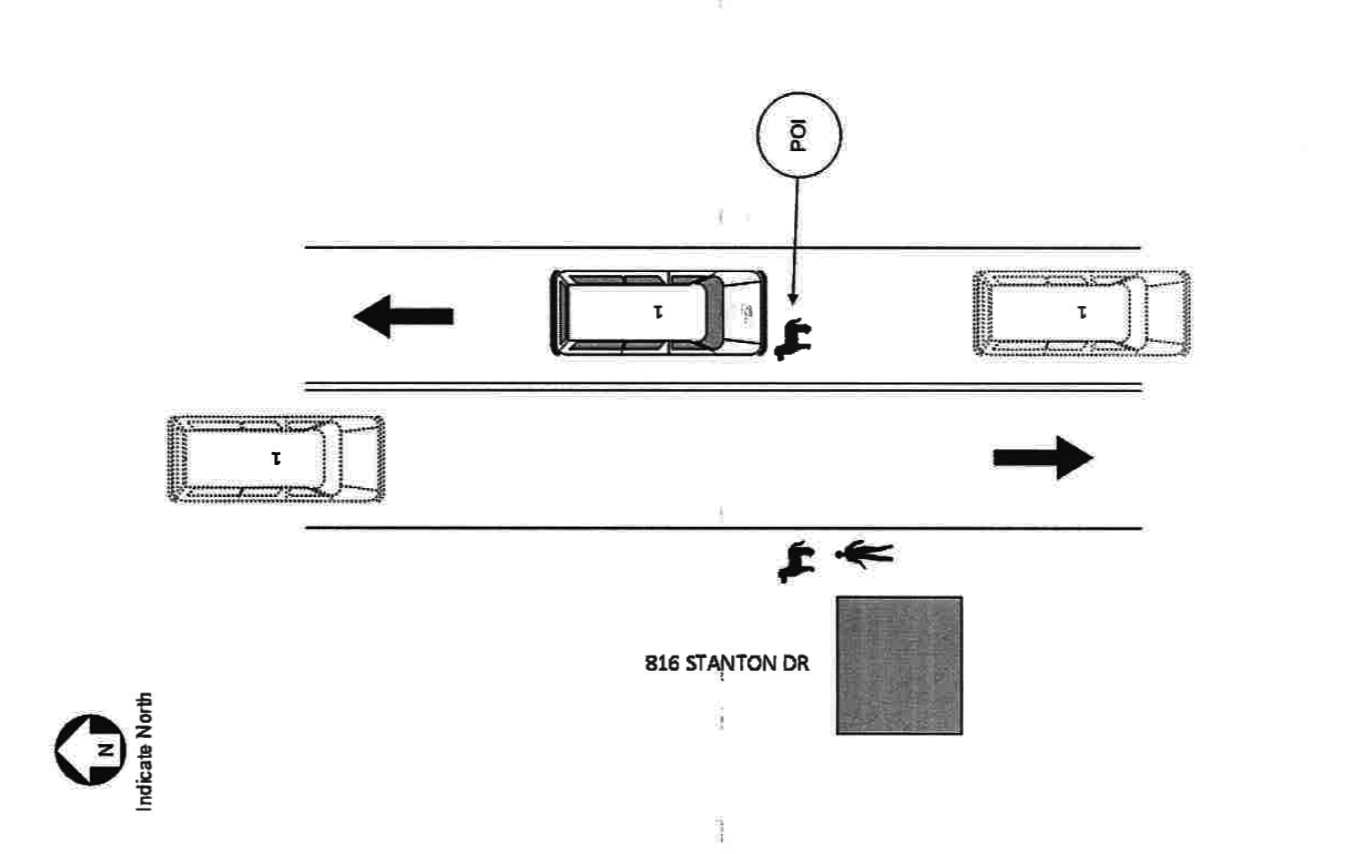

Valdimar Gray was delivering packages for Amazon at the height of the pre-Christmas rush when his three-ton van barreled into an 84-year-old grandmother, crushing her diaphragm, shattering several ribs, and fracturing her skull.

“Oh my god!” screamed Gray as he leaped out of his van. It was a bright, clear afternoon on Dec. 22, 2016, and the 29-year-old had been at the wheel of the white Nissan since early that morning, racing to drop Amazon packages on doorsteps throughout Chicago. He stood in anguish next to Telesfora Escamilla as she lay dying, her blood pooling on the pavement just three blocks from her home. After the police arrived, Gray submitted to drug and alcohol tests, which came up clean. He would later be charged with reckless homicide.

The officers who investigated the crash didn’t ask Gray about the constant pressure for speed he faced as a driver for Inpax Shipping Solutions — one of hundreds of small companies that make up Amazon’s gigantic delivery network across America. If they had, they would have discovered that the company’s drivers worked under relentless demands to deliver hundreds of packages each shift — for a flat rate of around $160 a day — at the direction of dispatchers who often compel them to skip meals, bathroom breaks, and any other form of rest, discouraging them from going home until the very last box is delivered.

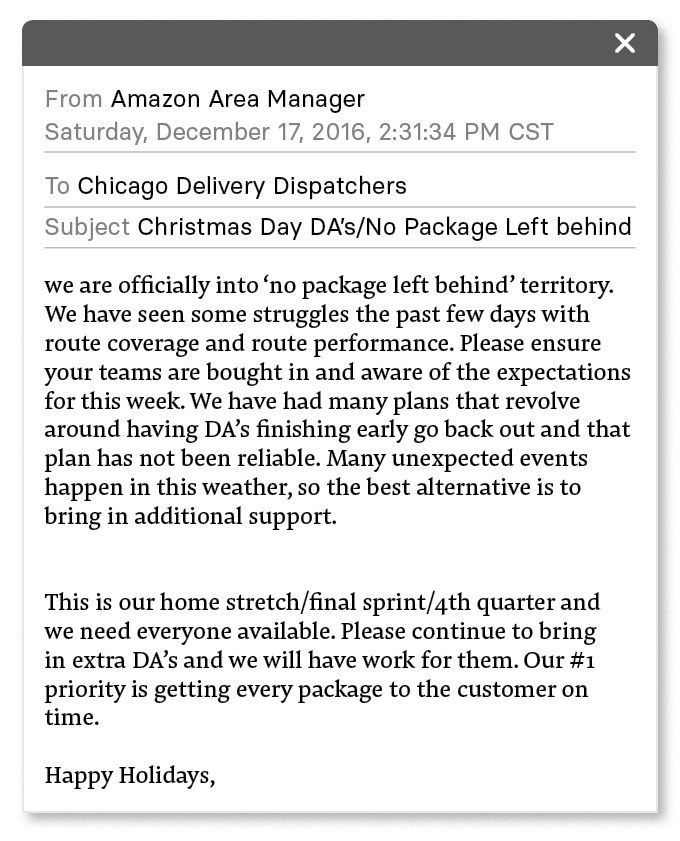

Amazon issued Inpax hand scanners that could monitor the progress of its drivers as they delivered their packages and dictated the routes they drove. It had sent Gray’s bosses at Inpax a memo just days before the accident, criticizing lackluster delivery rates in the area and instituting a “no package left behind” policy during the critical holiday week. The number of deliveries drivers were expected to make each day was way up, and dispatchers were urged to keep as many of their vans on the road for as long as possible — even if it meant driving long into the bitter winter night.

But when Escamilla’s grieving family sought redress — suing Amazon, Inpax, and Gray for wrongful death — the e-commerce giant refused to accept any responsibility. “The damages, if any, were caused, in whole or in part, by third parties not under the direction or control of Amazon.com,” its lawyers said in a court filing.

Inpax had by then been repeatedly cited by the Department of Labor for withholding pay from its drivers. Its owner had several cocaine-related felony convictions and had previously declared bankruptcy after missing insurance payments, failing to pay taxes, and defaulting on loans and other obligations amounting to $15 million. And the company was struggling to make ends meet on the razor-thin margins of a system set up by Amazon to squeeze contractors while minimizing its own costs at every turn.

Just months before Escamilla’s death, a former employee told BuzzFeed News, Inpax had stopped paying for a critical safety monitoring service it had installed in every van in Chicago — equipment some felt could have helped prevent the accident.

But despite Inpax’s checkered record, after denying any blame for Escamilla’s death, Amazon continued using the company to deliver its packages across Chicago and at least four other major cities. Inpax did not respond to a detailed written request for comment.

The super-pressurized, chaotic atmosphere leading up to that tragedy was hardly unique to Inpax, to Chicago, or to the holiday crunch. Amazon is the biggest retailer on the planet — with customers in 180 countries — and in its relentless bid to offer ever-faster delivery at ever-lower costs, it has built a national delivery system from the ground up. In under six years, Amazon has created a sprawling, decentralized network of thousands of vans operating in and around nearly every major metropolitan area in the country, dropping nearly 5 million packages on America’s doorsteps seven days a week.

Amazon drivers say they often have to deliver upward of 250 packages a day — and sometimes far more than that — which works out to a dizzying pace of less than two minutes per package based on an eight-hour shift.

“The damages, if any, were caused, in whole or in part, by third parties not under the direction or control of Amazon.com.”

The system sheds costs and liability, even as it grows at lightning speed, by using stand-alone companies such as Inpax to pick up packages directly from Amazon facilities and deliver them to the consumer — covering what’s known in the industry as “the last mile.” Amazon goes further than gig economy companies such as Uber, which insist its drivers are independent contractors with no rights as employees. By contracting instead with third-party companies, which in turn employ drivers, Amazon divorces itself from the people delivering its packages.

That means when things go wrong, as they often do under the intense pressure created by Amazon’s punishing targets — when workers are abused or underpaid, when overstretched delivery companies fall into bankruptcy, or when innocent people are killed or maimed by errant drivers — the system allows Amazon to wash its hands of any responsibility.

Amazon still relies on UPS and the US Postal Service for many deliveries. And it has captured the public imagination with press releases about futuristic drone delivery, which does not yet exist. But it’s this homegrown network that makes it possible to offer the amazing convenience of next-day and even same-day delivery that has become a cornerstone of its market dominance. By some estimates, nearly half of Amazon's packages in the US are now delivered this way. And the Seattle-based giant dictates almost every aspect of that operation, down to what drivers wear, what vans they use, what routes they follow, and how many packages they must deliver each day.

Amazon says its role is to lend entrepreneurs a hand as they build small businesses and not to control their companies, equipment, or labor force. It said it does not make personnel decisions for them, and while it offers them the opportunity to lease vans, purchase insurance, and manage payroll through its preferred programs, they are free to use whichever vendors they choose.

Have you had experiences with Amazon or a company contracted by Amazon that you would like to share? To learn how to reach us securely, go to tips.buzzfeed.com. You can also email us at tips@buzzfeed.com.

In response to a detailed list of questions from BuzzFeed News, it said that because many of the cases mentioned in this article are in active litigation, it cannot discuss them in detail. However, the company said safety is always its top priority and that even one serious incident is too many. It says that when accidents occur, it works with drivers or their employers to investigate claims and take appropriate actions.

In a written statement about the article's findings, the company said:

The assertions do not provide an accurate representation of Amazon’s commitment to safety and all the measures we take to ensure millions of packages are delivered to customers without incident. Whether it’s state-of-the art telemetrics and advanced safety technology in last-mile vans, driver safety training programs, or continuous improvements within our mapping and routing technology, we have invested tens of millions of dollars in safety mechanisms across our network, and regularly communicate safety best practices to drivers. We are committed to greater investments and management focus to continuously improve our safety performance.

Six days after publication of this article, Amazon issued an additional statement: "We require that all delivery service partners maintain comprehensive insurance, including auto liability so if in the rare case an accident does occur, there is coverage for all involved."

UPS and FedEx, the traditional powers of the logistics world, are deeply invested in safety. UPS, which spends $175 million a year on safety training alone, even has a policy prohibiting drivers from taking unnecessary left turns to reduce exposure to oncoming traffic, finish routes faster, and save fuel. Both firms are also heavily regulated by the government, and many of their trucks are subject to regular federal safety inspections and can be put out of service at any time by the Department of Transportation.

But Amazon’s ingenious system has allowed it to avoid that kind of scrutiny. There is no public listing of which firms are part of its delivery network, and the ubiquitous cargo vans their drivers use are not subject to DOT oversight. But by interviewing drivers as well as reviewing job boards, classified listings, online forums, lawsuits, and media reports, BuzzFeed News identified at least 250 companies that appear to work or have worked as contracted delivery providers for Amazon. The company said it has enabled the creation of at least 200 new delivery firms in the past year, a third of which are owned and run by military veterans. Inpax gets fully 70% of its business from Amazon; some companies depend on the retail giant for all of their income.

With little training, and often piloting vans in dangerous states of disrepair, Amazon drivers have crashed into cars, bicycles, houses, people, and pets.

A yearlong investigation — based on that data, along with internal documents, government records, thousands of court files, and interviews with dozens of current and former Amazon employees, delivery company operators, managers, and drivers — reveals that Amazon’s pivot to delivery has, all too often, exposed communities across the country to chaos, exploitative working conditions, and, in many cases, peril.

Public records document hundreds of road wrecks involving vehicles delivering Amazon packages in the past five years, with Amazon itself named as a defendant in at least 100 lawsuits filed in the wake of accidents, including at least six fatalities and numerous serious injuries. This is almost certainly a vast undercount, as many accidents involving vehicles carrying Amazon packages are not reported in a way that can link them to the company. And in some states, including California, accident reports are not public.

The deaths have included victims as old as Escamilla and as young as a 10-month-old baby named Gabrielle. Often with little training, and at times piloting vans in dangerous states of disrepair, Amazon drivers have crashed into cars, bicycles, houses, people, and pets. And under constant pressure to deliver ever more packages, drivers have piled parcels so high on their dashboards that they couldn’t see out the windshield — causing at least one serious collision.

In some of the cases in which Amazon was sued over road accidents, the drivers had been allowed to take the wheel despite previous convictions for traffic infractions.

Delivering packages for Amazon can itself be a perilous job. Drivers have reportedly been punched, bitten, carjacked, robbed, and shot — and at least two have died in recent years as a result of road accidents that occurred on the job.

Amazon denies any responsibility for the conditions in which drivers work, but it has continued to contract with at least a dozen companies that have been repeatedly sued or cited by regulators for alleged labor violations, including failing to pay overtime, denying workers breaks, discrimination, sexual harassment, and other forms of employee mistreatment.

And when one group in Michigan voted to join the teamsters in protest against shoddy conditions and punishing hours without overtime pay, Amazon officials acted swiftly to counter further unionization efforts.

In Southern California, Illinois, and Texas, Amazon continues to work with a firm beset by a staggering array of lawsuits from its own drivers, who said they weren’t paid properly, and from pedestrians, motorists, and cyclists, who said they were injured in collisions with the company’s trucks — even after its chief executive was accused by the firm’s own CFO of embezzling more than $1.5 million to fund an apparent gambling spree in Las Vegas.

Two drivers for a different delivery company operating in the Los Angeles area said they were forced to skip meals, ordered to urinate in bottles rather than stop for bathroom breaks, and advised to speed and not wear seatbelts to ensure they delivered more packages in less time.

Amazon’s gargantuan delivery network was born after a notorious incident remembered in the corridors of the company’s Seattle headquarters as the “Christmas Fiasco” of 2013. As e-commerce began to boom and the holiday loomed, UPS and FedEx, which then delivered the bulk of Amazon’s packages along with the US Postal Service, were blindsided by the large volume of online orders and failed to deliver many parcels by Dec. 25.

Furious, embarrassed, and determined that such an incident would never happen again, Amazon gave affected customers $20 gift cards while its executives hatched a bold and disruptive plan to free themselves from overdependence on the large, established carriers. They would develop a network of small and midsize delivery companies to take over key routes, working directly out of special Amazon delivery stations, rather than UPS or FedEx facilities, and delivering packages according to Amazon’s own routing algorithms.

The goal, according to people with knowledge of Amazon’s operations — including a former executive who helped oversee the program in its early days — was to build out a completely independent last-mile delivery system. The company said it did so because of growing demand from customers, but continues to work with established delivery companies as well.

Amazon would offer small delivery companies, many of them brand-new, a chunk of its booming e-commerce business, and in exchange would be able to wield unprecedented leverage over their logistics operations. It would also have the power to squeeze costs down in a way it never could working with behemoths such as FedEx and UPS.

Under this new system, Amazon would be able to closely monitor drivers through its routing software. It would make entrepreneurs assume the financial risk of running a delivery business. And perhaps most crucially, because the drivers would be employed by independent companies, Amazon would be able to assert it had no legal liability for their working conditions — or for any mayhem employees wrought as they raced to hit delivery targets requiring more than 99% of packages to arrive by their promised delivery date.

In short order, fleets of anonymous-looking gray-and-white vans were dashing through the streets of communities across America, stopping every few blocks to disgorge books, electronic gadgets, boxes of toilet paper, and the myriad other items that people increasingly order online.

In short order, fleets of anonymous-looking gray-and-white vans were dashing through the streets of communities across America.

For consumers, the change was hardly perceptible — unless they happened to look out their windows and notice that the familiar brown of the UPS truck and the cheerful orange and purple of FedEx came less often, replaced by slightly smaller vans that often had no markings at all.

But behind the wheel, and out on the streets, the changes were enormous.

Even though the Sprinter-style vans Amazon requires its delivery providers to use weigh several times more than most passenger cars, they fall just under the weight limit that would subject them and their drivers to Department of Transportation oversight, unlike most FedEx and UPS trucks.

In a sign of how business is booming, Amazon last summer bought 20,000 of these vans from Mercedes-Benz to be leased, through fleet managers, to its dedicated delivery companies around the country.

Applicants for jobs at UPS and FedEx are thoroughly screened and cram for challenging entrance exams before being hired. They undergo rigorous training that can last for weeks or longer, depending on the position, and are required to undergo additional training every year. Even the most minor fender benders trigger internal investigations that seek to identify who was at fault and how such accidents can be avoided in the future.

UPS, which is unionized, uses routing software programmed to minimize most left-hand and other dangerous turns. As part of their training, its drivers must go through special protocols before making certain maneuvers, such as backing up their trucks.

Amazon says it spends tens of millions of dollars on safety, and in some of its contracts with delivery companies, it demands that every driver pass a background check and drug test, have at least six months’ experience, and pass an extended road test. Job postings by firms delivering Amazon packages, however, say commercial driver's licenses and prior experience aren’t necessary. Drivers are paid either a flat day rate or an hourly wage — which generally works out to between $15 and $18 an hour, with scant perks or benefits. With constant alternation between driving and loading and unloading packages, the job is physically demanding.

One of the first companies ushered in under Amazon’s new delivery regime was Progistics Distribution, an already operating San Francisco–based logistics firm that agreed to dedicate a portion of its fleet to Amazon packages. Jose Guillermo Perez was hired by the company as a driver in spring of 2014, soon after the Christmas Fiasco.

“Dude, you need to be careful; I want to get back safe. I don’t want to die, man.”

After two days of in-office training, Perez was sent onto the hilly, chaotic streets of San Francisco riding shotgun alongside a more experienced driver to learn the ropes. Things almost immediately went haywire. Just after lunch on the first day, Perez was astonished to find the driver backing into a light post, then speeding away from the scene as if the accident hadn’t happened, without even checking for damage. After that, Perez said in an interview, things got worse. The driver continued to ignore the speed limit and blew through stop signs as he shot up and down traffic-choked streets.

“Dude, you need to be careful; I want to get back safe,” Perez recalled saying. “I don’t want to die, man.”

But the driver, Jim Kitamura, told Perez he had to hurry.

Shortly after 3 p.m., their Ford van approached a busy intersection in a residential neighborhood just as the light turned red. Rather than hit the brakes, Kitamura kept going, heading straight for a motorcycle that was accelerating through the crossing. A driver in another car noticed and honked frantically in warning, but the delivery van kept going and smashed into the bike, according to a police report.

The impact was so powerful that it not only knocked Paul Hon Chow Lee off the motorcycle — fracturing his ankle, pelvis, and six ribs — but also knocked his shoes clean off his feet, according to the police report.

Even before the crash, the events of the day had given Perez cause for alarm. He saw that drivers were given huge piles of packages to deliver and were barraged by constant nagging calls from dispatchers checking in on their progress. The vans, he thought, were in terrible shape, with worn tires and sagging suspensions, and he said he’d witnessed at least one driver smoking marijuana on the job. Perez said Progistics hadn’t done a drug test on him, and could not recall any other screening process.

Progistics did not respond to a detailed request for comment.

Police cited Kitamura for running a red light. It was far from his first driving violation. In the eight years leading up to the accident, Kitamura had been pulled over at least four times, records show, twice pleading guilty to driving more than 20 mph over the speed limit — once in 2006 and once in 2008 — and once to running a stop sign in 2011. He’d also been charged with sex crimes involving minors and was a registered sex offender.

So concluded Perez’s training.

The first day he was sent out on his own, he quit before the shift was over.

“I thought, No, this is crazy. I had 160 packages and it was raining; you can’t even see,” he said. “I did, like, probably half of it and I took the truck back and went and told the guy, ‘This is it. I’m done.’”

In the five years since it dove into last-mile delivery, Amazon’s business has boomed.

In 2018, its retail sales hit a record $233 billion, and this year it surpassed Walmart as the largest retailer in the world. In April, it promised free one-day shipping for all its Prime members — an unprecedented logistical challenge.

Not all of Amazon’s packages are carried by its network of small providers; it continues to rely on UPS and the US Postal Service for many of its deliveries, particularly for bulky packages or for rural, harder-to-reach destinations. But with FedEx recently canceling its contract to deliver Amazon packages, a growing share of the huge delivery load is being carried by the network of tiny, lightly regulated firms in its vast national network.

Delivering billions of packages a year is by far one of the company’s top expenditures. But Amazon can better control those costs by squeezing its own delivery network. It not only can track every package but also can monitor payroll, insurance, and even van leasing costs for many of its delivery companies. That allows it to keep an eye on companies’ profit margins and adjust accordingly. Early this year, for example, Amazon stopped paying delivery companies extra money to cover the cost of a dispatcher in each delivery station, requiring the companies to pay that salary out of already thin margins or operate without them.

Amazon pays many of its delivery firms a flat fee per route, so when package volumes increase and drivers need to be out on the road for longer, racking up more overtime, their margins are squeezed even tighter. One contract for a route in San Francisco reviewed by BuzzFeed News, for example, called for a fee of $279.50 per day. That money must cover the cost of the van, insurance, and any other overhead, plus the driver’s wages. Some newer delivery firms are paid a per-route fee, plus a per-package fee.

Many of them have no source of income other than Amazon and, faced with those circumstances, can find they have no choice but to cut back wherever they can.

Drivers complain of poorly maintained vans, with underinflated and balding tires, cracked or missing sideview mirrors, and, in one case, doors that had to be held shut with bungee cords. Frequently they have no backup cameras, and many don’t even have a rear window. As a result, some drivers back into things — lawns, mailboxes, parked cars, and, sometimes, people.

And then there are the corners drivers themselves cut to finish their deliveries on time and keep dispatchers off their backs. Drivers complain they are sometimes given so many packages that they don't all fit in the cargo area and must be piled on the passenger seat. Some said they pile packages on the dashboard to save the time it takes to walk around to the rear of their vans for each delivery. Having the parcels laid out at their fingertips, they explained, helps them get through their routes more quickly and avoid the wrath of impatient dispatchers. But that convenience comes at a cost.

Resty Evinger was pulling out of a parking space outside an apartment complex in Austin in March 2018 when she collided with Julia Barrera Duran. The 62-year-old was knocked to the ground, and her head hit the asphalt. According to claims in a pending lawsuit filed by Duran, Evinger had her left foot in a medical boot and walked with crutches. She quickly got out of the Dodge Ram van and knelt by Duran’s side. According to a police report, Evinger explained why she hadn’t seen Duran in broad daylight: Her view had been partially obstructed by a pile of Amazon packages arranged on the dashboard.

Amazon said that it considers a variety of factors when considering the size of loads, but said it is up to drivers to determine how to pack the vans and where to put the packages. If a driver is worried about the number of packages they are given, they are welcome to raise those concerns.

Amazon can surveil almost every driver in its delivery network. But when it comes to the pedigree of the companies it entrusts to deliver its cargo, officials are remarkably hands-off, overlooking serious safety lapses, criminal convictions, and egregious violations of labor laws.

Amazon said it expects its delivery operators to comply with the law.

In July 2015, an obscure mining firm in Idaho abruptly changed ownership and announced it was getting into the package delivery business for Amazon, under the unlikely new name of Scoobeez.

Just months after making its first deliveries, however, the company was sued by four drivers who successfully claimed they had been misclassified as contractors rather than employees. It would be the first in a string of employment, personal injury, contract, and workplace discrimination lawsuits filed against the firm.

In March 2017, the company’s CFO sent a 25-page report to the Scoobeez board of directors alleging that CEO Shahan Ohanessian had misappropriated as much as $1.5 million of the company’s funds, transferring the money to his own bank accounts and withdrawing hundreds of thousand of dollars of that money at the Wynn hotel and casino in Las Vegas. Subsequent investigations concluded that Ohanessian then took out 17 high-interest loans to cover his tracks, costing the company some $2 million in fees and interest payments — money that might have been used to pay the drivers who were suing the company for unpaid overtime or, for example, the Texas family who came home one day to find that a Scoobeez van had rolled down their driveway and into their house, smashing the side of their attached garage.

In April, Scoobeez filed for bankruptcy protection, listing, among other liabilities, monthly payments totaling nearly $7,000 for leased Bentley, Porsche, and Mercedes-Benz luxury vehicles that were made available to the company’s top executives.

Scoobeez denied, in a separate court filing, the former CFO’s embezzlement allegations, saying they were fabricated and part of a ploy to take control of the company. Ashley McDow, an attorney representing Scoobeez in its ongoing bankruptcy, said the company had nothing to add beyond what is in the public record.

As of late August, the company continues to recruit delivery drivers for locations throughout Southern California, Illinois, and Texas — and in court records, it has claimed that 99% of its revenue comes from Amazon. Newly filed personal injury lawsuits continue to roll in, and in May, Enterprise sued Scoobeez, claiming it owed it more than $700,000 for damages to vans it had leased the company.

Ohanessian and his wife are no longer with Scoobeez and lately have turned to another possible get-rich scheme: putting logistics on the blockchain.

In 2017, Courier Distribution Systems, another of Amazon’s larger delivery providers, was notified by Inc. magazine that it was one of the 500 fastest-growing privately held startups in the country. “Welcome,” the magazine’s editor-in-chief wrote in a congratulatory letter, “to the most exclusive club in business!”

Like other Amazon delivery companies, CDS — based outside of Atlanta but delivering Amazon packages in several states, including Wisconsin, California, Pennsylvania, and Illinois — was required to carry a full slate of insurance.

In addition to cargo, business, and general legal liability coverage, Amazon requires delivery firms to carry workers' compensation policies, which are designed to cover the costs of medical care for employees injured on the job as well as any lost wages.

But that system failed Aleasa Thomas, who worked for CDS in the Milwaukee area. In April 2017, while completing a delivery to a house, Thomas said, she was violently attacked by a dog, causing her to fall and hit her head.

Only later did Thomas discover that CDS — which had earned its place on the Inc. list by growing at least 10 times larger over the previous three years — had failed to pay its workers' compensation premiums in Wisconsin between February and June of 2017, meaning she was not covered. CDS was later hit with a $154,000 judgment for failing to pay workers' compensation insurance in the state.

Jim Blanchard, a CDS representative, acknowledged the four-month insurance lapse but said it occurred while the firm was applying for different coverage. He added that CDS paid all of Thomas’s “medical bills, all of her unpaid wages, and any other losses.”

Wisconsin was far from the only region where CDS appears to have fallen fell behind on its bills. The firm has faced at least two dozen lawsuits and other claims in recent years by employees who say it didn’t correctly pay them, fired them without cause, or discriminated against them. Some of those cases settled out of court. A tire company near San Diego won an $11,578 judgment against the company in November 2017 after CDS failed to pay its bills.

Elsewhere, CDS had faced a mutiny from some of its drivers. Jovon Bray, a dispatcher at CDS in Sacramento, said he was forced to quell a near riot in October 2015 when roughly 100 angry drivers showed up to work demanding to know why they hadn’t been properly paid. When Bray called a manager at headquarters for advice, he recalled being told, “You need to find a better lie to tell them.”

“The whole thing is like a joke. They had no rules established. I asked if there was a manual or a handbook, what are my expectations? They said, ‘You gotta create them as you go.’”

When it happened again two months later, Bray said he called again and declared that he wouldn’t work unless everyone — including himself — got paid on time. A few days later, he recalled receiving a phone call from a supervisor while at a holiday party. “You aren’t management material,” Bray recalled the person telling him before summarily firing him. Bray and several other workers sued CDS and eventually settled out of court.

“The whole thing is like a joke,” Bray told BuzzFeed News. “They had no rules established. I asked if there was a manual or a handbook, what are my expectations? They said, ‘You gotta create them as you go.’”

Blanchard denied the allegations. “I assume this has been fabricated,” he said. He added that “CDS has offered good-paying jobs and benefits to thousands of employees — many of whom lacked the education or skills to secure any other job paying as much as they earned at CDS — and largely without incident or dispute.”

In the wake of the uprising, CDS lost its Sacramento routes. But Amazon continues to work with the company in numerous other cities around the country.

The same labor problems that appear across Amazon’s delivery network were apparent at Inpax in the period leading up to the crash that killed Telesfora Escamilla. Just months after Amazon began working with the firm in 2015, it fell under investigation by the Department of Labor for chronically underpaying dozens of drivers and was ordered to pay employees back wages. The following year, regulators found Inpax had “willfully violated” labor laws a second time by failing to pay drivers overtime. Third and fourth investigations would uncover more violations and unpaid wages of more than $140,000.

Inpax’s founder and CEO, Leonard Wright, had a string of cocaine-related felony convictions and first registered the company shortly after finishing a three-year prison sentence for narcotics distribution. Yet despite the mounting warnings that Inpax had serious issues, Amazon kept shoveling more business in its direction. By 2016, the firm was delivering in at least five cities — Atlanta, Cincinnati, Miami, Dallas, and Chicago — Labor Department records acquired through the Freedom of Information Act show.

As Christmas of 2016 approached, Amazon was on track for what would be its biggest holiday season to date, ultimately shipping more than 1 billion packages worldwide. To handle the record-setting workload, it piled on the pressure, ramping up the number of packages each driver was expected to deliver each day.

Although the woman escaped with minor scrapes, the dog did not survive.

By then, Inpax had eliminated numerous fleet managers whose job it had been to oversee safety and operations, according to former employees. The firm had stopped repairing vans that were damaged or had missing mirrors, cracked windows, or bald tires. And, two said, it stopped paying for a state-of-the-art fleet monitoring service it had installed in all of its vehicles that tracked their location and speed and was designed to alert fleet managers if drivers were making unsafe maneuvers.

Escamilla’s death that December was not the first or last time the company’s drivers would run into trouble on the roads. Court records show the company has been served with at least five additional accident-related lawsuits since then.

In October 2017, an Inpax van loaded with Amazon parcels came around a corner in Weston, Florida, and plowed into a cockapoo that had run into the road before the eyes of its owner and her two young sons. When the distraught woman banged on the window in outrage, the driver hit the gas, dragging her to the ground, according to a police report. Although the woman escaped with minor scrapes, the dog did not survive.

The driver told police that she called her manager at Inpax to report the accident and was instructed to leave immediately and return to the delivery station. Perez voluntarily returned with her Inpax manager later that day to speak with police, but she was ticketed for fleeing the scene of the accident and ordered to pay $1,500 in restitution, court records show.

The dog's owner is suing Inpax and the driver for physical and emotional damages, claiming that Perez had been “speeding down the street.” Inpax countered that the incident was solely due to her own “carelessness and negligence” in letting her dog stray into the road. Amazon was not sued; once again it escaped liability.

Traivon Hemingway, a slender 21-year-old who delivered packages in and around Chicago for Amazon delivery provider Sheard-Loman Transport, was attempting to make an exit off an interstate southwest of town on the morning of June 19, 2018, when the Ford van he was driving struck the back of a tractor trailer parked on the highway shoulder.

The force of the impact tore off the top of the van and drove the rest of the vehicle under the trailer. Emergency workers tried but failed to resuscitate Hemingway at the scene of the crash, where he died.

News of Hemingway’s death spread quickly through the Amazon delivery station on the South Side of Chicago where he’d worked, but there is no record of his death being investigated by workplace health and safety officials. News reports about the accident never linked Hemingway’s death to his work for Amazon, but a GoFundMe page set up by his sister received a $100 donation from Bill Seliger, an Amazon executive who managed delivery-firm accounts in Chicago.

Hemingway’s van was eventually returned to Sheard-Loman, which has been sued three times in the last year by former employees claiming they were cheated out of overtime and other wages. All three suits are pending.

Sheard-Loman did not respond to a written request for comment.

More than a year after his death, one of Hemingway's relatives in Chicago was still frequently posting about his death on Facebook. "Not a day goes by that I don't think of him and still cry," she wrote on Aug. 30. "Missing you so much Traivon Hemingway until we be together again."

When delivery drivers complain about the harsh conditions they face, Amazon refuses to admit any responsibility. But when a group of drivers banded together to advocate for their rights to fair pay and safe conditions, executives at the e-commerce giant moved quickly to quash any further such efforts.

In March 2017, a group of drivers for the delivery firm Silverstar Delivery met with a Teamsters organizer at a TGI Fridays outside of Detroit to complain about the shoddy condition of the vans they drove, Amazon GPS devices that conked out at crucial moments, and, in particular, a lack of overtime pay, despite shifts that routinely lasted as long as 12 hours.

The organizer convinced them to unionize, and the following month, Silverstar employees voted 22–7 to join the Teamsters, making it the only Amazon delivery contractor to have unionized to date.

Silverstar did not react positively to the news. Within weeks, drivers reported to the National Labor Relations Board that they were being fired for joining the union.

One of the workers claimed he was terminated in May after bringing back undelivered packages to the warehouse. When he complained, the worker said a manager told him, “I was told to write you up for anything because you joined the union,” according to NLRB filings.

The board dismissed the charges that workers were illegally fired in retaliation for unionizing, but allowed other claims of anti-union activity to proceed. Silverstar ultimately agreed to pay $15,696 to settle the matter.

The Teamsters named Amazon in their complaint, but the retailer denied having any legal relationship to the unionized workers. “While Amazon has a services contract with Silverstar, Amazon is not the employer of Silverstar’s employees,” the company wrote in a letter to the NLRB.

A few months later, Norm Collins, who had been elected shop steward, received a call from a Silverstar dispatcher who told him the company was shutting down its Michigan location immediately, putting dozens of drivers, as well as several dispatchers and managers, instantly out of work. “He said don’t report to work because Silverstar came down, packed up all their stuff, took the vans,” Collins recalled. “They’re gone.”

Not long after the successful unionization vote, a team of Amazon officials paid a visit to Chicago, where they gathered top management from delivery firms operating in the city at a hotel west of town, according to two people who attended the meeting. The topic: how to ensure that what happened to Silverstar would never happen to them.

“The whole purpose of the meeting was to say to you, ‘Here’s how to not get unionized. Because if you do, we pretty much don’t want anything to do with a union,’” said one attendee.

In July, a Canadian news site reported that Amazon had held a similar meeting to discourage organizing among drivers for Toronto-area delivery companies.

The closure of Silverstar hardly slowed down Amazon’s Detroit-area operations. Other delivery firms already operating in the area were happy to pick up the available routes.

Because of the low pay, long hours, and high stress of the job, turnover among Amazon delivery drivers is high.

Former dispatchers said it’s not uncommon for drivers to quit in the middle of their shifts, sometimes abandoning the vans on the road. If a delivery firm doesn’t have enough drivers on any given day, it risks losing routes to competing delivery companies operating out of the same warehouse. Amazon routinely monitors and ranks the performance of each provider, delivery company managers say, and rewards its most reliable performers with additional and more profitable routes.

As a result, delivery firms are constantly recruiting drivers to get on the road as fast as possible — and in an economy with national unemployment currently below 4%, former managers described a perpetual hiring crisis that requires them to accept nearly anyone who walks through the door.

Former dispatchers said it’s not uncommon for drivers to quit in the middle of their shifts, sometimes abandoning the vans on the road.

A manager at Sheard-Loman, for example, recently used Facebook to cast a wide net for potential drivers.

“I’m launching an AGGRESSIVE hiring campaign. If someone owes you money and they’re not working, if someone needs to move out yet using the excuse that they don’t have a job, if your baby’s daddy/momma is behind on child support, have them call me NOW,” he wrote. “I’m hiring on the SPOT.”

But despite the high pressure and tight margins, many companies have jumped at the opportunity to get a piece of Amazon’s home delivery business. Some have had their dreams crushed.

Two years ago, Thomas Chen, a Chinese immigrant living in Southern California, was delighted when Amazon invited him to join its last-mile delivery empire. Chen had spent several decades in the import-export business and had built a relationship with Amazon through his work bringing Chinese merchandise into the US for sale. In the summer of 2017, he said, he enrolled in a multiday training session that Amazon holds for new delivery firms and had his first five vans on the road in Portland, Oregon, starting Nov. 1.

Rather than lease vehicles, Chen invested in a fleet of 36 brand-new vans, and his fledgling firm, FM Xpress, was soon awarded several routes in the Inland Empire outside of Los Angeles. In February 2018, he spent $2.5 million to acquire an already established delivery company called Metax Logistics.

Business was good and growing fast, and so when an Amazon executive approached him in April 2018 about buying a third company a few months later, he leaped at the opportunity. The firm, NEA Delivery, had been one of the first delivery companies contracted by Amazon back in 2014 and had more than 200 vans in service, making deliveries up and down the West Coast.

Chen said he sought and received what he called a “green light” from Amazon that NEA would be a good investment, and the $4.5 million purchase was closed in a matter of weeks. By October of that year, Chen said, he had 875 drivers on the road, a payroll of $1.6 million, and was delivering upward of 100,000 Amazon packages a day.

But it turned out there was a lot about NEA that Chen hadn’t been told. The firm had been sued numerous times over employment issues and accidents involving its drivers. One such suit, filed against NEA and Amazon, involved a teenager who said he suffered a head injury in 2015 when his bicycle was struck by an NEA delivery driver opening his door into the bike lane.

Even as Amazon approached Chen about the deal, it was arguing in court that it should be dropped from that lawsuit, claiming it bore no responsibility for the teen’s injuries. The case eventually settled.

“Amazon, you are so big. Why do you want to treat your business partner this way?”

Chen, who admits that he could have done more due diligence but said he trusted Amazon’s advice, had to contend not only with those cases but also with at least a half-dozen more suits that were filed against NEA after the deal closed and are still pending.

Another problem, according to Chen, was that Amazon was often extremely late in paying its weekly invoices, which stretched his finances. He complained about it during a meeting with Amazon executives in a Santa Monica hotel early this year, he said, and soon thereafter noticed that his routes had been dramatically reduced. This April, he said, he received a call from a different Amazon executive telling him that his services were no longer needed and his contracts would all be terminated in 30 days.

Chen’s three DSPs had recently been appraised at $28 million, he said, but Amazon offered him just $400,000 to sign a separation agreement and walk away. Instead, Chen filed a lawsuit, which is ongoing. In an interview, Chen claimed he believed that Amazon wanted to give away his routes to smaller, more pliant companies that would accept lower fees.

Chen, who said he’s been thrown into a serious depression by the situation, grew emotional as he described having to fire hundreds of employees on the spot.

“Amazon, you are so big,” he said. “Why do you want to treat your business partner this way?”

Chen is not alone in complaining about not getting paid by Amazon.

Lisa Bythewood of Tampa, Florida, signed her first contract to provide delivery services to Amazon in March 2015, running routes out of Miami. In less than two months, Amazon assigned her two more locations. She was excited but also noticed that the company hadn’t yet paid any of her weekly invoices, she recalls. Figuring it was just a bureaucratic hang-up, Bythewood took out a large line of credit to keep her business afloat.

By August, Amazon had awarded her company, VHU Express, an additional 17 locations, stretching from LA to Boston. But as the fall set in, she noticed that once again, Amazon was failing to pay her invoices and she started falling behind on her overhead. Bythewood took out a second line of credit, but it wasn’t enough and drivers started going unpaid.

At least one of those drivers complained to the Department of Labor, which launched an investigation in early 2016. The regulator found that 120 employees were owed a total of nearly $190,000 in back wages and overtime — but determined that nearly all of that should be paid by Amazon rather than VHU, according to Labor Department records.

It was a very unusual finding. Amazon has successfully argued, on multiple occasions in court and to regulators, that it had no responsibility for the treatment of drivers.

The DOL investigator felt differently, noting that because Amazon controlled and supervised the work and working conditions, required VHU to operate out of its facilities, mandated what screenings employees should undergo and what clothing they should wear, and could “dictate who they no longer wanted working as” drivers, it was, in fact, a joint employer.

Amazon acknowledged it had problems with its invoicing system, blaming a variety of factors, including having “moved their accounts payable department to India.” The company vigorously denied being a joint employer, but to get out from under the Labor Department’s thumb, it agreed to pay the workers. It also consented to pay back wages in Florida and Massachusetts, for a total of $352,816.71.

But that didn’t put the matter to rest.

Around the same time, Amazon terminated its contract with Bythewood, who had to lay off about 300 employees. Soon thereafter, it filed a claim against VHU in court, arguing that the firm had violated its contract, which required it to “defend, indemnify, and hold harmless Amazon from any third-party allegation or claim.” Eventually Amazon won a judgment against its former delivery company for nearly $300,000, despite the fact that it had apparently created the entire situation in the first place by failing to pay its invoices. Eventually Bythewood said she settled the dispute with Amazon out of court.

In the meantime, Bythewood, a 51-year old mother of seven, was left facing lawsuits from unpaid lenders, insurers, van leasing companies, and workers. In a bid to help her, Bythewood’s mother emptied her own retirement fund, but it was to no avail: Bythewood and her husband filed for personal bankruptcy a few months later, listing more than $1 million in unpaid Amazon invoices in the filing.

The previous summer, she had been named a finalist in the Tampa Bay Business Journal’s BusinessWoman of the Year awards because her company had landed a contract with Amazon. Now her company was gone.

“You’ve got people chomping at the bit because all they think and see is dollar signs,” said Bythewood, who currently isn’t working. It was hard to say no, she said, because if “you don’t want to do it, someone else will.”

Indeed, Amazon enjoys a glut of entrepreneurs eager for a chance at owning their own chunk of its delivery network. A Facebook group dedicated to people hoping to launch Amazon delivery companies has more than 500 members. They offer each other tips on how to pass the video interview (be sure to use Amazon’s STAR method for answering questions) and thoughts on whether or not $10,000 is actually enough to get started ($30,000 is a safer bet, some say).

“Just got the call I’ve been hoping and praying for, I’m in!” a group member recently posted. “It was a long road, since applying June 2018. God is good.”

Shortly before 3 p.m. on April 19, 2018, a driver for a delivery firm called Last Mile Delivered, Keith Heard, turned left down a four-lane road in a Philadelphia suburb, following delivery directions on his Amazon device. Worried he was about to miss a second left onto a side street, he pulled into an intersection when he heard what he later described as a “thump” and assumed he had somehow hit a pole, according to the police report.

What he had heard, in fact, was the sound of his Ford Transit van slamming into the body of Samuel Cabelus. The 22-year-old Temple University junior had been cruising on a motorcycle down the arterial at the time Heard cut in front of him, and when he tried to stop, his Yamaha hit the pavement and slid toward the van.

Cabelus was crushed under the vehicle, where he died. Heard was cited by police for failing to yield before making a left turn. Cabelus’s grieving parents declined requests for interviews but blame Amazon for the accident, arguing that the company’s policy of pressuring drivers to meet guaranteed delivery times contributed to their son’s death, according to an ongoing lawsuit they filed against Amazon, Last Mile Delivered, and Heard in late 2018.

In court, Amazon vigorously denied liability on the familiar argument that it does not control the delivery firms in its network or employ the drivers. And just as it had again and again — in cases of death, injury, and workplace mistreatment — the company invoked the carefully worded agreement it requires all delivery firms to sign, obliging them to defend and indemnify it from, or assume responsibility for, any and all legal claims. A lawyer representing Last Mile and Heard also denied responsibility for the death in court.

In the year since her son’s death, Cabelus’s mother, Winnie, has written frequent Facebook posts about missing the young man she remembered in one comment as “stubborn, handsome, funny, a great big brother, invincible, charming, and absolutely adored.” In February, she posted an article about the crash in a public Facebook group called Bad Amazon Deliveries. “Please take these unprofessional driver mistakes seriously,” she wrote. “They may cost you life.

“This is about shitty driving, yes,” she added. “But this is about low-paid, inexperienced, and untrained delivery drivers operating gigantic vans they don’t know how to drive, under enormous pressure to deliver quickly. This is profit driven, corporate greed behavior without consideration for anyone else’s humanity.”

Late on the morning of July 31, an attorney for Amazon walked into a dingy, cramped courtroom on the second floor of the Cook County Criminal Courthouse in Chicago. She was there to watch the trial of Valdimar Gray, facing a felony homicide charge in the death of Telesfora Escamilla.

Moments before the trial began, 20 members of the Escamilla family entered the courtroom en masse, taking up half the seats in the gallery. Over two days of testimony, they relived the terrible afternoon of Dec. 22, 2016. On at least a half-dozen occasions, members of the family broke out into tears, sobbing audibly when the circumstances of Telesfora’s death were described.

Gray, who had no previous driving infractions, sat stiffly in a gray blazer and a crisp white shirt. He faced a sentence of between 3 and 14 years in prison if convicted. The Escamillas had pushed hard for him to be prosecuted. The civil suit they had filed against Gray, Inpax, and Amazon couldn’t proceed until Gray’s criminal liability was determined.

Escamilla’s daughter Irma told BuzzFeed News that she had heard about her mother’s death on her way home from work. She had been looking forward to spending Christmas Eve with her mom, a grandmother of 17, who had already purchased tamales for the family’s traditional Christmas Eve dinner.

“I still have a hole in my heart for my mom. She’s not with us. I don’t know if I can overcome this.”

Instead, she found herself staring at a pool of her mother’s blood on South Drake Avenue. “I still have a hole in my heart for my mom,” said Irma. “She’s not with us. I don’t know if I can overcome this.”

Witnesses testifying for the prosecution described the accident and its aftermath, conceding under cross-examination that Gray might not have been breaking the speed limit, even if he was in a hurry, and had paused, albeit briefly, at a stop sign moments before impact.

Gray’s lawyer, Adam Sheppard, saying the evidence was inconsistent and that Escamilla’s death was a “tragic accident,” called for his client to be acquitted. The judge concurred. Gray’s parents jumped for joy as the Escamilla family sat in shocked disbelief.

But Gray showed little joy.

“I’m not going to celebrate,” he said, walking grimly out of the courtroom with his mother and father.

Letters of support filed in court by friends and family describe how the accident has changed Gray’s once-easygoing personality and how he’s haunted by memories of that afternoon.

On that day, as dusk fell on the corner of West 28th and South Drake, amid crying members of the Escamilla family, gawking rubberneckers, and crowds of local TV news reporters, another Inpax employee quietly arrived on the scene to drive Gray’s Nissan van and the Amazon packages it held back to the Amazon delivery station, just 2 miles away.

Gray was fired the next morning and soon had criminal charges hanging over him. The Escamilla family lost its matriarch. But those boxes and envelopes were absolutely going to get delivered by Christmas.

The urgent memo Amazon sent to Gray’s supervisors at Inpax just five days before the fatal accident described the week as the “home stretch/final sprint” and urged that every driver be made “aware of the expectations for this week.”

“Our #1 priority,” it said, “is getting every package to the customer on time.”

Nowhere did it mention safety. ●

UPDATE

This story was updated with an additional statement from Amazon.