In the summer of 2004, a 15-year-old boy, needy and eager for attention, was driven down a road that stretched through the endless flatlands of Maryland’s eastern shore. The boy, known in court records as R.R., arrived at a dirt driveway, where a sign on top of a wooden post announced Last Chance Farm.

Four separate couples lived at Last Chance Farm. All were related to one another and all earned money taking care of troubled children who had been placed in foster care, including R.R.

But R.R.’s new guardians weren’t directly supervised or paid by the government. They had been signed up as foster parents by a giant corporation called National Mentor Holdings, which, over the last three decades, has turned the field of foster care into a cash cow. At any one time the company has an average of 3,800 children and teenagers in its foster homes in 15 states around the country.

Not long after R.R. arrived, Stephen Merritt, the boy’s new foster father, gave R.R. a beer. Then a cigarette. Soon a joint. When the boy was buzzed, his foster father slipped a hand into his pants to fondle him. Then he performed oral sex on the boy.

R.R. had courage. He told the caseworker overseeing his foster placement what was happening. But R.R.’s caseworker, according to the story R.R. told in court records, took no action. The caseworker worked for Mentor too, and instead of filing charges, or even removing R.R. from danger, the caseworker sent him back to Last Chance Farm. It was only after R.R. complained a second time, according to court documents, that Mentor took him from the home.

And there were more indications of sexual abuse at Last Chance Farm. A separate police investigation involving another child had taken place in 2003. Then another in 2006. A psychotherapist sent a letter to Mentor in 2010, warning of “a huge red flag" about Merritt’s interactions with a child.

Even so, the abuse continued, boy after boy. When the police finally descended in 2011, they found sex toys and lube scattered about and victims who told stories similar to what R.R. had told his Mentor caseworker seven years earlier.

The abuse at Last Chance Farm may have been an extreme event, but Mentor’s blunders in screening, training, and overseeing its foster parents are not. A BuzzFeed News investigation has found that the problems at Mentor are not limited to a few tragic cases but are widespread.

Few states make their evaluations of foster care providers public. But government assessments from three states show that Mentor has had troubling deficiencies in selecting, training, and monitoring its foster parents and foster homes.

At least six healthy children have died in Mentor custody since 2005, including the grisly murder of a 2-year-old in Texas in 2013 whose foster mother swung her body into the ground like an ax, and in nearly all these cases there have been allegations that negligence by Mentor contributed to the deaths. Other children have been sexually or physically abused, sometimes after clear warning signs.

Many former workers say they believe the pressure to squeeze profits out of foster care is part of the problem.

Mentor officials strongly disputed the idea that their company provides substandard care or that the drive for profits hurts children. Dwight Robson, Mentor's chief public strategy and marketing manager, said the company has done an excellent job of protecting and caring for "literally thousands of vulnerable children whose lives we enhanced." He pointed to Maryland, where, in their most recent evaluations, state regulators gave the company high marks.

Indeed, many, probably most, of the company’s foster parents offer stable and loving care. Moreover, a comprehensive view of Mentor is virtually impossible, because America's foster care system is fragmented, administered by states and counties that typically do not share information publicly — or even with each other — often citing child confidentiality.

Still, in many places where statistics were available, Mentor stumbles, a BuzzFeed News analysis shows.

In Texas, Mentor ranks dead last among large foster care providers, based on the number of severe violations found by state inspectors. Over the last two years, Mentor racked up more “high” deficiencies — the worst kind — per home than any other provider with at least 200 homes. Mentor’s rate was 170% above the overall rate among other large providers.

In an interview with BuzzFeed News, Mentor officials contended the high rate could be attributed to the fact that the company has been under greater scrutiny than other providers. So BuzzFeed News calculated the company’s rate of severe problems per inspection, rather than per home, which Mentor agreed was a fairer measure. But that analysis didn’t boost Mentor much at all — it ranked third worst among the 23 providers with at least 100 inspections.

Texas regulators have found more than 100 serious problems over the last two years in Mentor foster homes, including multiple instances of children being slapped, hit with belts, and struck. A baby suffered a broken clavicle after being left unattended on a bed. Another child was taken by his foster parents to an “adult novelty store.” Regulators also found that several children had “inappropriate” sexual contact with members of their foster families. Several others were placed in homes where children were allowed to hit or physically restrain each other.

Mentor also ranks poorly in Georgia, which grades child-placing agencies on a 100-point scale. Mentor has six branches in Georgia. Over the 10 most recent quarters, not one scored an average grade above the median.

In Massachusetts, according to confidential data a children’s rights group garnered in a lawsuit, the company was faulted for 16 cases of abuse and neglect in just one 12-month period between April 2011 and March 2012. That included one fatality in January 2012, the death of a 2-month-old baby, after which a special state investigation found that Mentor foster parents and social workers “were not trained” on safe sleeping practices in caring for infants.

The company said that its scores in Georgia have improved, attaining an average of A- for the most recent quarter. And Mentor’s problems in Massachusetts have been fixed, Robson said. Safety, he said, is “job one.”

He also said that the company performs much better than other foster care operations when it comes to keeping children in stable foster homes where they can thrive, rather than moving them from home to home.

But former Mentor caseworkers and law-enforcement officials said they believe the company sometimes fails children because it is focused on extracting a profit from them.

“You feel the pressure. You have to make those targets,” said a former worker whose name, due to a signed nondisclosure with Mentor, could not be used. “I went there because I care about services for kids. I eventually became a machine that cared about profits. I didn’t care about kids.”

Mentor’s profit margins vary state by state. In Ohio, according to a 2012 spreadsheet obtained by BuzzFeed News, its profit margin, as measured by the common Ebitda method, has been as high as 44%. In Alabama, the document indicates that the margin has hit 31%. That would mean that only 69 cents of every dollar that the state government paid to Mentor was spent on caring for the child and on overhead. Mentor’s overall profit margin, according to its financial disclosures, has been a little over 10%.

Robson denied that the company’s margins ever came close to 31%, let alone 44%, though he declined to say what its margins are, state by state.

Mentor’s foster care business works like this: It receives fees from state and local governments for its services, and it uses some of that money to recruit, screen, and train foster parents, and to pay those parents a daily rate for caring for the children. The money is also used for administrative overhead and to pay the salaries of social workers, therapists, and other staff. But the former workers say that in a bid to increase profits, the company sometimes cuts corners on expensive services that are supposed to ensure the children in its care are safe.

Mentor social workers, for example, may be forced to carry a higher caseload of children than is recommended, sources say. In one affidavit in a court case in Illinois, a Mentor caseworker said she had a caseload of children twice as high as the generally accepted practice.

“Here’s how you cut services: caseloads,” one former Mentor worker told BuzzFeed News. “In therapeutic foster care you are supposed to have 10 kids. So you may have 15 kids. You may have to hire people without licenses because you can get away with it.”

Company officials are quick to dispute any allegations that the quest for profit can cut into the care for children. “We don’t water down services to maintain profits,” insisted the executive chairman, Edward “Ned” Murphy, in an interview. “The idea that we can systematically dilute the quality of services just does not work. We would be out of business.”

In Texas, one of Mentor's most grisly failings prompted a local prosecutor to call for a federal investigation of the company.

In a one-story rented house in Rockdale, in the cattle country northeast of Austin, a 2-year-old girl, blonde and playful, was murdered by her foster mother, Sherill Small, on a hot evening in July 2013.

Alexandria Hill had been taken from her young parents at the age of 1 by the state child welfare agency. The main reasons, Texas officials wrote at the time, were that her parents smoked marijuana around the child and her mother periodically suffered from grand mal seizures. That convinced the state caseworker she couldn’t care for Alexandria alone.

So the little girl ended up in Mentor’s custody. Texas paid Mentor just $39.52 per day for a child of Alexandria’s age, of which $22 went to the foster family. The company was having trouble finding foster parents.

In November 2012, the company placed Alexandria in her first foster home, where, according to confidential records obtained by BuzzFeed News, she appears to have suffered neglect. When that foster family brought the girl to a supervised visit with her birth parents, the parents were shocked to see that her hair was unwashed and uncombed. She was wearing pants stained with dried feces. Both of her legs were bruised.

Her young father complained to the state of Texas, threatening to call the police, and Texas state workers asked Mentor to place the girl in a different home. That’s when Mentor put her in the residence of 53-year-old Small.

Small spent her own childhood in foster care, and in 2012 she applied to Mentor to become a foster parent. Her maternal instincts were so questionable that even her own sisters were astonished when she was approved by Mentor. “She never even raised her own kids,” said Donna Winkler, one of Small’s sisters. “Her mother-in-law raised her kids, the young ones.”

Bill Torrey, the Milam County district attorney who would end up prosecuting Small for murder, said the company’s vetting process was shoddy. “They didn’t do their homework,” he said. “It was horseshit.”

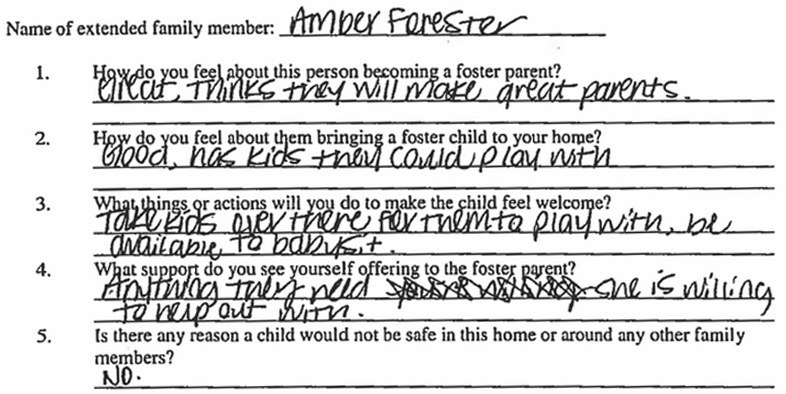

One example of the gaping flaws in Mentor’s background research on Small: Amber Forester, Small’s daughter, said her mother and stepfather “will make great parents,” and that seemed to carry weight. Forester, after all, said she’d be spending time in the home once Small became a foster mother. But Mentor never requested a background check on Forester herself. If they’d asked for one, they would have learned that she had been convicted in 2002 of aggravated kidnapping and robbery after she and an accomplice kidnapped a pregnant convenience store clerk in 2000.

There were other issues. The Mentor “study” of the family shows that Mentor approved Small’s husband, Clemon, as a foster father even though he had been a longtime crack addict: “Mr. Small shared his past struggle with drug addiction, starting in 1980. He said his drug of choice was crack-cocaine.” He said he had last used the drug in 2000.

Mentor didn’t interview Small’s sisters, who said they would have warned the company.

Small was approved and began taking in foster children in September 2012, five in all. By December 2012, prosecutors later found, every one of them had been removed as “failed placements.” Small, according to an internal Mentor document obtained by BuzzFeed News, “reported feeling stressed out, and will express that she is unable to care for the children in the home.” The Mentor document also warns that personnel from the state’s Early Childhood Intervention (ECI) program “felt the children should not be in the home at that time.” It states, “ECI expressed concern about Mrs. Small being very frazzled and not certain what is going on with the children.”

Just a month after that report, in January 2013, little 14-month-old Alexandria Hill, fresh out of her first Mentor foster home, where she had been treated shabbily, was sent to live with the Smalls.

Torrey, the prosecutor, said he was astonished that Mentor would have placed Alexandria there. “How can you justify a report from your people that you apparently don’t read?” he asked. “It’s just a report? What, another piece of paper that goes in the file? No one looks at it? A sixth-grader would have known that you don’t put Alex Hill with these people, in light of Mentor’s own records!”

Mentor’s records, obtained as part of the murder case, indicate that Mentor officials claimed Alexandria was initially flourishing with the Smalls. In June officials wrote that Alexandria was “doing well” and that she is “healthy and playful. She enjoys playing with her toys. She loves to watch cartoons.”

But Sherill Small’s sisters, Donna Winkler and Diana Baines, told BuzzFeed News the little girl was treated poorly. Winkler said Small “hated” the girl, while Baines said that when she visited the home, Small kept Alexandria in a barren room on the second floor where she was allowed to hold her teddy bear, and that was it. “She wasn’t hardly allowed to come outside her room at all,” Baines said.

Baines and Winkler said Mentor did conduct inspection visits, but that they were useless because the visits were always prearranged. Small tidied up the home in preparation, they said, and allowed Alexandria to watch TV so she’d be quiet while the Mentor worker was there. Meanwhile, there was another warning sign documented in Mentor’s own records: Alexandria was pulling at her hair so much she was going bald in spots.

On the afternoon of July 29, Baines visited Small’s home. She waved to little Alexandria, who was standing in a room called the “man cave” that had been formed from a renovated garage. Small told her Alexandria was on a time-out, being punished for waking up too early and taking food for herself. Winkler came by too, and heard the same story: The little girl was being punished.

It was later that day, in the evening, when Small and her husband called 911. When emergency workers arrived, the girl wasn’t breathing.

Once she was hospitalized, a doctor found that the back of her skull had received a crushing trauma. Her real parents, Joshua Hill and Mary Sweeney, were notified. According to her grandmother, Diann Hill, it was while Joshua was sitting anguished in the hospital that an official from the state of Texas arrived. The father asked what he should do.

The official answered, according to the girl’s grandmother: “She’s in your custody now. That’s up to you.” The parents agreed to take the little girl off life support, and Alexandria was declared dead on July 31.

Soon, Small admitted to police that she’d been frustrated with the girl, and described how she’d swung her until her head crashed into the floor in what she said was a tragic accident.

“Obviously we made a poor judgment in that case,” said Mentor’s Robson. “And if we could turn back the clock we would.” But he was emphatic that the disasters in the way the company screened Small, and placed Alexandria with her, had nothing to do with an effort to cut costs to increase profits. And he said the company has learned from its mistake and made improvements in its background checks and other procedures.

Torrey, who has a picture of Alexandria Hill in his office, said he is not convinced. Sherill Small was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison, but in his interview with BuzzFeed News, Torrey said that based on what he learned in his investigation, Mentor itself needs to be the subject of a larger probe. “We don’t have a lot of resources in this county, so what I would like to see is someone, an attorney general somewhere, the Department of Justice or a U.S. attorney, someone like that, look at it.”

When Torrey first started investigating the Alexandria Hill case, he was shocked to learn that foster care is a for-profit business. “Money for kids — it’s like a crop, that’s what it is,” he said. “It should not be a business.”

And for most of the last century, it wasn’t. State and local governments, which are largely responsible for children whose parents cannot care for them, often subcontracted the work of placing children in foster homes to nonprofit organizations, including religious groups.

But over the last three decades, for-profit operations have moved into the sphere, with scant public scrutiny. It is a transformation that Mentor has helped drive — and benefited from handsomely — first under the leadership of the company’s founder, Marine Corps veteran E. Byron Hensley, and then under one of its first government partners, Edward “Ned” Murphy, who would later come to run the company.

Hensley, who founded Mentor in 1980 in Boston, said in an interview that he hadn’t started his career intending to work with youth. He was a graduate student in philosophy, but after a rough divorce, he moved to Boston and landed a job running a group home for troubled kids.

Hensley said he quickly became convinced that the teens would do better in private homes than in the dilapidated group home where he was working, and he also figured he could earn a living helping to place them there. He named his organization Mentor, after the wise and nurturing figure in Homer’s The Odyssey who cared for Telemachus, the son of Odysseus.

His chief customer, he says, was the Massachusetts Division of Youth Service, then under the command of Murphy. But within three years, Hensley said, he became convinced a for-profit model would better serve all involved, because it wouldn’t be burdened by the yoke around the neck of so many charities: constantly raising funds from donors.

National Mentor, Inc., a for-profit company, was born.

Within four years, Mentor was also doing business in Ohio and in South Carolina. In 1987, Hensley recalled, he convinced two venture capital firms to invest $700,000. He said he warned them that profits on foster care would be small, just 3–5%, but that was more than made up for by the potential for growth.

The growth was phenomenal. Soon Mentor expanded to Texas, Illinois, North Carolina, and Indiana. By 1997, after some takeovers and corporate restructuring, Hensley said, he left. He said the company he’d founded with $10,000 from the sale of his house in Waltham Mass was then worth $50 million.

In 2001, Mentor was bought by Madison Dearborn, a Chicago-based equity firm with billions under management that specialized in leveraged buyouts. Mentor, Hensley says, began spreading into other ventures in “human services,” including group homes and home care for adults. But its bedrock business remained foster care.

In 2006, the hedge fund Vestar Capital Partners bought out the company, investing $242 million in cash, according to filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Vestar is well-connected in both Republican and Democratic circles. Frederico Pena, a former Clinton Cabinet official, and later a co-chair of the Obama campaign, is a managing director there.

Coming out of the deal, Mentor was burdened with a debt of $520 million. According to SEC filings, 5 cents of every dollar that Mentor made had to go to cover just debt. According to people who worked at Mentor, Vestar has squeezed the company to turn more of a profit. A statement from Vestar said, “We are proud to be associated with an organization that has enhanced the lives of tens of thousands of children and adolescents and adults with disabilities.”

Vestar brought Mentor public last year, and the firm began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the name Civitas Solutions, Inc. It reported $1.2 billion in revenue last year.

In some jurisdictions, such as Illinois and some counties in Pennsylvania, for-profit companies can’t get contracts to run foster care operations directly. Mentor found a way around that, by partnering with nonprofit sister organizations Alliance Human Services and Alliance Children’s Services, both founded by Murphy.

Indeed, the corporate paper trail shows that Alliance group subsumed the original nonprofit Mentor Inc. that Hensley founded in 1980.

Those nonprofits have received contracts in states that bar for-profit foster care operations. And then those nonprofits turn around and hire Mentor’s for-profit arm as a subcontractor to run virtually the whole operation.

In Illinois, for example, Alliance gets paid over $200 per day per child to provide therapeutic foster care to children. But, according to contracts obtained by BuzzFeed News, it has hired Mentor to recruit the foster parents, check their backgrounds, train them, monitor them, and act as social workers for the children.

Mentor’s Robson said that when Alliance was layered into Mentor foster care contracts, it wasn’t a ruse but an effort to make sure federal dollars kept flowing during periods of confusion about whether for-profit operations could get reimbursed. He said state and federal officials knew of the arrangement between Alliance and Mentor. Reached briefly by phone, the president and CEO of Alliance, Mary McCarthy, also defended the contracting, and said, “The reason that we started any of these things were to help states that needed help in getting federal reimbursement.”

Robson said that Mentor does not control Alliance. Still, the two organizations are intertwined at many levels. In addition to Murphy, who founded Alliance and now heads Mentor, another former senior official at Mentor, Doris Davila, is now a vice president at Alliance. In Illinois, Mentor is headquartered in a large office building at 600 Holiday Plaza Drive in Matteson. It’s in Suite 400. Alliance is in Suite 410.

Alliance Children’s Services, which was the charity that subcontracted to Mentor in Texas for 16 years, even reported to the IRS in its nonprofit filings that its books and records were in the custody of the for-profit National Mentor.

If the murder of Alexandria Hill illustrates Mentor’s failures to select appropriate foster parents, the sexual abuse visited on R.R. and other boys over a period of a decade at Last Chance Farm shows the company’s problems training and monitoring foster parents — in this case, even in the face of multiple warning signs.

The first couple on the farm to get certified by Mentor were Stephen Merritt’s father, also called Stephen, and his wife, Carol, in October 1997.

County health inspectors had warned that the place was too run-down for small children, with peeling paint and hazards. Still, Mentor approved the couple.

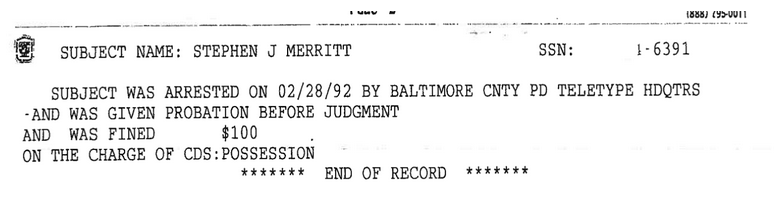

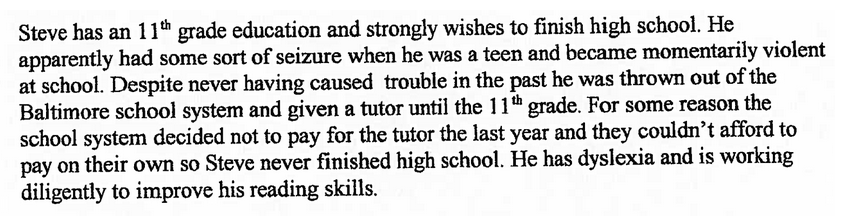

The younger Stephen Merritt, then 28, and his wife, Trudy, signed up with Mentor in 1999 at another house in the same compound. Merritt passed a background check easily. He denied any history of drug use despite clear evidence in his file that he had been arrested for marijuana possession.

He even told the Mentor recruiter that he had been kicked out of high school for throwing a desk at a teacher.

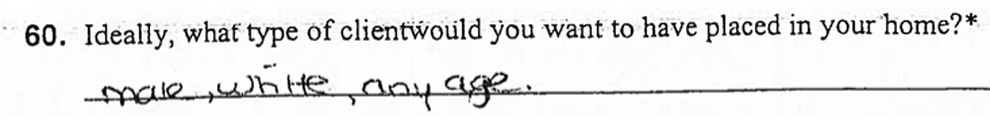

And he specified that they wanted boys, not girls, a fact whose significance only became clear years later. “Male, white, any age” was his answer on the questionnaire.

Other Merritt relatives soon joined the foster business as well, with four separate households taking in children on the sprawling farm.

The state of Maryland required Merritt to complete 20 hours of training a year, a heightened requirement because the boys in his care were considered high-need and were in so-called therapeutic foster care.

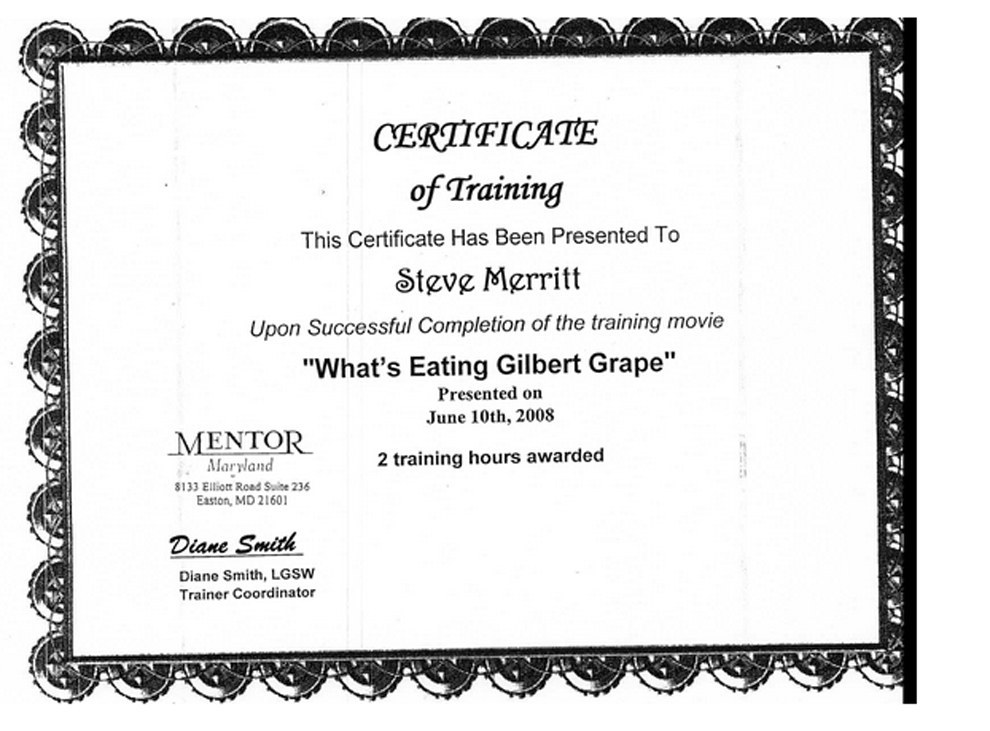

But in practice, that training was hardly rigorous. In 2008, Mentor awarded Merritt two hours' credit — and a fancy certificate — for watching the movie What’s Eating Gilbert Grape. In 2007, Merritt didn’t even have to watch a movie: He got two hours' training, and another certificate, for attending Mentor’s Christmas lunch.

Sarah Magazine, Mentor’s spokesperson, defended the training. “One of the tools we sometimes use are movies to facilitate a discussion,” she said, adding that the portrayal of a troubled family struggling with disabilities make it a popular training film for Mentor and other other foster care organizations.

Meanwhile, in 2003, the police launched an investigation of Merritt at Last Chance Farm, after a 15-year-old foster child said Merritt had unbuckled his own belt while joking about the boy being good with his hands. But the boy recanted later, telling the police Merritt was just joking, and the police said the charge was “unfounded.”

Then, in 2004, R.R. arrived and began getting harassed. As the story, culled from court records, indicates, R.R. told a Mentor caseworker that he was being abused. But since he wasn’t believed, he was put back in Merritt’s custody. After he complained again, he was finally sent to another home. BuzzFeed News could not reach R.R. for comment.

Magazine, the Mentor spokesperson, said she believes R.R. was taken out of the home as soon as he first made abuse allegations.

Still, even after learning of R.R.’s allegations, Mentor kept sending foster children to Last Chance Farm. In retrospect, the company now says, that was a mistake. “Kids should not have been at that home,” said Robson. “We acknowledge that and we accept that.”

In 2006, two years after R.R.’s time at the farm, allegations of wrongdoing bubbled up again. The police learned of a foster child who said he’d been offered marijuana and alcohol at the Merritt farm and had had sex with Merritt. But the police assumed the boy was talking about Merritt's wife. The boy angrily denied it, and told investigators, “You need to get your shit together before you talk to me.” Police ruled the allegations, again, “unfounded.”

And then in 2010, a psychotherapist named Laurie Rockelli warned Mentor about Merritt. One of her patients was a former foster child of Merritt's, and Merritt was texting the boy on topics of a sexual nature. Worried, Rockelli sent a letter in February to Mentor’s operation in Maryland. “I’m writing this letter out of extreme concern,” she wrote.

There’s no evidence that Mentor took any action after Rockelli’s letter. In fact, in March, the month after that letter from the psychotherapist, Mentor gave Trudy and Stephen Merritt an updated foster care license.

Magazine said the company did react to the Rockelli letter: Merritt was told, she said, that texting with former foster children “wasn’t appropriate.”

A year after sending Mentor her warning letter, Rockelli learned the truth about what was happening at Last Chance Farms: Her patient, still troubled, finally admitted he’d been sexually molested by Merritt, his former foster parent. Now Rockelli went to the police.

When they brought Merritt in, he folded under questioning, and fast. In the interrogation, he did say one thing that surprised them: They should go look at what his uncle, Tracy Bayne, who lived at Last Chance Farm as well, was doing with his foster son. Bayne was also abusing a boy. And, police would learn, many years earlier the uncle had molested Stephen Merritt.

The prosecutor in the case, Jamie Dykes, now in private practice as a lawyer, said she doesn’t believe Mentor knew what was going on at the farm. But she said the company should have known — and could easily have found out. Mentor, she said, never made surprise visits to Last Chance Farm. She said that when Mentor caseworkers came, “the children knew when they were going to visit, because they were made to clean the house. Clean the house from top to bottom.”

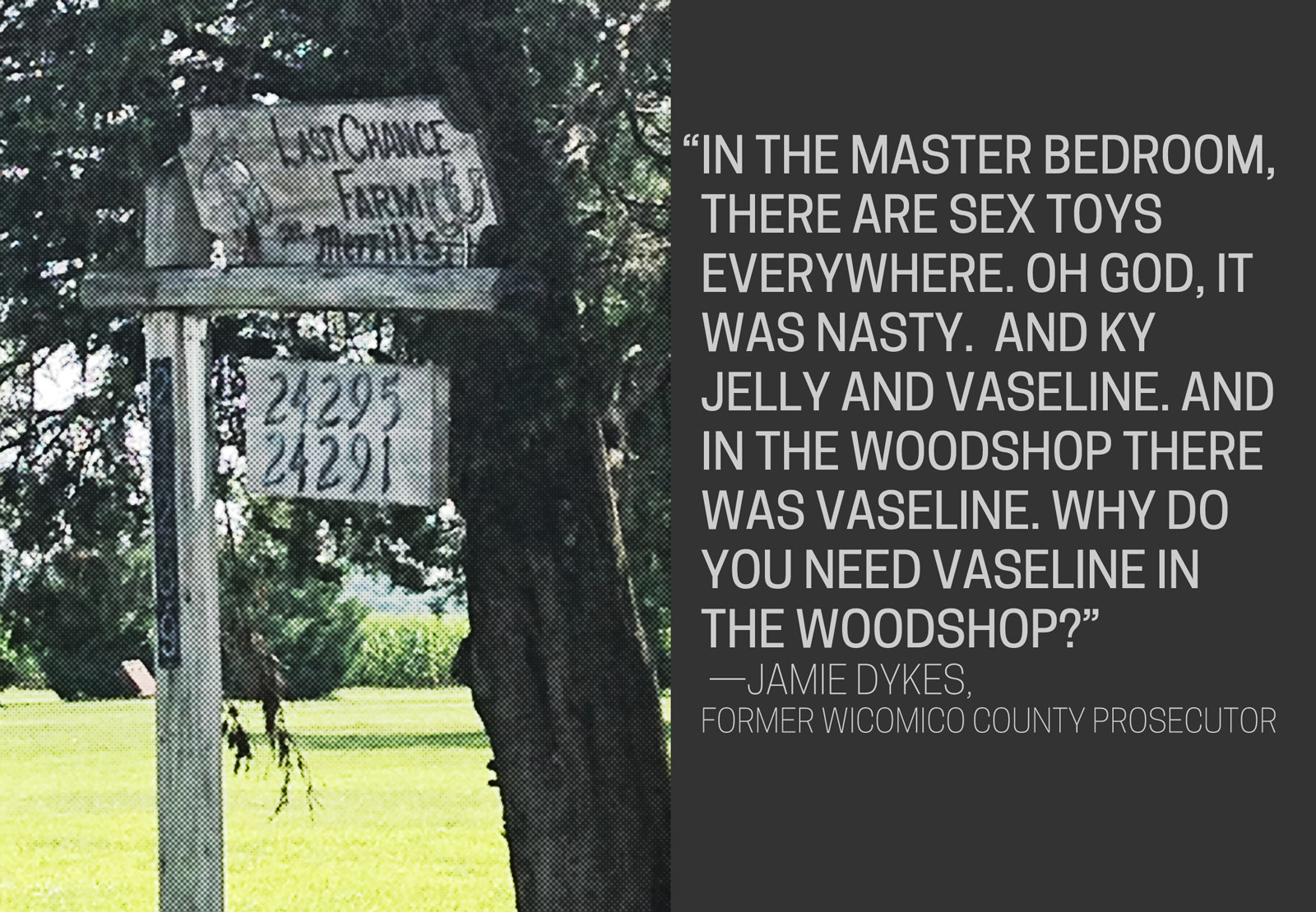

Unannounced visits might have provided a different picture, she said. Dykes recalled that when she served a search warrant there, the scene was “disgusting,” “dirty,” and disturbing.

“In the master bedroom, there are sex toys everywhere," she said. "Oh god, it was nasty. And KY Jelly and Vaseline. And in the woodshop there was Vaseline. Why do you need Vaseline in the woodshop?”

Stephen Merritt pleaded guilty. Merritt’s defense lawyer argued at his sentencing that although Merritt was guilty, Mentor deserved blame too. “The child welfare system sought out the Merritt home methodically and consistently to place these children in their care,” she said. “Unlike Mr. Merritt, the Mentor program does have the cognitive ability to make sound decisions, but because nobody else wanted these children and the Merritt home was a easy scapegoat, they continued to place the children year after year after year, ignoring disclosures of the victims, ignoring all of the warning signs that were there.”

With additional reporting by Talal Ansari.

Alexandria Hill was murdered in July 2013, after she was taken from her parents in November 2012. A previous version of this story said she was murdered "last July," and that she was removed from her parents in 2013.