MORENO VALLEY — The largest bribe the FBI has ever paid to a public official in a sting operation wasn’t to a United States senator or even a state lawmaker. It was to a lowly city councilman in this gritty, unglamorous Los Angeles exurb, where a fifth of the population lives below the poverty line, and local headlines play a steady drumbeat of grim news such as the daytime murder of a grandmother at a gas station.

Councilman Marcelo Co didn’t seem particularly interested in improving the town. Even as he ran for office in 2010, he faced criminal charges for renting out apartments that were slummy and unsafe. Midway through his first term, he was caught on tape taking $2.36 million in cash from an undercover agent he thought was a land developer. Co told the agent that for enough money he would vote “yes” on any land-use plans. “I don’t care if it’s the shittiest can of worms,” Co said.

Despite Moreno Valley’s depressed property values, control over its land is actually worth a fortune. Indeed, nearly every major retailer in the world covets the kind of real estate the city offers: empty acres near freeways and train tracks at the epicenter of one of the largest but least noticed land rushes in America.

This arid flatland, shimmering and indistinct in the heat and smog, is just perfect for warehouses. These are not, however, warehouses as most people think of them. These are massive, futuristic behemoths that have proliferated on a scale seen nowhere else on the continent to usher in goods from Asia to consumers across a vast swath of the United States.

Americans have grown to expect the goods they want delivered to their homes or nearby store shelves within days or hours. But all this two-day shipping, click-to-ship, and get-it-on-your-doorstep-by-noon-tomorrow has come at a price, paid by the people who live in the shadows of the mega-warehouses: lung-stunting, cancer-causing pollution and, in some cases, political corruption.

The underside of our consumer economy can be seen in a tale of two cities, just 20 miles apart. There is Moreno Valley, where developers have shoveled in money to win the political approvals to build new warehouses. And there is Mira Loma, a tiny community already awash in warehouses and suffering some of the worst pollution in America.

“Everyone wants a new flat-screen TV,” said Ed Avol, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine who has spent the last two decades studying the effects of air pollution on children. “Everyone wants new clothing. But nobody thinks about how it got [to them.]”

Moreno Valley and Mira Loma lie in the vast sprawl east of Los Angeles known as the Inland Empire. Three decades ago, the area was a bastion of orange groves, military bases, and light manufacturing. But in recent years, a number of Inland Empire cities, which even many Southern California residents couldn’t locate on a map, have quietly become pivotal to a transformation in the global economy.

More than 40% of all shipping containers imported to the United States enter through the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Most of that cargo then moves through the Inland Empire. It either passes through or stops off at distribution centers serving Amazon, Wal-Mart Stores, Target, Costco, Home Depot, Restoration Hardware, Baskin-Robbins, Nike, Nordstrom, Kraft Foods, Toys ‘R’ Us, Ford, BMW... the list goes on and on.

If you live anywhere in the United States west of about Chicago, and you eat, wear, watch, play, sit on, or drive a product bought retail in recent years, chances are good that it came through this area.

And if you live in the Inland Empire, you’ve watched giant flat-roofed buildings that resemble alien spaceships march across the landscape with a speed some compare to a raging forest fire.

There is now enough industrial space in Riverside and San Bernardino counties — the two counties that make up the Inland Empire — to enclose almost half of Manhattan. Industry experts estimate that the area needs at least 15 million additional square feet every year just to keep pace with demand.

That, in and of itself, might not be so bad for the air. But getting the goods in and out of these warehouses requires trucks and trains. Thousands upon thousands of them, passing through in a ceaseless tide, creating a dull background roar, and contributing to some of the worst pollution in America.

Although air quality overall in Southern California has improved in the last two decades, according to the South Coast Air Quality Management District, the area has had among the nation’s worst ozone pollution almost every single year since 1988 and the worst fine-particulate-matter pollution in Southern California since the agency began measurements in 1999.

The community that epitomizes the pollution warehouses can bring is Mira Loma.

“Our quality of life is in the tubes,” said Gene Proctor, 73, who has lived in Mira Loma Village for 43 years. “I wish people shopping in Tucson, Arizona, in other places, I wish they could see the little kids around here, their respiratory problems.” His great-granddaughter has asthma, and his 3-year-old great-grandson, he said, “coughs like a smoker.”

Population 21,000, Mira Loma is so small and poor it doesn’t have a movie theater, a community center, or even a moderately upscale restaurant. What it does have are 90 warehouses and a whole lot of big rigs: Trucks rumble through 15,000 times every day. In just half an hour on a recent afternoon, 269 trucks passed by the big plate glass window in the front of the Farmer Boys truck stop on Etiwanda Avenue.

That is more than one every seven seconds.

Avol, the professor at the USC Keck School of Medicine, began visiting the town in the early 1990s as part of a study of air pollution and children’s health across Southern California. Back then, he said, researchers chose Mira Loma because it sits at the “end of the tailpipe” of the Los Angeles basin, meaning the prevailing winds off the Pacific Ocean blow L.A.’s infamous smog east until much of it arrives in Mira Loma. So it was rural yet had a lot of ozone and smog. Other places in the study, such as Santa Barbara and Long Beach, were picked because they were thought to boast clean air or because they were in industrial areas.

When the study began, Mira Loma residents complained to researchers about the smell of dairy cows, herds of which clustered on vast pastures and cow yards. But in 1987, Riverside county supervisors revamped the general plan for Mira Loma, clearing the way for massive warehouse development.

“In the course of a few years, the dairies disappeared,” and what had been “open pasture became streets and warehouses, lined with trucks,” Avol said. “Mira Loma turned out to be a very interesting place to study.”

The trucks made the already bad air worse, bringing in diesel particulates, very small particles that can enter the lungs and travel to tissues throughout the body. They are associated with asthma, heart disease, neurological problems, and cancer.

In Mira Loma, children were found to be growing up with stunted lungs compared with children living in places with better air. Their lungs were growing at a rate that was 1 to 1.5% slower, Avol said, so that “after their teen years, they were about 10 to 12% lower in lung function than children who had grown up in cleaner places.”

He added: “We have no information at this point that supports the idea that they ever catch up.”

Studies from other Inland Empire communities are also dire. In a neighborhood near the BNSF rail yard in the city of San Bernardino, Loma Linda University researchers found that adults have more respiratory problems, and children alarmingly high rates of asthma, even when compared with other polluted communities.

Warehouse industry officials, along with Barry Wallerstein, the head of the South Coast Air Quality Management District, insist that it is possible to build jumbo warehouses that do not pose a threat to public health. The key, Wallerstein said, is taking steps such as requiring that “clean” trucks service them and ensuring that traffic going in and out does not abut residential areas.

And yet, time and again, records and interviews show, officials failed to consider health impacts when approving warehouses.

A 2002 investigation by the Riverside Press Enterprise, the local paper, examined the dozens of warehouses approved to be built in Mira Loma between 1987 and 2000. County planners couldn’t point to a single one in which they had required a detailed environmental study.

A spokesman for the county said it has “improved environmental protection,” and indeed as lawsuits from environmentalists and disconcerting health studies have piled up, officials across the Inland Empire have been ordering environmental reviews. But that doesn’t mean they turn down developers’ requests for more warehouses.

In 2011, Riverside County officials voted to allow a 1-million-plus-square-foot complex on one of the last pieces of vacant land near Mira Loma Village despite a study that found it would pose health risks to the people living there.

A local environmental group, the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice, sued. California Attorney General Kamala Harris joined the suit on the side of environmentalists.

The two sides reached a settlement last year that allowed development to proceed but required local officials and the developer to make the project "greener," with electric vehicle charging stations and even a potential prohibition on trucks on the road closest to the village.

The settlement also contained a provision that feels ripped from the pages of dystopian fiction: Every home in the village would be offered high-tech air filters so residents could avoid breathing the polluted air right outside their windows.

The warehouse boom has been propelled by two stark factors: poverty and money.

Many of the cities in the Inland Empire, battered particularly badly by the foreclosure crisis, face bleak economic prospects. Just one-fifth of adults over age 25 have a bachelor’s degree. When people are desperate for jobs, thousands of trucks driving through their community every day seems more tolerable.

Then there is the money: Warehouse developers and the retailers that buy or lease from them have it. When they come in, they bring tax revenues to cash-starved local governments.

And developers donate to the political campaigns of politicians who control land-use approvals. Unlike the bribe Councilman Co took, much if not most of the money surely flows through legal channels in the form of campaign contributions. But it’s hard to find an elected official in the Inland Empire who hasn’t benefited significantly, and in some cases overwhelmingly, from development interests.

That was certainly the case in Moreno Valley. Population 200,000, the exurb sits 65 miles from Los Angeles. At the eastern edge of town, houses peter out into a dusty brown expanse, stretching to the horizon.

The flat land, right by a freeway, is the site of developer Iddo Beneevi’s audacious plan to build what may well be the nation’s largest warehouse complex, a 41-million-square-foot colossus equivalent to 700 football fields called The World Logistics Center.

Long before the undercover FBI operative bribed Councilman Co (and then arrested him), Benzeevi methodically bought land — the city estimates he owns or controls about half the developable land in town — and helped build a political machine in this city.

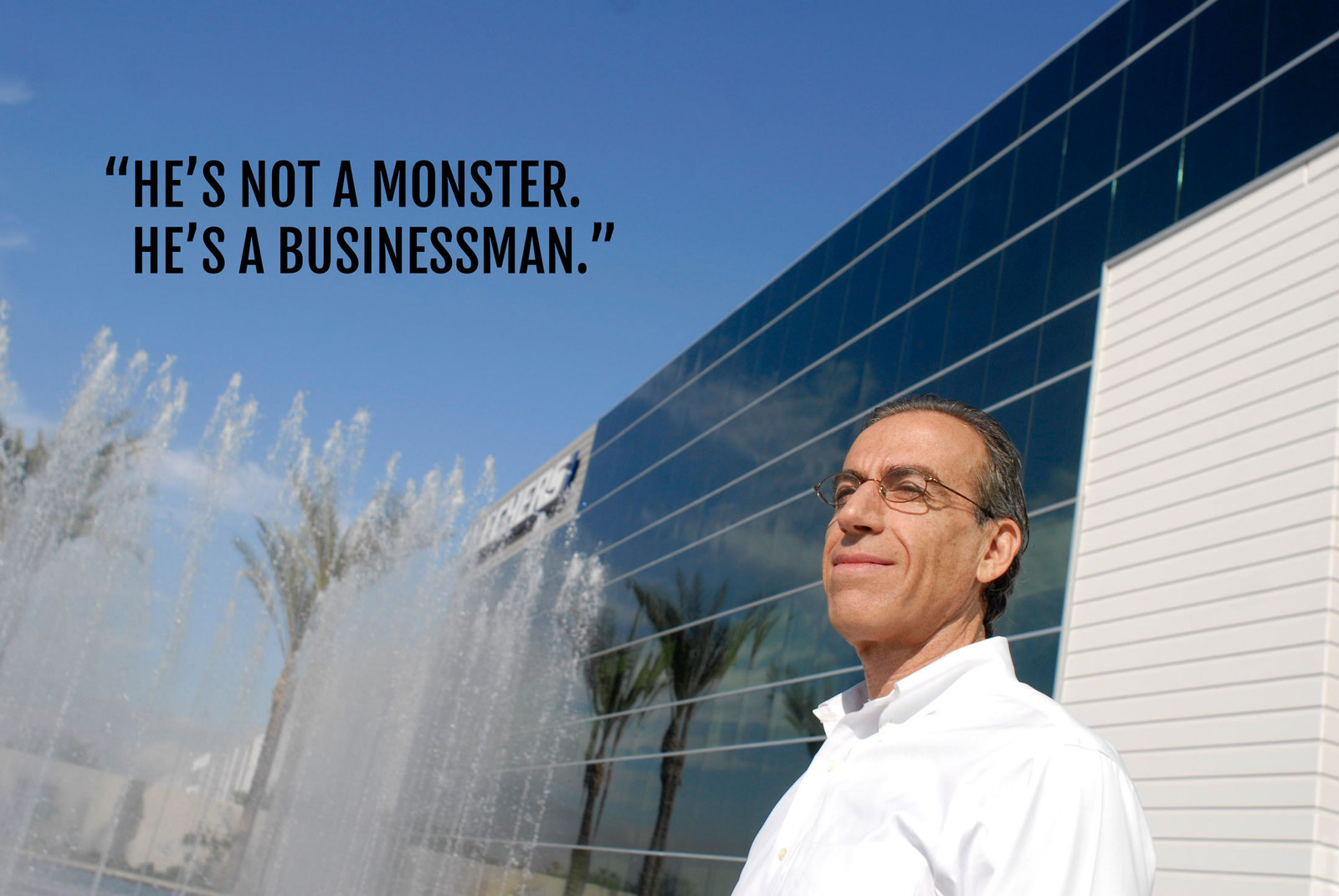

Benzeevi, as he will tell just about anyone who asks and even some who don’t, believes that “the logistics industry” is the inevitable next step in the evolution of human economic development, the end of a line of progress that leads from agrarian society to the great colonial empires to Apple, which, he claimed, can be seen as just a really cool logistics company.

So far, he acknowledged, Moreno Valley has not been a hotbed of economic innovation. But with his help, he insisted, the city can put itself at the center of world commerce.

Benzeevi has an exquisitely courteous manner, even with those who disagree with him, and a fancier style of dress — suits or pressed shirts — than that favored by most who frequent Moreno Valley City Hall. His long-winded fervor on the benefits of the logistics economy is so well known it is something of a joke in town.

But until fairly recently his focus, like that of so many other developers, was on high-end homes that would rise up from the dry scrub as they had in so many other Inland Empire communities before the housing crash.

In 2005, Benzeevi, reportedly working with Florida-based developer Jules Trump (no relation to the Donald), won approvals for “Aquabella,” an upscale community that would feature estates built around artificial lakes — “real resort living, without the hotel,” Benzeevi told one publication.

He even helped convince the Moreno Valley City Council to rename the part of the city that would include the Aquabella community to “Rancho Belago” — the fact that “Belago” is not a word in English, Spanish, Italian, or any other common language didn’t deter anyone, nor did one resident’s complaint that it sounded “goofy” and “like a casino from Las Vegas.”

Rancho Belago signs were eventually put up all over the eastern end of town — although they were modified slightly from the original design after the city of Beverly Hills complained that they looked an awful lot like their iconic town signs. They still look very similar.

The grand project, designed to have “all the charm of an Italian Renaissance village,” was never built. The housing market buckled and crashed, and around six years ago Benzeevi and Trump swiveled to warehouses.

It is easy to understand why. Appetite for warehouse space in the Inland Empire is so voracious that it’s almost sure money — if one can get the land-use approvals and permissions to build.

“It takes forever to get it approved” in California, said Kim Snyder, president of the southwest region for San Francisco-based Prologis, one of the world’s largest developers of distribution centers. “And then sometimes you get sued twice along the way because of some environmental group that contends the wild bunnies won’t have a place to go, or the desert kangaroo or the burrowing owl or what have you.”

For a retailer that needs space quickly, embarking on such a tortuous approval process can make little sense.

So, in contrast to much of the rest of the country, warehouses in the Inland Empire tend to be built on spec, meaning that land developers such as Benzeevi build them and then find companies to rent them — which has never been easier because the gap between supply and demand has never been greater. In just the first eight months of this year, industry experts said, companies snapped up 15 million square feet of warehouse space.

Basically, the business boils down to this: Get approval to build, then watch the profits roll in. Several industry experts estimate that profit margins are consistently in the high teens.

In that context, a developer might like to have as much influence over the land use process as possible.

Even before he turned his focus to warehouses, Benzeevi had been cultivating Moreno Valley’s city council members, lunching with some often, three of them said, at town favorites such as Chili’s and Olive Garden.

Benzeevi also ramped up his Moreno Valley political contributions. Way up. And he did not hesitate to pour money into campaigns against those who questioned his new plans.

“It’s a sad state of affairs that money can practically buy a city,” said former Councilman Frank West. Records show that a Benzeevi-backed political action committee spent more than $60,000 against West and for his opponent. West said he had disappointed Benzeevi by surveying his constituents about whether they wanted a mega-warehouse in their neighborhood. West posed the question as the shoe company Skechers’ national distribution center, developed by Benzeevi, came before the council.

Benzeevi said that he dumped money into the 2008 campaign because the town was “stagnating” and to counter “myths.” Residents, he said, had grown weary of West “cashing in at City Hall while little if anything was happening in Moreno Valley, except for rising crime.”

“We participate in our American democratic process,” he declared, and “the voters make the choices.”

West lost the election. Those still on the council, he said, could hardly miss the point: “If there wasn’t total compliance with Benzeevi’s plan, he had the resources to remove you.”

The Skechers warehouse was approved, and then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger came to the 2010 groundbreaking. The governor mused out loud that he wished Skechers would “create some maybe alligator cowboy boot running shoes.”

The warehouse, which city officials touted as the largest certified green building of its kind in the United States, is more than half a mile long.

In 2008 alone, campaign finance records show that one of Benzeevi’s companies, Highland Fairview, donated or loaned more than $260,000 to local races that, for years before his arrival on the scene, had been won with far lower expenditures. Another big contributor was a land broker close to Benzeevi, Jerome Stephens, who kicked in more than $100,000.

The men did not give their money directly to candidates. Instead, they donated it to a political action committee. In the close-knit ways of small-town politics, that committee had multiple connections to city power brokers.

Its treasurer was a lawyer in town named Michael Geller, who sat on the city’s planning commission and who shared a law practice with Moreno Valley City Councilman Richard Stewart, a proponent of the Skechers project.

Their firm represented people who had complaints against car dealers and also did debt collection for one dealer, Raceway Ford of Riverside. At one point, the law firm rented an office suite at Raceway.

Things even got more entwined. In 2008, as the real estate market headed steeply down, the general manager of Raceway Ford, Tom Owings, sold his four-bedroom, three-and-a-half-bathroom home with a pool and spa in the more upscale community of Redlands and moved into a rental house at the edge of the town in Moreno Valley.

Less than two years later, he was appointed to the planning commission, and in 2012, with the aid of campaign contributions from Benzeevi’s ally Stephens, he was elected to the city council. He also received $10,000 from Skechers, which was later fined $2,400 by the California Fair Political Practices Commission for improperly failing to report that and other contributions.

Owings told BuzzFeed News that he sought political office because he believed he could “improve the city’s financial position and make it a better place to live.”

But moving from a grand home in Redlands to a rental in Moreno Valley was notable to some in town, because that is not the usual trajectory for those not in economic distress. And Owings appeared to be doing just fine. According to a financial disclosure form he filed covering the year 2012, Owings had various streams of income including a salary of more than $100,000 from Raceway Ford. He also held between $100,000 and $1 million in various investments.

Owings said he changed his residence because his grandchildren, who had been living with him, moved away, and his house in Redlands was too big. He also wanted to sell it before the housing market crashed even further, he said, and Moreno Valley was closer to his office.

“Snobbish” is how he described people who questioned his move. “People in Moreno Valley are like the people I grew up with, and I feel more comfortable in Moreno Valley,” he said.

Last year, Owings became mayor of Moreno Valley, a position that rotates among council members.

The former car salesman, who looks a bit like an off-duty Santa Claus and is often seen in the company of his golden retriever Shiloh, quickly became known for his snappish temper and habit of berating people who disagreed with him.

Owings said that he wasn’t beholden to Benzeevi and acted independently of him. But he was viewed as a staunch ally of Benzeevi’s, a perception that was fed not only by his voting record but also by statements attacking critics of the World Logistics Center.

Other council members appeared to be converts to Benzeevi’s vision of transforming Moreno Valley into warehouse central. Councilman Jesse Molina, who had received campaign donations from the Benzeevi-funded political action committee, told the Chamber of Commerce in 2012 that he had dreamed of the World Logistics Center his entire life. (Later, he said he meant that he dreamed of a vision for that part of town.)

Co, the councilman caught on camera taking money from the FBI, was also often supportive of Benzeevi, although in private he could be less than complimentary about development projects to which he intended to give his vote. During a taped conversation with the undercover FBI agent in the spring of 2012, he confided that he had promised a developer “he would always vote ‘yes’ on the developer’s projects even if it was a ‘pissing can.’” The federal affidavit does not identify the developer.

Benzeevi himself said the humungous World Logistics Center represents a chance for Moreno Valley to escape poverty and the long commutes so many residents must make because there are so few jobs in town.

“Moreno Valley has a historic opportunity,” he said in an interview with BuzzFeed News. Life for many of its citizens, he said, is difficult, buffeted by low-paying jobs, endless hours on the freeway, and a choice between making ends meet and paying proper attention to children who must be left alone for hours on end while their parents commute.

The World Logistics Center, he said, would solve many of those problems. He projects it would create 20,000 permanent jobs and another 13,000 construction jobs, and that it would be the largest “sustainable” development in the United States.

Meanwhile, top city officials had been pressuring staff to push through approvals for Benzeevi’s projects, even though some of his plans violated the city’s building code procedures, according to a lawsuit filed last year by three former city staffers.

Those employees claimed they were also under pressure to go easy on a criminal code enforcement case the city had filed against Councilman Co before he won office. His properties had multiple troubles. For example, he rented out an illegally converted garage to not one, but two families with children. After a child was injured in that garage in 2010, building inspectors found a host of problems including dangerous wiring and substandard construction. The lawyer in charge of his defense in the code enforcement case was none other than Geller, the treasurer for the Benzeevi-backed political action committee.

Outside city hall, many residents were also growing restive, especially after an environmental study estimated that truck traffic associated with Benzeevi’s World Logistics Center would lead to a significantly increased cancer risk for people living as far as 20 miles away. (Benzeevi told BuzzFeed News “we have been working diligently” to improve the project, and “judgment should be reserved” until the final environmental review.)

Some were also angry that the Skechers project, which backers had said could create 2,500 new jobs, in fact employed only about 600 — and many of those were people who had been relocated from the company’s old warehouse in a neighboring city.

Last month Robotics Business Review hailed the Skechers warehouse as being at “the vanguard” in using new technologies that rely on robots and automation instead of workers for much of the labor within its smooth, white walls. The article noted that the new technologies allowed the company to cut its staffing by nearly 75%.

Asked about those figures and other matters, Lauren Dutko, public relations manager for the company said in an email: “Skechers has no comment for the story.”

Benzeevi called complaints about the number of jobs at Skechers “another attempt to disparage us based on lies and misrepresentations.” He said there were 1,000 jobs projected at the Skechers warehouse and 2,500 in total at the development, which includes two approved but not-yet-built offices.

Around the Inland Empire, some have also begun to question the quality of warehouse jobs. Inland Empire economist John Husing, a consultant to local governments and businesses, said research shows that the median income in the industry is nearly $44,000 — one of the few routes to the middle class in the region for those without a college degree. Many warehouse developers and municipal economic development officials agree with that assessment. But some researchers argue that this rosy analysis doesn’t include contractors and temp workers, who make up a large portion of warehouse workers. Advocates maintain that many of these jobs are low-paid and unsafe, trapping workers in poverty with little chance of advancement, or running them ragged until they get injured.

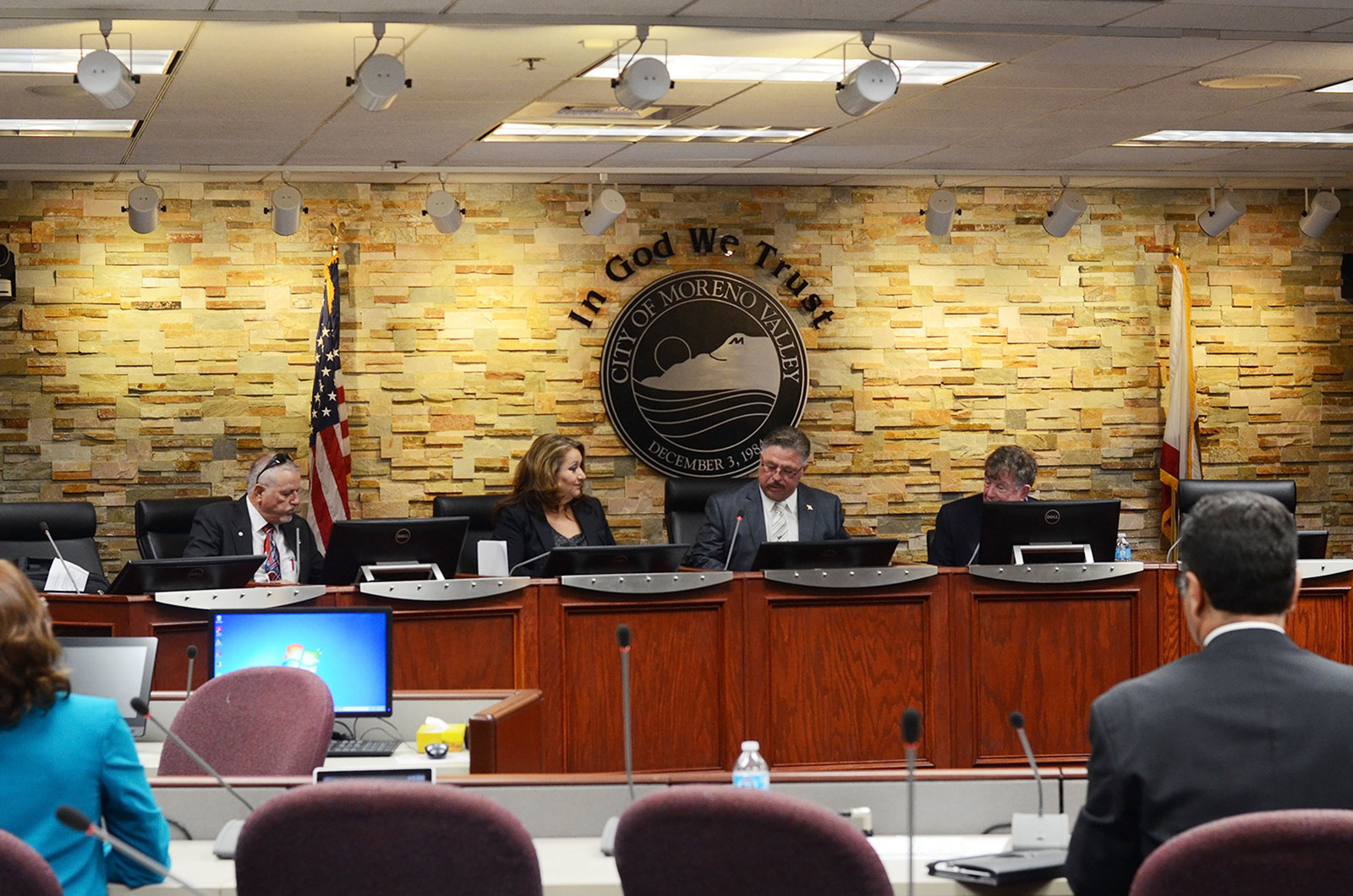

This was the context, when, in April of last year, boosters and bashers of Benzeevi’s World Logistics Center once again hustled into the gleaming Moreno Valley City Council chambers. Speakers pointed to Mira Loma as a cautionary tale and spoke darkly of air pollution and truck traffic and quality of life destroyed.

Mayor Owings listened to it all. But then he exploded into a tirade that made headlines.

“I’m not gonna let these people continue to lecture us every damn council meeting on how our city sucks,” he said. “I want to make it clear for the record that these people do not speak for the citizens of the city … The people who mind their business, the people who pay their bills ... maintain their jobs.”

The mayor also said that he was “tired of the false allegations” and “the innuendo” from “smear merchants” who “degrade the people who are trying to do good.”

One week later, the FBI and the Riverside County district attorney, working together on a “corruption task force,” raided the homes of council members, along with Benzeevi’s office.

Federal officials also subpoenaed tens of thousands of pages of documents from the city, including all records pertaining to Benzeevi’s company, as well as other development projects.

Six months later, in November, authorities revealed that Co had been caught on tape negotiating cash payments from an undercover FBI agent and had agreed to plead guilty to taking a bribe.

The FBI also released a photo of Co sitting in front of a table piled high with cash. The FBI believes it is the largest bribe ever paid to a public official in an undercover operation.

The length of time between the on-camera bribe, in January 2013, and the revelation of the criminal charges led many to speculate that Co had spent much of the previous year running around town wearing a wire. Co’s attorney, Brian Newman, declined to comment.

Council members took turns declaring their innocence. Owings issued a press release calling himself “a reform mayor” and declaring, “I welcome this probe.” He showed up uninvited at the federal grand jury to offer testimony.

For his part, Stewart claims that his house was not really searched. He said he had begun working with the investigators about three weeks before the raids, after agents showed up at his house and told him he had once been a target but no longer was. Stewart said he thinks he stopped being a target because he had voted against Benzeevi’s wishes on a few occasions.

“I’m not going to reveal any details of what I did with the agents, but let’s say it’s sort of like what is in the movies,” Stewart said.

Benzeevi said he had little knowledge of the investigation but said he had been told “by both the District Attorney’s office and the Department of Justice that we are not the subject” of the investigation.

FBI officials declined to comment. No other charges have been filed.

Geller, the attorney who was the treasurer of the political action committee, said, “They didn’t find anything because there’s nothing to find.”

He added, “People seem to think [the council members] would never have voted for it but for [Benzeevi’s money], but these things are all good for the city. It’s not like they are building a toxic waste site or a slaughterhouse in the middle of the city. All these people saying how terrible it is, they are people who don’t need a job.”

Still, in the wake of the FBI raids and Co’s guilty plea, the town descended into political uproar.

Co resigned last year, after being charged in another, unrelated, criminal case involving embezzling social service funds intended for the care of his own ailing mother.

Mayor Owings was recalled from office in June.

Yxstian Gutierrez, who was hastily appointed to replace Co on the city council, was recently found by a judge to not to meet residency requirements for his district and was removed from office. There was recently a blank spot on the wall of City Hall where his portrait used to hang.

Another Benzeevi-supported council member, Victoria Baca, faces a recall election in November.

Last year, Benzeevi’s Highland Fairview company spent nearly $300,000 fighting the recall campaigns, which he called “an abuse of the political process by a small group of bullies that were declaring people corrupt when those individuals had not even been charged with anything.” Benzeevi said his money was spent on “voter education.”

Molina, the councilman who made it into the local paper saying he had dreamed about the World Logistics Center his whole life, now says he isn’t sure how he will vote. He also said that Benzeevi hadn’t acted any differently from any other developer. “He’s not a monster,” Molina said. “He’s a businessman.”

None of the turmoil, however, has killed developers’ appetite for warehouse space in Moreno Valley.

Amazon.com recently opened a “fulfillment center” on the south side of town, and has another project under construction immediately across the street. Decker Shoes plans to locate its North American distribution center in town. Procter & Gamble recently opened a distribution center, and Aldi, the German supermarket chain that is a sister company to Trader Joe’s, recently began construction on a warehouse.

Prologis’ Snyder said he believes that Moreno Valley, after a period of chaos, is “back on track.” But he added: “That was one of the most messed up cities we’ve encountered in a long time.” Prologis is interested in two more projects in the city.

Benzeevi’s World Logistics Center, which would dwarf them all, still faces a vote before the City Council.

As residents in Moreno Valley debated the future of warehouses, residents in Mira Loma Village woke up one Saturday in July to a radical response to warehouse pollution.

On that blazing Saturday, workers from the Swiss company IQAir descended on the scruffy streets with pastries, sandwiches, bottles of water — and air filters.

Some of the residents eyed the workers with suspicion and refused to let them in, but when technicians reached Adela Ochoa’s perfectly kept house, with a bench out front under a tree, the family opened the door and watched as they set up the air purifiers in the living room.

“We know it’s a problem,” Ochoa said of the air. “We feel it in our bodies.”

Still, her grandson works in a warehouse, as does her daughter. They need those jobs.

“If you talk about environmental consequences [of warehouses], one of the things you must do is talk about the environmental consequences of poverty,” said Husing, the economist. “The health consequences of poverty are far greater.”

Down the block from the Ochoas, a gaggle of VIPs, including two local city council members, crowded into Juan and Elvia Rodelo’s modest home to witness the air filters being installed.

The couple, who are in their fifties and speak mostly Spanish, flashed polite but uneasy smiles as their house filled up with strangers.

Less than 10 minutes later, the whole group filed back out, leaving the Rodelos looking a bit stunned.

As he walked out the door, Mayor Pro-Tem Michael Goodland smiled at the couple and said, “Enjoy the clean air.”

Watch a narrated slide show on how the way we shop has transformed the Inland Empire