mexican H-2 workers sat in the thick heat inside a dimly lit school bus and said that the company wasn’t paying them for all the hours they worked. None agreed to be named. “People are scared,” one of them said.

Their grievances echo those made by more than a dozen Mexican H-2 workers who sued Hamilton Growers and Southern Valley in federal court last year, alleging that the companies had engaged in intentional wage theft. American workers eventually joined the suit.

The companies deny the charge, but earlier this month they agreed to pay $485,000 to settle the lawsuit because, Schwalls said, doing so was less expensive than litigating it.

He said that the company pays its employees properly and that its housing “meets and exceeds” federal standards. All bedrooms have central heat and air conditioning even though it is not required, he said, and there are no pit toilets at the housing site.

He expressed shock when told that workers had a receipt showing they had paid the company’s longtime foreman, who departed this summer, $296 a month to live in the school buses. “That is not our land,” Schwalls said. “I can only speak to those workers who choose company housing, which is at no charge to the employees.”

Hamilton Growers has consistently maintained that it uses foreign workers not because they are cheaper or more pliant, but because there are simply not enough U.S. workers. “I would prefer to have an all-domestic workforce,” Schwalls said. “We hire 100% of the American applications we receive.”

But according to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Hamilton Growers fired or pushed out “the overwhelming majority” of the 114 American field-workers it hired in 2009 — but “few to none” of the 370 Mexican guest workers. In 2010, the company hired 233 American workers and got rid of “nearly all” of them, yet almost none of its 518 Mexican H-2 employees lost their jobs. The story was the same in 2011, the government charged in a rare lawsuit.

In late 2012, the company agreed to pay $500,000, without admitting guilt, and entered into a consent decree, pledging to be “a model employer in the area of anti-discrimination and equal employment opportunity.”

Despite the settlement, Schwalls said the government’s claims were “completely inaccurate and false” and that it was only poor record keeping that prevented Hamilton Growers from proving that workers had voluntarily abandoned their jobs. “It’s just a family farm,” he said. “There was no understanding of the need for documentation.” Wal-Mart, which has been one of the farm's customers, declined to speak for this story, while Green Giant didn’t respond to a request to comment.

By the time Derrick Green applied for the job at Hamilton Growers in 2012, he had heard rumors about troubles at the farm but was assured by staff at the local employment office that the company had mended its ways.

“They told me they was good now,” Green recalled.

He lasted just three weeks, he said, before he and a dozen other Americans were abruptly fired for not meeting production targets.

The workers protested, demanding to see some kind of accounting of their performance, but the company refused to provide it, Green recalled. “We had a big argument in that office,” he said. The dispute ended, he said, only after one manager pulled out a can of mace and another picked up the phone to summon the cops.

Schwalls said he could not comment on terminations of individual employees but insisted no one was ever threatened with mace.

This month, as part of their settlement of the suit brought by foreign guest workers, Hamilton Growers and Southern Valley agreed to pay 13 American workers, including Green, $1,500 each for claims that they were wrongly fired.

After their time at Hamilton Growers, Green and Davis returned to the employment office and were referred to J&R Baker Farms, another big vegetable grower in the area that has come to rely heavily on guest workers. In 2012, the farm applied for 160 H-2 visas, arguing there were not enough Americans who wanted the job.

Davis and Green were both hired. For the first few days, they say, the company made it difficult for them to work — by not sending the bus that was supposed to transport them to the fields or by dismissing them after just a couple of hours. On Green's fourth day, the bus made an unscheduled stop at the front office, Green recalled, and a foreman told the Americans — but not the Mexican guest workers — to get off the bus. Nine Americans were fired that day, according to a lawsuit Green and others later filed against the company.

J&R Baker too has been repeatedly accused of mistreating both its American workers and guest workers. In 2010, the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour division fined the farm $136,500 and said it should pay $1.3 million in back wages. The farm eventually settled with the agency, agreeing to pay a fraction of those amounts.

In 2012, two dozen black workers sued J&R Baker, alleging that they were held to different production standards than H-2 workers and that many of them were unlawfully fired for not meeting quotas. The grower settled that case in February 2014, agreeing to pay up to $2,200 to each of the terminated employees.

Six months later, in a case similar to the one it filed against Hamilton Growers, the EEOC filed suit against J&R Baker in federal court, accusing the grower of giving American workers fewer hours than guest workers and then firing them.

Among the plaintiffs who received $2,200 in the 2012 case is Fuller, the woman who said she wound up homeless after being laid off. Fuller said her firing was particularly painful because of her long relationship with the Baker family. She grew up on the farm, she said, and her grandmother was a nanny for the family. She said she took care of Jerod and Rodney Baker, the two current owners, when they were kids.

Back then, she said, they were “sweet little boys.” Sitting on a rickety lawn chair in front of her tiny home in Moultrie, Fuller frowned. “They grown now. They can do what they want.” She paused. “They mean.”

In an interview, Jerod Baker said his former workers’ allegations were false. They weren’t fired, he said — they quit.

“They’ll say anything, believe me. Half of them was either on drugs or coming to work late or smelling like a brewery," he said. “They literally come out here with baggy pants, and they have to hold their pants up, and the other ones either have a cigarette in their mouth or a cell phone. How are they going to be able to work like that?” He added, “85% of them told me, 'Screw this, we’ll keep getting our government check.'”

Baker vowed never to settle the lawsuit filed by the EEOC, even though, he said, fighting it is costing him a fortune. “The word on the street is go get a job with J&R Baker or Southern Valley, work for a few days, and quit — you can go sue them and then get you a check. That's exactly what's going on.”

As for Fuller, he said the idea that she was his babysitter was “the craziest bull sense of crap I ever heard.”

The heart of the issue, Baker said, is that domestic workers “can’t keep up with the Mexican workers. It’s just a disaster,” he said. “We would much rather hire American people in our own country to work, but they will not work.” Without legal guest workers or “illegal people” to work the fields, Americans are “either going to have to buy all our food from another country, or we're going to have to all starve to death.”

The H-2 program often pits one vulnerable group against another.

Last year, the South Carolina watermelon and blueberry producer Coosaw Farms was sued in federal court by black workers who allege their bosses told them “colored people just don’t work as fast as Mexicans.” The suit charges that Coosaw officials called its American employees “niggers” and made it easier for Mexican workers to meet production quotas. The farm also gave its H-2 workers access to nicer bathrooms, letting them wash their hands before lunch, the lawsuit claims.

Angela O’Neal, who helps direct the H-2 program at the farm, said she could not comment on the litigation, which is still pending, but added, “I can say that we do not, nor would we ever, tolerate a work environment that is anything less than respectful toward each and every employee.”

She added that “independent, third-party audits” — performed on behalf of buyers — “confirm that the company has a strong record of providing a positive and fair work environment for our employees, regardless of their nationality.” She declined to provide the audits, saying, “We do not own them and do not have the legal authority to share them.” In 2013, Labor Department investigators looked into a complaint that Coosaw had displaced domestic workers in favor of guest workers but found it was unsubstantiated.

Around Moultrie, the resentment goes both ways. Inside a sweltering school bus near the Hamilton Growers labor camp, Mexican workers complained that U.S. workers don’t have to work as hard as they do, aren’t required to work on Sundays, and often get released early — apparently unaware that the American workers want more hours, not fewer.

Many American workers, meanwhile, are resentful because they claim guest workers are stealing their jobs. But some Americans note that the workers who replace them get a raw deal too.

“It ain’t hard to see. As long as they out there on that farm, they must work, and they never get to leave. I felt bad for them,” Green said.

His uncle-in-law, Davis, said he feared that the lack of jobs might eventually force him to leave his home. Standing next to a trailer he is refurbishing on a family plot of land, Davis gestured out at the lawn and the quiet country roads slicing through green fields that stretch to the horizon.

“This is my country,” he said, “and I can’t get a break for nothing.”

The Jobs No Americans Can Get

Every year, thousands of U.S. companies use special visas to bring in foreign guest workers. Many of those workers get ripped off, while the Americans who are supposed to get first crack at those jobs get nothing.