President Joe Biden on Thursday announced that the federal government has secured another 200 million doses of vaccines to be delivered by the summer, a boost in supply that will eventually be enough to inoculate every American adult.

But, facing a shortage of vaccines and the threat of dangerous coronavirus mutants, some are calling for drug makers to band together immediately to churn out more shots.

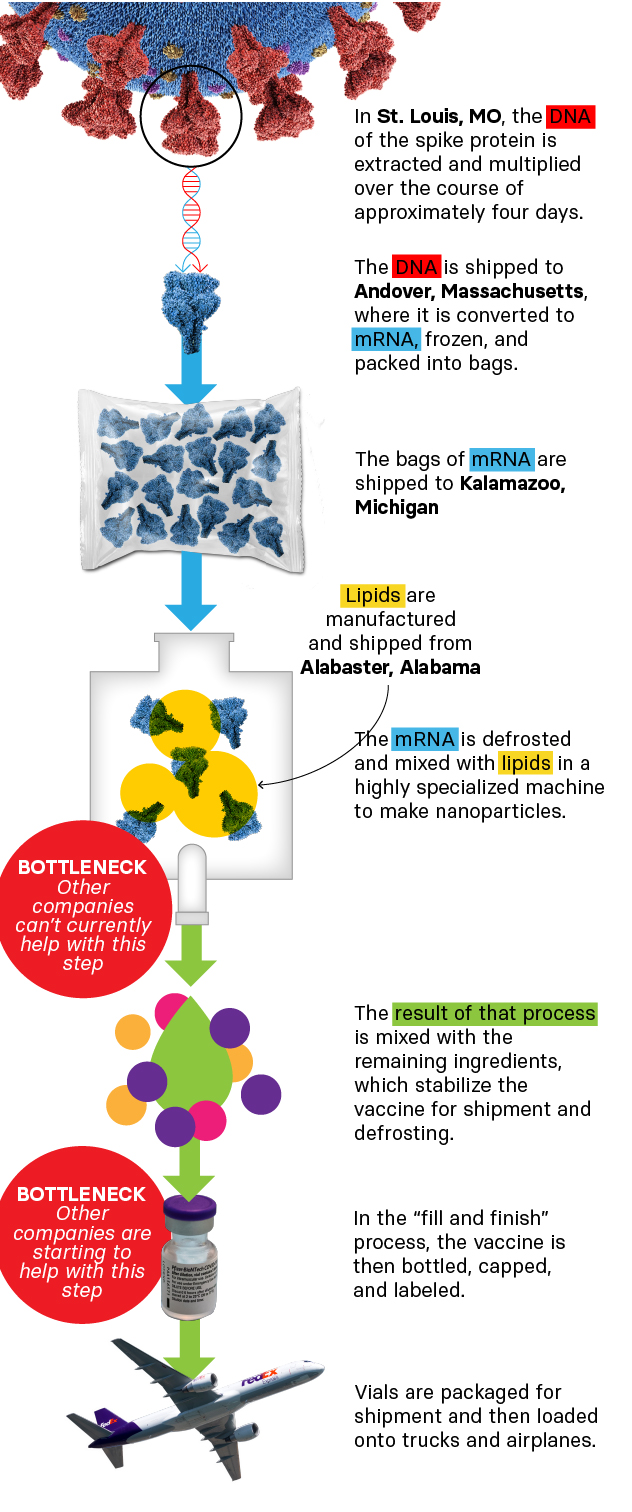

As of Friday, almost two months into the vaccine rollout, about 11 million people in the US have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19. That leaves more than 300 million people still waiting, with demand for shots now far outpacing supply.

“It is time to directly compel Pfizer or Moderna to license their vaccine to any pharmaceutical company that can help produce doses,” New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio said last week. “We need wartime mass production here in America.”

But such calls ignore reality, vaccine industry veterans told BuzzFeed News. Quick fixes by the White House, or any government, to drive up vaccine production right now may mean fewer shots if those interventions interfere with the supply chain. Accelerating production could also cause shortages of other vital medicines if factories are retooled to produce vaccines.

The problem is that vaccines are biological products, not tires or beer bottles that can be made by switching out molds on an assembly line. Making most vaccines requires first growing viruses, typically in cells or chicken eggs, and then harvesting them. The newer approaches used to create Pfizer and Moderna’s mRNA vaccines require specialized machines that aren’t found in every factory, even for large, established manufacturers. As a result, competitors can’t be much help until the FDA authorizes vaccines that can be more easily produced.

“You can scale up, but it’s more complicated than hitting a button and turning on a machine somewhere,” said Jim Robinson, a retired industry consultant who worked for pharmaceutical giants Sanofi and Merck. “Money isn’t the constraint here, it’s everything else.”

Still, some steps — such as allowing a competitor’s factories to take over the final steps of bottling, capping, and labeling the finished products — could help alleviate bottlenecks as Pfizer and Moderna struggle to get out more of their vaccines.

“Americans are eager to get vaccinated, and we’re working with manufacturers to increase the supply of vaccines as quickly as possible,” Jeff Zients, the White House’s COVID-19 czar, said on Wednesday. He argued that supply was already ramping up, with 11 million doses now being shipped nationwide each week, a 28% increase from when Biden took office.

In response to questions about whether the White House would step in to help boost manufacturing sooner, Andy Slavitt, a White House COVID-19 response adviser, said last week that “everything is on the table.” The administration is reportedly considering whether to partner competing manufacturers that are normally barred from working together because of antitrust laws. And last week, Biden invoked the wartime Defense Production Act to prioritize manufacturing pumps and filters that Pfizer needs to make its vaccine.

The vaccine makers are also taking some shortcuts to speed production on their own, rather than handing over the wholesale manufacturing, like de Blasio called for. On Wednesday, the New York Times reported that Merck, the world’s second-largest vaccine maker, might assist Pfizer or Johnson & Johnson. The drugmakers Sanofi and Novartis have agreed to bottle hundreds of millions of doses of the Pfizer–BioNTech mRNA vaccine in Europe. On Friday, the FDA allowed Moderna to fill its vials with 14 doses instead of 10, a simple way to deliver more vaccines without major manufacturing changes.

Pfizer and Moderna declined to respond to questions from BuzzFeed News about the bottlenecks they face in ramping up production of their vaccines. But in a statement on Thursday confirming Biden’s purchase of extra doses by this summer, Moderna chief executive officer Stéphane Bancel said, “We continue to scale up our manufacturing capability, both in and outside of the United States. Our goal is to bring our vaccine to as many people as possible.”

With vaccines, the process is the product.

The difficulty in scaling up production led Operation Warp Speed to steadily lower its projections for vaccine output last year. The $18 billion public-private partnership initially pledged to deliver 600 million US doses by December, a promise that eventually slid down to 40 million, a target it also missed.

OWS spent billions setting up vaccine factories to start production last year, before the shots were even shown to work. That bet paid off as vaccines started to be shipped out to states days after the FDA’s authorization. But getting those factories working hasn’t been easy. Johnson & Johnson, whose vaccine candidate will soon up for FDA authorization, revealed last month that manufacturing troubles led the company to fall two months behind schedule. The company is now promising fewer than 10 million doses by February.

“The process is the product” is the pharmaceutical industry saying about vaccines. That’s because when you get a vaccine, you aren’t just getting a shot. That 0.3 milliliter dose (about a hundredth of an ounce) is the final product of a vast integrated machine, distributed across many states and nations. A factory can cost around $600 million, each a giant tool with one job: making a specific vaccine.

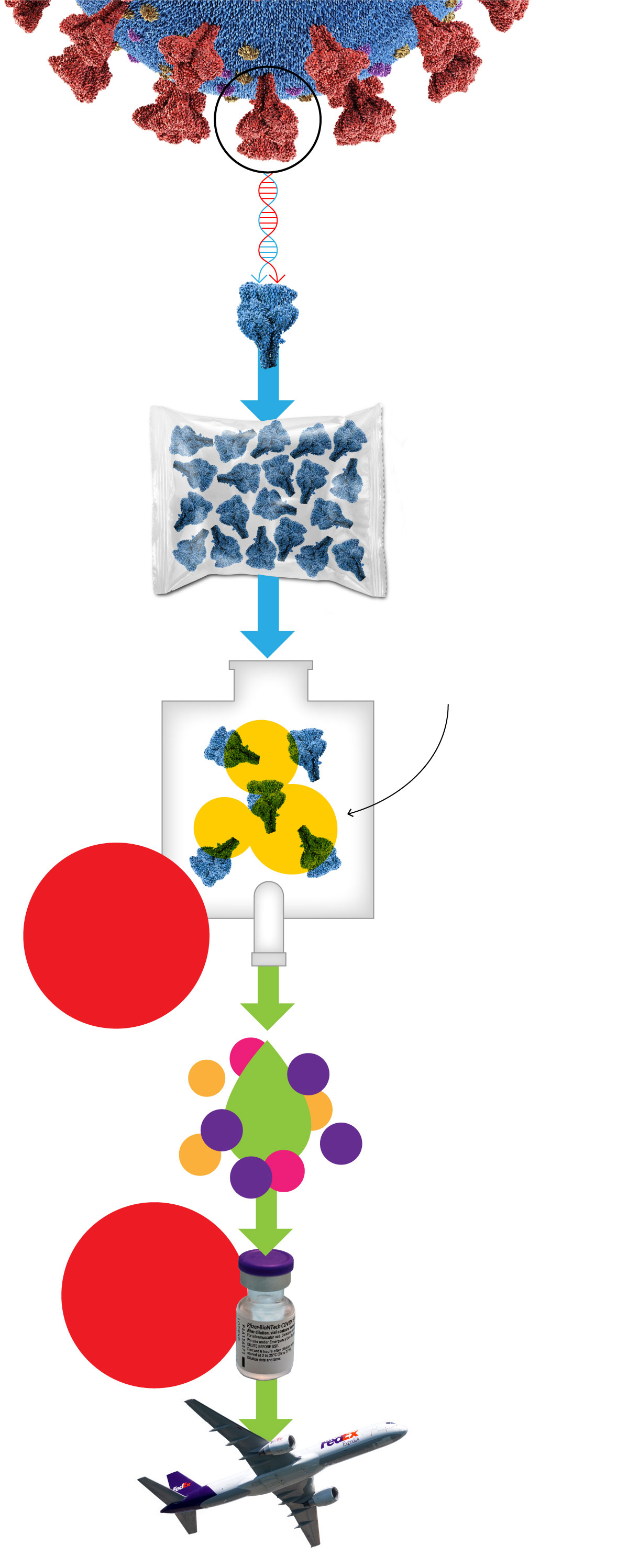

The currently authorized mRNA vaccines inject genetic instructions to make spike proteins, the part of the coronavirus that latches onto human cells. These proteins trigger the immune system to build up antibodies and other immune defenses against an actual infection. Crafting the shots is a multistep process that begins with mass-producing the mRNA molecules and then adding them to precisely designed lipids, or fat molecules, made at another facility.

The seemingly simple step of combining these two ingredients is seen as a major bottleneck in our current vaccine production: They have to be mixed together precisely as nanoparticles that are not much bigger than molecules. Not enough care with this step breaks up the mRNA, making it useless.

Aside from Moderna and Pfizer, few in the drug business can do this mixing, because nobody else has made an authorized mRNA vaccine before.

“I believe that you can count on one hand the number of facilities who can make the critical lipid nanoparticles,” pharmaceutical industry researcher Derek Lowe wrote in a blog post last week. He added, “This is the single biggest reason why you cannot simply call up those ‘dozens’ of other companies and ask them to shift their existing production over to making the mRNA vaccines.” Notably, the recent Defense Production Act prioritization of filters for Pfizer seems aimed at aiding this step in production.

This bulk vaccine has to then be combined with stabilizing ingredients, poured into vials under sterile conditions, packaged, and shipped. This “fill and finish” stage has emerged as another bottleneck.

Designing an assembly line to fill and finish takes a long time for any new vaccine factory, former industry managers told BuzzFeed News, because it requires extensive safety testing for each step. Introducing any changes to the line, or adding lines at other facilities, requires that same lengthy testing. Moderna's move to pack more doses into the same number of vials on its filling lines, rather than just filling more vials with the original number of doses at somebody else’s factory, is a way around this problem.

We can open up some of the bottlenecks — but need to be careful.

Between April and June last year, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, based in Norway, conducted a survey of vaccine manufacturers, finding a worldwide capacity to make 2 billion to 4 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines by the end of 2021. Industries have mobilized to produce more doses since then, but that will fall far short of what’s needed to vaccinate the world’s 7.7 billion people.

For decades, vaccines didn’t bring the profits that other drugs did, driving the pharmaceutical industry to shutter factories and exit the business. In the last decade, there has been a revival, but industrial expertise is still lagging. “We can’t be harsh on the industry and their profits but also expect them to turn on the dime on their own time to have lots of extra capacity available,” said Robinson.

For this reason, it may make more sense to augment existing factories to boost production of mRNA vaccines while looking for outside facilities to shore up the supply of more traditional shots still being tested against the coronavirus.

But worldwide shortages of raw materials and specialized equipment should make Biden’s White House ultracautious about stepping in with the Defense Production Act to prioritize materials that other countries need to make their vaccines, Robinson said. They might retaliate by blocking US imports of other supplies made in their country, with the end result that fewer vaccines are made everywhere.

“Nobody’s supply chain is 100% domestic for vaccine raw materials,” Robinson said. Muscling one’s way into pharmaceutical supply chains to prioritize raw materials for vaccines could also mean that other vital medicines go unmade.

Any move to upgrade production in manufacturing has to be checked for unintended consequences downstream or upstream. The US might prioritize Pfizer or Moderna getting first dibs on lipids, for example, but that could slow production of other drugs that use them, like those for multiple sclerosis or cancer. Adding more machines to combine the lipids with the mRNA might require halting production at a factory while they are installed, causing a temporary dip in supply.

For those reasons, vaccines that will arrive later and don’t rely on mRNA, such as Johnson & Johnson’s, might benefit from using outside manufacturers to scale up production. That vaccine is based on an approach more manufacturers have experience with, using a harmless cold virus that is equipped with the genes for coronavirus spikes. The vaccine showed 66% effectiveness in reducing COVID-19 cases in worldwide trials, according to clinical trial data announced last month. Last week, Johnson & Johnson applied for authorization from the FDA, which would make it the third vaccine available in the US.

“These first vaccines aren’t going to be the answer for everyone,” Robinson said.

On top of all this, Anthony Fauci, chief of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said on Wednesday that vaccine makers are weighing how to change their shots to address dangerous new coronavirus mutants. A variant found in South Africa, which has been seen in a few US cases, is of particular concern, he said, although vaccines still show efficacy against the virus in limiting severe disease. Changing existing vaccines could add an extra level of complexity if manufacturers decide to collaborate.

In a January interview with BuzzFeed News, Pfizer vaccine chief scientist Philip Dormitzer expressed confidence in the company’s ability to swiftly retool RNA vaccines if a coronavirus variant resistant to current vaccines emerged. Rather than undergoing exhaustive clinical trials for brand-new shots, Dormitzer was hopeful that those retrofitted vaccines could be released more like seasonal flu shots.

“The bottom line is that we have vaccines that work well,” Fauci said. ”Obviously what we're going to be planning, if necessary, is to upgrade vaccines in the future.” ●

UPDATE

This story has been updated to include the FDA's decision on Friday to allow Moderna to fill its vials with 14 doses instead of 10.