The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Incoming.

Forty minutes after I got a possible COVID-19 vaccine as part of a clinical trial, I rode an electric moped home through the streets of Brooklyn feeling more free than I had in months.

My arm ached, the sky shone blue, and I sung “vaccine, vaccine, vaccine, vaccciiiiiinnnneeeee,” to the tune of “Jolene.” (Dolly Parton had helped fund a different vaccine than the one being tested by the drug company AstraZeneca, whose large study I am taking part in, but honoring her in that moment still felt right in spirit.)

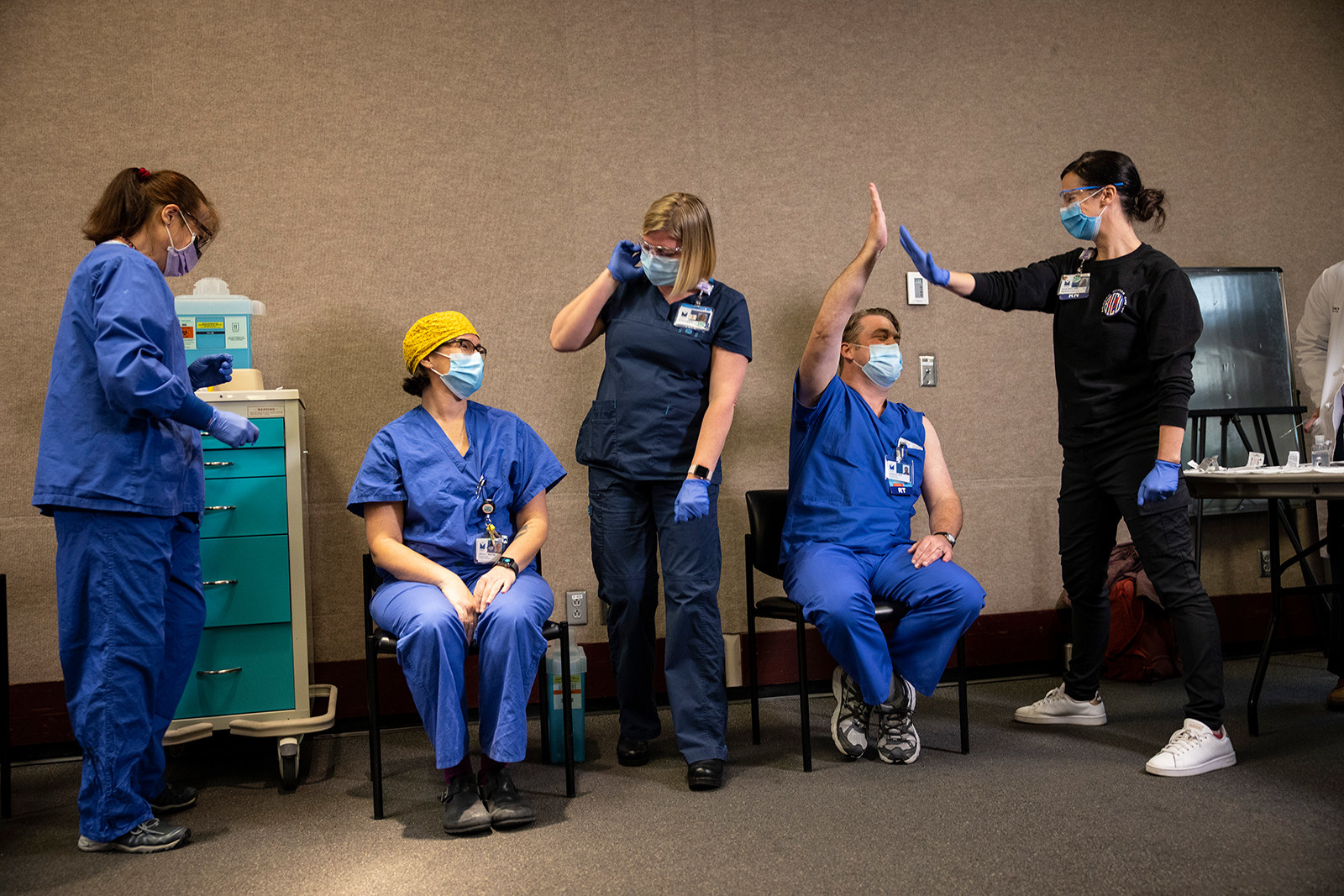

Tens of thousands of people around the world are currently participating in clinical trials to test the first COVID-19 vaccine contenders. One of them, made by the drug company Pfizer, was just authorized by the FDA last week, setting off a historic effort to vaccinate the majority of Americans to stop the spread of the coronavirus. Another, made by the biotech company Moderna, is expected to be authorized later this week. Both vaccines showed a 94%–95% success rate, require two shots spaced weeks apart, and were not linked to serious side effects. Several other drug companies, including AstraZeneca, are in final testing stages.

I’m one of over 40,000 people who will be in AstraZeneca’s US trial (trials are also being run in the UK, Brazil, and South Africa). Most clinical trials give half of the participants a placebo and the other half the vaccine, comparing the number of people who end up getting sick with COVID-19 in each group to figure out how well the vaccine works. In AstraZeneca’s, 66% of its participants get the vaccine.

After receiving my first injection last month, questions about how well the vaccine works and concerns about the company’s lack of transparency have grabbed headlines. But I didn’t know any of that yet.

I first filled out an online form in August looking for people to be involved in a COVID-19 vaccine trial. I’m in my thirties, healthy, live alone, and saw it as my civic responsibility. Volunteering for a trial felt like the perfect mix of being selfless — a practical way to help others, knowing that lots of people wouldn’t be able to risk their health or qualify and that tens of thousands of volunteers were needed to get a vaccine authorized — and also extremely self-serving, because it meant I might have access to a vaccine months before I would otherwise qualify for it.

Participating in a clinical trial — especially one that was sometimes controversial — often felt like a test of how much trust I really had.

Iris Explosion, a 33-year-old Brooklyn social worker also in the AstraZeneca trial, told me she volunteered for similar reasons.

“There’s been such a feeling of helplessness this whole pandemic and this is something I can do — I can put my body on the line to help,” she said. “But also, the idea I could be vaccinated for COVID in a week was really cool.”

Seeing the process step-by-step ended up showing me how much trust we need to place in others to end this pandemic — from the healthcare workers who care for us, to the scientists who developed these vaccines at record speed, to the governments that will distribute it, to the people in our communities who will need to get vaccinated to stop the virus’s spread.

And trusting pharmaceutical companies — which have historically tended to prioritize profits over people — may be most difficult of all. A new ABC News/Ipsos poll released Monday found 40% of Americans would take the vaccine as soon as it was available, while 41% plan to “wait a bit” before getting it. Participating in a clinical trial — especially one that was sometimes controversial — often felt like a test of how much trust I really had. And it showed me how important, but difficult, it might be to pass that trust on to others.

In October, I got a phone call asking if I was still interested in participating in AstraZeneca’s final, phase 3 trial, which had been delayed two months after two people got ill in the UK study. The AstraZeneca vaccine, known as AZD1222, was developed at Oxford University in the UK. The vaccine doesn't have the coronavirus in it — instead, it’s a type of harmless chimpanzee virus that can instruct human cells to make a coronavirus protein. This triggers your immune system to recognize and attack the coronavirus, giving you the same antibodies it would if you had already recovered from COVID-19.

My first medical appointment in mid-November took around four hours. I hadn’t yet been accepted into the trial — this was to run me through all the information, sign my agreement, go through a litany of medical tests and questionnaires, and see if I qualified. If I was accepted, I’d have a COVID-19 nasal swab, have blood taken, and then receive the first injection at the end of the appointment.

Upon arrival at the hospital, I was thanked profusely for volunteering to be involved, an encounter I experienced repeatedly with every one of the nurses, doctors, and researchers I met. It felt surreal to be thanked by people I feel overwhelmingly grateful for, healthcare workers who have risked their own lives for us every day this year. Over a free snack of graham crackers, I read the 27-page document outlining the study, the risks, side effects experienced in the trials in other countries, issues from other vaccines, and what exactly is involved in being in the trial.

I learned that the total amount of blood I’d have drawn over two years is 82 teaspoons.

The guide noted the most common symptoms were pain and tenderness in the arm where the shot is given, muscle aches, and headaches. After the first injection there’s a follow-up phone call a week later, then a booster injection a month later and another call. My blood will be tested to see if I develop antibodies from the vaccine — a month after the initial injection and then another five times, to establish how long immunity to the virus might last. I learned that the total amount of blood I’d have drawn over two years is 82 teaspoons.

Reading the study guide of the trial was a little worrying, I’ll admit. Three participants in trials of the vaccine overseas had been diagnosed with transverse myelitis, a rare neurological disorder that affects the spinal cord. Of the three, one had been later diagnosed with preexisting multiple sclerosis, which can cause transverse myelitis, one had received the placebo shot, and one had received the vaccine. A six-week-long safety investigation by the FDA determined that there was no evidence of a link to the vaccine, and they’re continuing to monitor the patient.

It’s common for clinical trials to be paused for safety investigations like this — with tens of thousands of participants, people will still get sick with things unrelated to the vaccine. But I knew from media reports that AstraZeneca had initially only disclosed one of the illnesses during a private call with investors. The New York Times has since reported that the drug company even withheld information from the FDA. Of course, the document didn’t mention that the pharmaceutical company had been secretive about the ill participants.

One of the reasons I decided to continue with the trial despite these misgivings was knowing that if I did get sick with COVID-19, I’d have a higher level of care. After getting the shot, I’d have to update an app weekly, noting any COVID-19 symptoms. If I tested positive, I’d have to collect saliva samples and wear an armband supplied by the vaccine center, which monitors my heart rate, temperature, and oxygen levels and sends updates to the medical staff.

During that first appointment, a nurse came in and asked if I had any questions and if I was ready to sign the paperwork. I was most interested in knowing whether I would be allowed to get another vaccine if, later on, there were widely available shots that were shown to be better than the AstraZeneca one. The nurse explained that if a vaccine became widely available, it would be unethical to deny participants in clinical trials this standard of care. Official guidance is still being worked out, but there was nothing stopping me from dropping out of the trial at any moment, no questions asked.

Small interactions like this reminded me that even if we think of science as this strictly rules-based, evidence-based endeavor, clinical trials are also just made up of regular people.

I asked if I would get any symptoms, such as a sore arm, if I just got the saline solution. The nurse raised their eyebrows and asked what I thought. I said I’d heard that other trials had used another type of vaccine as a placebo — being in a “double-blind” trial means the participants and trial staff are not supposed to know which shot is given — but it’s usually pretty clear when someone gets a saline injection because they don’t have any symptoms. The nurse nodded in agreement and noted that people often guess fairly accurately.

After hearing my Australian accent, the nurse noted that a lot of foreigners were part of the trial. Were Americans more likely to be skeptical about science? Or be worried because of a history of medical testing on people of color? Or be more individualistic and less focused on the greater good? Probably all of the above, we decided. The nurse also told me that if I got an antibody test in a few weeks to see if I got the real vaccine — something I had not even considered doing — not to tell them about it.

Small interactions like this reminded me that even if we think of science as this strictly rules-based, evidence-based endeavor, clinical trials are also just made up of regular people. People who are following the rules to the best of their ability but also realize other people might break rules or have certain worries. Also, like the rest of us, these healthcare professionals haven’t had much social interaction for months and love to chat and trade stories.

Once I’d signed the forms, it was time for the medical tests to begin. First, a nurse quizzed me extensively about my medical history — Did I smoke cigarettes? Had I had major surgery? Had I had cancer or an organ transplant? Then I hopped on the scales, had my blood pressure checked, and peed in a cup for a pregnancy test.

A doctor came in and performed a neurological test — Could I press my left arm against hers? Could I raise my right leg? — and a physical, feeling my glands, checking my heart rate, and pressing down on my stomach area to see if I felt pain. After not seeing a doctor all year, it was oddly comforting to have someone gently poke and prod at me to check all the parts were still working.

“You’re an ideal candidate and you qualify for the trial,” the doctor finally announced, and I cheered in excitement.

Part of the reason I qualified is that the trial focused on people who are at an increased risk. My job is predominantly at home, but occasionally I’m out in the field reporting, in large crowds at protests. I am to continue my regular pandemic life of taking precautions, being masked, and social distancing, but the nurses told me they needed people who are not entirely locked up at home and instead go out for work, catch the subway, and grab a drink with friends. That way they can know how well the vaccine works out in the wild, by comparing it to how many people in the placebo group end up getting sick.

“That’s the drug deal done,” the nurse declared.

I received a prepaid credit card that would be topped up with money — the trial pays me around $100 for each in-person appointment and blood sample, and $20 for phone visits, for a total of around $1,000.

Then it was time for blood samples, including one for additional genetic research that I agreed to, and a nasal swab to test for a coronavirus infection. The shot was ordered from the pharmacist and I jokingly asked the nurse to make sure I got the real one.

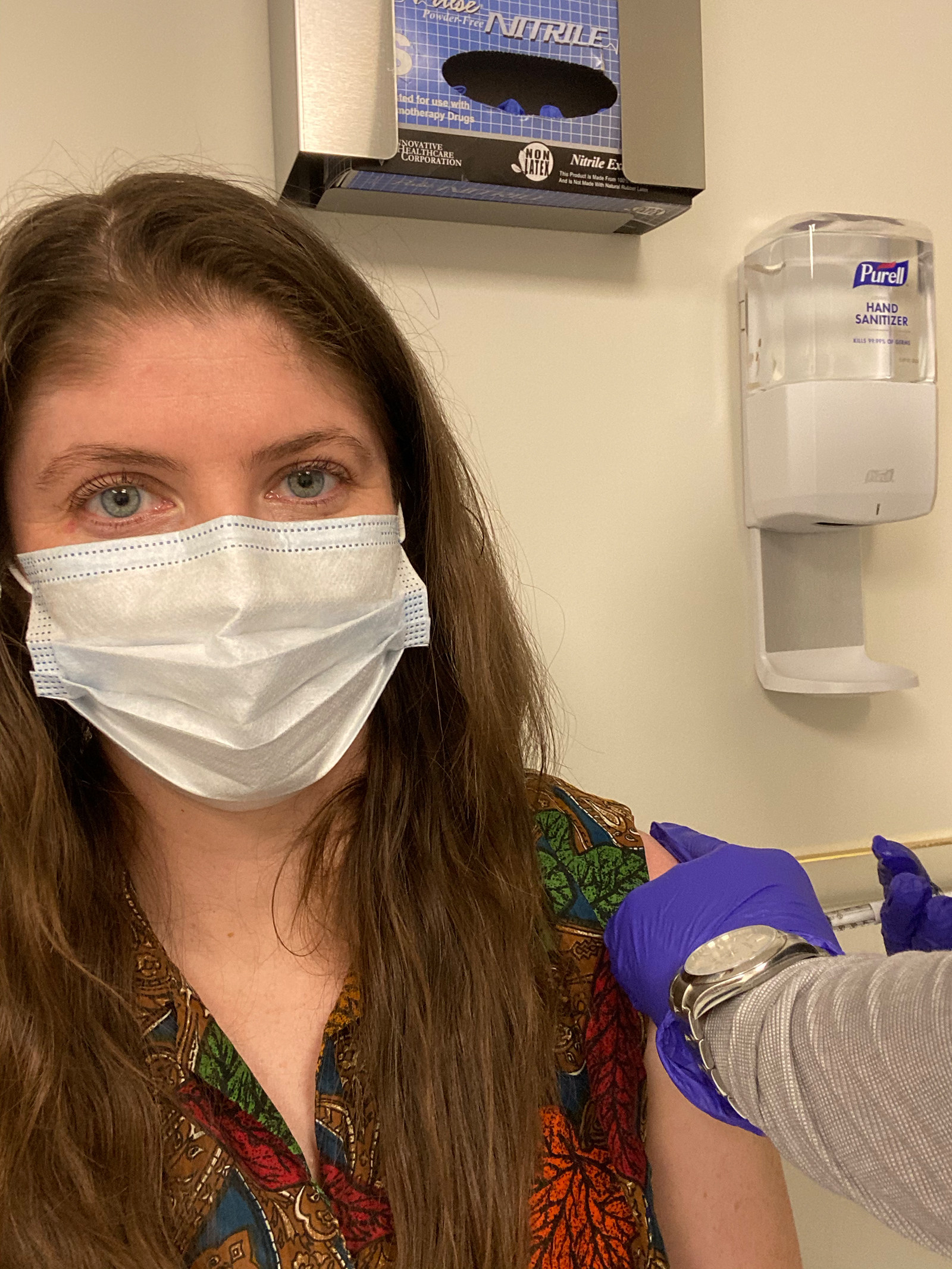

Injection time: It was quick and basically painless, like getting the flu shot.

“That’s the drug deal done,” the nurse declared.

After waiting 15 minutes to monitor for any reaction, I was allowed to leave. My arm was feeling sore and tender, which thrilled me as that indicated I’d possibly gotten the real deal.

By the afternoon I felt exhausted. That night I fell into bed at 8:45, unable to keep my eyes open. Just after midnight I woke up writhing in bed with chills.

“not feverish. just like a bit uncomfortable and like hot and cold,” I texted my sister, who is currently coordinating a vaccine clinical trial in Australia. “if this is my brain imagining my brain is powerful.”

“Your brain IS powerful,” she responded, unhelpfully.

After an hour of angrily scrolling Instagram and struggling to fall back asleep, I checked my temperature at 1:25 a.m. 100.5! I felt vindicated. It was the first time the thermometer had been over 98 since I bought it during the peak of the pandemic.

“I have a fever!!!!!” I texted my high school best friend, who is a nurse. She told me to immediately take acetaminophen, which made me realize that none of the nurses in the trial had warned me about a fever or suggested any medication if necessary. Taking drugs to lower my temperature hadn’t even occurred to me.

An hour later, after taking acetaminophen, my temperature had dropped to 99.8 and I was still miserable. I finally fell asleep at 4 a.m.

Having side effects that first night wasn’t terrible — I would take them any day of the week over COVID-19 — but I still hadn’t quite been prepared. I logged on for work an hour after the injection, but I was tired and scattered — which is fine when you work from home, but a lot of people don’t have jobs like mine. The next day I felt slow but fine. My temperature was normal. My arm was a bit tender, and I felt tired, which was unsurprising since I’d spent half the night awake.

I texted back and forth with my friend and fellow reporter Anna Sanders, who’d also gotten an injection the day before as part of the vaccine trial, comparing symptoms. She’d also been slightly feverish, tossing and turning all night. But as my symptoms improved in the morning, hers got worse.

“Saturday I was basically curled in a fetal position on the bed. I was in so much pain,” she told me later. Sanders, 29, has psoriatic arthritis, an autoimmune condition, and fibromyalgia, and believes her health conditions likely exacerbated her reaction. Saturday afternoon, her fever hit 100.

“I literally was out for the count for three days,” Sanders told me, telling me she had constant muscle aches and pains. Iris, the Brooklyn social worker, also told me she had a fever on the evening she received the first injection. For me personally, I was expecting a reaction similar to my annual flu vaccine, and this injection left me feeling a lot more exhausted, feverish, and sore.

When the FDA authorized Pfizer's vaccine last week, health officials warned that it came with more immediate side effects — making it most comparable to the aftermath of getting the shingles vaccine.

We need to talk more openly about these normal and expected side effects. While the focus by public health authorities and pharmaceutical companies has rightly been on ensuring a safe, effective vaccine, I worry that if we’re not up front about the side effects, people will question the credibility or safety of a vaccine when they hear of friends feeling unwell in the days immediately following an injection. This is especially worrying since disinformation around vaccines and trials has become a growing issue in online and Facebook groups supposedly concerned with “wellness.”

We could use a public health campaign encouraging paid sick leave after the vaccine. Authorities could prepare people for their “vaccine day” in the way they do citizens before a natural disaster: making sure they have a plan, access to a thermometer and medication, and a clear understanding of the possible outcomes or problems and how to handle them if they occur.

The day after I got my injection, I woke up to a forwarded message from my neighbor: It was a pseudoscience poster titled “How to legally decline a vaccine.” My neighbor, a Black man in his seventies with underlying health conditions, is in one of the highest risk groups for COVID-19. He’s now forwarded me multiple WhatsApp messages about how the government is trying to mandate vaccines (untrue) and an excerpt of the “Plandemic” propaganda video, which talks about how pharmaceutical companies are the biggest corporate lobbyists (true, although the rest of the film is filled with dangerous inaccuracies).

I understand his skepticism. There’s been a long history of unethical medical experimentation done on Black, Latinx, and Native people in this country. Testing for the contraceptive pill was done on Puerto Rican women living in poverty in the 1950s, who were not informed that the pill had not been approved or that they were part of a clinical trial. At least 17% reported major side effects including nausea, vomiting, and headaches, and three women died. The dosage of the pill was later lowered.

As a white person, it felt like an obvious decision at this time to risk my own body to help gather data to assure others.

In the Tuskegee syphilis study, 600 Black male sharecroppers in Alabama were told they would be receiving free government healthcare. Instead, they never received proper treatment, only getting placebo medication, so that the government-funded study could see what happened when syphilis went untreated. The “study” ran until 1972, even though by then penicillin, a treatment for the disease, had been readily available for decades.

The Tuskegee example is the most famous, but far from the only example of authorized medical testing on Black bodies, with gynecological surgeries performed on enslaved women in the 1800s and experiments on Black prisoners in the 1950s.

In the case of COVID-19, Black and Latinx people have died in higher numbers, in part because of the effects of systemic racism — denser housing, more essential work, and poorer access to healthcare. A vaccine will help stop the spread of the virus, but it will require people trusting that it’s safe to take. As a white person, it felt like an obvious decision at this time to risk my own body to help gather data to assure others.

Three days after I got my first shot, AstraZeneca released results from its UK and Brazilian phase 3 clinical trials claiming the vaccine was up to 90% effective.

But the results were both confusing and a bit misleading. The vaccine was 62% effective if participants were given one full dose followed by a second at least one month later, like I’m getting. By mistake, researchers gave one small group a half dose followed by a full dose, and those results showed a much higher 90% efficacy. Despite the error and the limited data, the drug company’s press release highlighted that higher efficacy result, and the headlines followed.

After the 94%–95% effectiveness news from Moderna and Pfizer, the AstraZeneca results felt a little, well, disappointing, even if the flu vaccine is on average only 40% effective, and I still get it yearly. The fact that they hyped inconclusive results also didn’t inspire my confidence in their transparency or rigor.

Last week, results from AstraZeneza’s Oxford trial were published in a peer-reviewed publication, with scientists continuing to voice concern that initial results were confusing and oversold, and that the best results from the trial were because of a mistake.

“Feels like we got the knockoff cheap vaccine lol,” Sanders texted me after the results were released. The AstraZeneca vaccine is literally much cheaper, costing $3–$4 a dose compared to the $20–$25 cost for Pfizer and Moderna. It can also be stored at normal refrigeration temperatures, as opposed to Pfizer’s, which must be storedin expensive, ultra-cold freezers. The AstraZeneca vaccine will be sold at cost price to developing countries — which could mean poorer countries will get less effective vaccines — and is expected to make up nearly 60 percent of the US vaccine supply.

Five days after my injection, a nurse called me. I had expected this follow-up call to be a discussion of my reaction to the injection, ready to do my part for science and tell my story about the 100.5-degree fever, major fatigue, and three days of a tender arm.

Instead, the nurse asked me if I had experienced COVID-19 symptoms for more than 48 hours at any time in the last week. Since none of my symptoms lasted more than 48 hours, I said no to all of them. It worried me that the focus was on if I’d developed COVID-19 and not how I’d reacted to my shot.

As my colleague Nidhi Prakash, who first got sick with COVID in April and has yet to fully recover, recently wrote, a vaccine won’t solve everything. The country has already lost over 300,000 people, thousands are dying every day, and their loved ones will continue to suffer. With 17 million confirmed cases nationally, it’s likely thousands will endure complications for months or years to come. And we still don’t know whether the vaccines will prevent you from getting infected or from infecting others (versus getting sick), meaning we’ll all have to keep wearing masks and social distancing until the spread of the virus slows to a stop.

But mass vaccination is still our best bet for a return to normal life. Even with my concerns about pharmaceutical companies prioritizing shareholders over public information, and even if I perhaps received a less effective vaccine, getting any possible vaccine felt like a preview of what the rest of the world will experience in the months ahead.

I asked Sanders how she felt being involved in the trial, even with the not-perfect results. “It sounds so dorky, but hopeful,” she told me.

That’s how I feel too. Hopeful for a time soon when I don’t fear the virus running through my 100-year-old grandmother’s nursing home, when I can host crowded dinner parties in my apartment, jump on a packed subway to a bustling newsroom, and even fly to Australia to hug my nephews who won’t stop growing, without having to spend two weeks locked in a quarantine hotel room.

As I wait to get my booster shot later this week, I keep thinking about being in Philadelphia in the days after the 2020 election, before Joe Biden was declared winner. The election wasn’t called until Saturday, but the street parties began in Philly on Friday morning, when it became clear Biden would win Pennsylvania and therefore the election. Being part of a vaccine trial feels a little bit like that — one day early to the party and you’re just waiting for everyone else to join you on the dance floor. ●

UPDATE

This story has been updated to clarify that AstraZeneca trials are being run in the UK, Brazil, and South Africa.