In some ways, the COVID pandemic has felt like the world’s longest dodgeball game: Only a few players remain untouched by the virus that has already killed over 1 million people in the US alone and seriously injured or otherwise impacted millions more around the world.

Now it’s clear the coronavirus is here to stay, which suggests annual rounds of an unpredictable game no one has agreed to play.

So our new reality begs the question: What does a life where COVID strikes our immune system over and over again look and feel like?

Repeat infections happen all the time with the flu and other respiratory viruses, including the handful of milder coronaviruses known to cause the common cold. These reinfections don’t worry doctors or anyone else that much.

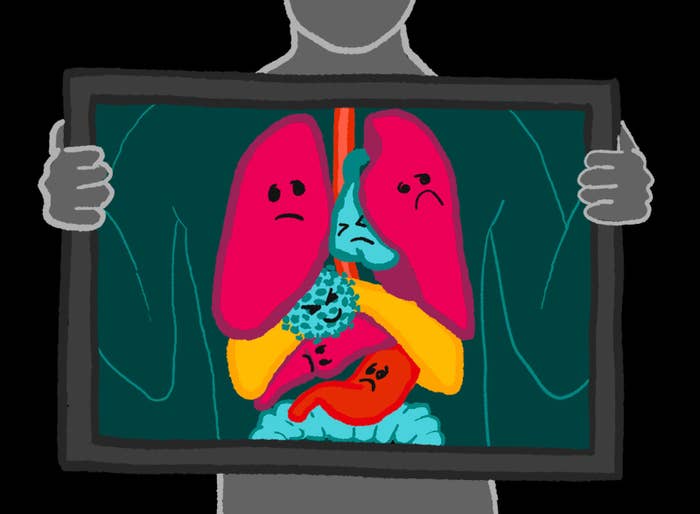

In fact, studies show you can expect to catch these other coronaviruses at least one to two times a year. But SARS-CoV-2 is unlike any other virus we’ve seen before; it can affect nearly every organ and system in the body, even months after an infection subsides, and it has a high mutation rate with the potential to produce immunity-evading variants.

Put together, its characteristics make it difficult to understand what repeat exposures mean for our bodies in the short and long term. Despite the unknowns, most of the experts we spoke to agreed on one point: Each new infection does carry some risk, and early evidence suggests the negative effects may accumulate over time.

“You may dodge [serious outcomes] the first, second, or even third time around, but you might not be as lucky the fourth time,” said Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly, chief of research and education service at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System. “Every infection is an opportunity for you to develop a problem with the virus; you can’t possibly avoid it forever.”

What is the COVID reinfection rate?

It was one of the great unknowns early in the pandemic, but we now know that you can get COVID more than once. In fact, there doesn’t appear to be any limit on how often you can get it. A person is considered to be reinfected if they test positive again after they first had COVID and recovered (including negative tests in between).

In a study of COVID-positive people in California and New York, about 4.6% to 6.3% had previously been infected. During the Omicron wave, people ages 19 to 29 living in Iceland had a 15% reinfection rate. The rate was around 12% in those who'd had one shot of the vaccine and 11% in those with two shots, according to a research letter published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in August.

While vaccination can reduce the risk of reinfection, severe symptoms, hospitalizations, and death, its effectiveness depends on how well the shot matches the circulating variant.

(Federal health officials just authorized a new booster that targets the latest BA.4 and BA.5 Omicron variants and announced that Americans should now get a COVID shot, which will be updated each year, alongside their flu vaccine every fall.)

A previous infection does offer some protection against your next one; one study found that it was associated with an 80% lower risk for subsequent infection. The protection lasted for at least six months. But if a new variant emerges that’s significantly different from the last version of the virus, then you may get infected sooner than that.

This is what happened during the Omicron wave, which helps explain why some people tested positive a second or third time within a few months’ time last winter.

Is it bad to get COVID over and over again?

Any infection — whether it’s viral, bacterial, or parasitic — taxes the body to some degree, which can differ drastically from one person to the next. What happens after an exposure depends on your vaccination status, previous infections, immune system, health conditions, and many other factors.

A COVID infection, particularly the first one, can drive your body to create protective antibodies and memory cells that help it to more quickly and efficiently defend itself the next time it's exposed to the virus. (Vaccination spurs the body to create this protective shield while avoiding dangerous or life-threatening symptoms.)

We know, too, that this protection wanes over time. But some believe that an infection (no matter how mild or severe) may, for certain people, cause damage that can weaken their ability to fight off illness the next time they contract COVID.

At least one study released in June that has yet to be peer-reviewed seems to support that theory. Researchers analyzed more than 5.6 million US veterans’ health records and found that repeat COVID infections (with a mixture of the Delta and Omicron variants) may have a cumulative effect, each positive test bringing greater risks of serious health consequences such as heart, kidney, gastrointestinal, and neurological disorders.

These risks, which were present regardless of vaccination status, persisted even six months after reinfection, at which point they entered long COVID territory. The median amount of time between a first and second infection was about two and a half months, and about two months passed between the second and third infection. (The results were adjusted for demographic and health characteristics.)

Put simply, “getting hit with a baseball bat once is better than getting hit five times,” said Al-Aly, who is the lead author of the study. This phenomenon is also common following reinfections with Dengue fever, a mosquito-borne illness that occurs in tropical regions, Al-Aly told BuzzFeed News, in which any subsequent infection increases the risks of developing severe sickness.

It’s an idea called the “multiple hit hypothesis,” according to Erin Sanders, a clinical scientist studying long COVID and Lyme disease at MIT. “For a number of environmental exposures, genetic predispositions, and stressors that you encounter, it may lead to somebody being more prone to infection or severe illness and that's something that I very much think is going to be at play with all of this.”

Not all experts think reinfections can cause cumulative damage

Dr. Shira Doron, an infectious disease physician and hospital epidemiologist at Tufts Medical Center, recommended that people take Al-Aly’s findings with a grain of salt. Because the study only included veterans, who tend to have more underlying health problems than the general public, Doron doubts the results are generalizable to everyone else.

“We know that over any period of time, and certainly over the period between one infection and another, chronic underlying conditions can get worse. That’s the natural course,” Doron said. “I don't want people to think that the norm is to have chronic disease as a result of the first infection and then worsening chronic disease as a result of each next one.”

Some of Doron’s skepticism is based on research that shows adults and children experience similar or less severe symptoms during their second COVID infection compared with their first, and that the risk of reinfection decreases over time.

Gerardo Chowell, an epidemiology and biostatistics professor at the Georgia State University School of Public Health, isn’t surprised that coronavirus reinfections may cause mounting damage to your body, although he said this may not be true for everyone. Even before the pandemic, Chowell said, Americans’ overall baseline health had been declining, which can make people more vulnerable to infections of all kinds.

“People with weakened immune systems will have a harder time recovering from the virus, and that's the most significant issue here,” said Chowell, adding that he’s hopeful SARS-CoV-2 will eventually become milder. (Evolutionarily speaking, viruses don’t benefit from killing people — doing so ruins their chance of surviving and spreading in the population.)

“This doesn't mean it won’t be able to kill people, it definitely will, but perhaps not on the level that we saw during the first two years of circulation,” Chowell said.

How could repeat infections affect the body?

How and why repeat exposures might affect the body remains largely unknown. The theories that do exist mirror those for long COVID.

One explanation is that an initial infection may cause serious injury somewhere in the body that may be unnoticeable at first until a subsequent infection “pushes them over the edge,” Al-Aly said. This may be especially true for people who may not know they have a medical condition like kidney damage or a heart problem.

Another possibility is that coronavirus particles are able to remain hidden in different parts of the body like the brain, gut, eyes, and heart, silently causing damage that accumulates with each infection. There’s also the theory that COVID triggers an autoimmune response that kicks a person’s immune system into overdrive, bringing about widespread inflammation that can cause symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, muscle aches, and more.

The problem, Doron of Tufts said, is that many of these speculations have little scientific backing. “All of the things that have been on the list as potential causes haven't reliably been found in all of the people that have been studied and so it just makes it really, really hard to know.”

Can vaccination reduce the risks from reinfections?

There is at least some indication that vaccination can lower the risk of developing post-COVID symptoms. A review of 15 studies found that people who received two doses of a COVID vaccine were about half as likely to develop long COVID symptoms that persisted for over a month; this effect was stronger in those older than 60 and lowest among 19- to 35-year-olds. The findings are promising given nearly 1 in 5 adults in the US who have had COVID are experiencing long COVID, according to the CDC.

How someone responds to COVID or vaccination depends on a myriad of factors, including their health status and general lifestyle habits, as well as the circulating variant at the time and the societal preventive measures in places like mask requirements.

For now, the best way to avoid poor outcomes following each infection is to avoid infection altogether, get vaccinated, and seek treatment like Paxlovid as early into your bout with the virus as possible, if eligible.

“Every time you get infected, you’re rolling the dice for a good or bad outcome. So as you continue to play that game, you again increase your risks,” Sanders of MIT said. “One of the biggest things that anyone can do right now is to protect yourself from getting infected again, and even if you aren't able to fully prevent infection, there's something to be said for reducing the amount of virus and the dose of virus that you're exposed to.” ●