The grounds of St. Mary’s Cemetery in Lynn, Massachusetts, slope up to the southwest in terraced sections bordered by a mossy stone wall. Tucked toward the top of the rise is a small section where they bury babies. Tiny graves, each about 24 inches wide, are lined up together.

In one row, the third baby grave from the left could be mistaken for a gap between graves, a break in the line, because it is unmarked and has no headstone. Still, there is a homemade cross pounded into the ground: two pieces of wood nailed together. The white paint is fading.

And though there is no name there, in this ground a little baby girl, who died in January 2012, is buried. The baby died eight days after she was put in the care of a giant corporation, the nation’s biggest for-profit foster care provider, National Mentor Holdings. It’s a company that has a troubled record, as a recent BuzzFeed News investigation showed, and it operates thousands of foster homes nationwide, 500 of them in Massachusetts.

For years, the state child welfare agency would try to keep secret the facts of the baby’s death — even her name.

This is that baby’s story, drawn from confidential state documents and interviews.

The infant girl was healthy, and she was just under 2 months old when the state of Massachusetts placed her with Mentor. She had brown eyes, and her hair had not yet begun to grow, just a bit of brown fuzz. She was a fussy infant who was content only if she was snuggled in someone’s arms. The state child welfare bureaucracy had taken her from her parents, because the couple were homeless and indigent, and they had criminal records for serious violence.

That winter day, the baby was brought upstairs to the second floor of a yellow clapboard building on Mason Street in Beverly, Massachusetts. In that home lived the foster parents, whom Mentor had selected, trained, and managed.

But there was a glaring safety problem. For decades, public service campaigns in the U.S. have drilled it into to parents, health care professionals, and child-care workers that the leading cause of death in infants is SIDS, Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

The most effective prevention is painfully simple: Put babies to sleep on their backs, and keep loose blankets and pillows out of their cribs so they don’t overheat or suffocate.

The looming danger was also painfully simple: National Mentor, the company that put the baby girl there in that home, had never taught the foster parents about safe sleeping practices for babies.

As BuzzFeed News has previously reported, there have been at least six deaths of otherwise healthy infants and children in Mentor foster homes nationwide in the last 10 years. Children in Mentor’s care have died in Texas, Pennsylvania, and Florida. There have been cases of long-term, serial sexual abuse, and other violence. Investigators in Illinois found “a culture of incompetence” at the company. Authorities in Texas have found widespread problems with Mentor’s foster care operations.

Mentor, which trades on the New York Stock exchange as Civitas Solutions, Inc., reported $1.2 billion in revenue last year. Some former employees contend that pressure for profits has made the company cut corners on care, a charge Mentor denies.

But the case of the two-month-old baby girl in Massachusetts, buried in the unmarked grave, stands apart. That’s because of the lengths that the state Department of Children and Families has gone to keep the circumstances of her death secret.

There were official investigations done, though they were kept from the public. One state agency found “serious violations of child placement regulations” by National Mentor. The company was getting paid $50.94 per day as a fee in addition to what it paid the foster parents, but it never once sent anyone to the home to check on the baby after she was dropped off. Nor did the company get the baby’s medical records to prepare the parents for any potential problems.

And an early investigation by the state agency that actually took the baby from her real parents, the Department of Children and Families, ruled that there had been “neglect” in the death. “The DCF Special Investigations Unit supported the allegations of neglect and death” by the foster father, the report said. An investigator wrote that “it is likely her death was related to the unsafe sleeping conditions.” The father was never charged with criminal neglect.

Although the state did not require Mentor to teach its foster parents how they could avoid SIDS, the investigators wrote that “the management staff at Mentor hold some degree of responsibility for failing to train their foster parents around what constitutes a safe sleep environment.”

By “neglect,” the report meant that the foster father working for Mentor hadn’t provided the baby minimal standards of care. The neglect finding had other ramifications: Federal law encourages states to publicly disclose child deaths resulting from “abuse or neglect.” And without “abuse or neglect” findings, Massachusetts state officials say information must be withheld from the public.

The baby’s real parents, homeless and impoverished, told BuzzFeed News they were never told about the possible neglect of their daughter. Nor, they said, were they told that it was a huge private company, contracted by the state, that was responsible for her. Or that the most elementary and well-known safe infant sleep practices were violated.

That “neglect” finding stood hidden for two and a half years, until BuzzFeed News started asking the state of Massachusetts about it. It was only then that a top official in the state child welfare agency formally reversed the finding, ruling that there was no neglect in the death of the little girl after all, in spite of the way she was put to sleep, and in spite of Mentor’s violations of its own protocols and state rules.

And up until last week, three and a half years after the girl’s short life ended, the agency maintained that it was allowed to keep almost everything about her a secret.

The girl was born Nov. 16, 2011, at Boston Medical Center. She was a big baby at 8 pounds, 9 ounces. The hospital workers put a stethoscope to her chest to listen to her heartbeat, gently felt her tiny arms and legs to gauge her muscle tone, and monitored her breathing. It was all part of the standard Apgar test, which measures a newborn’s health. She scored a strong and healthy 9, just shy of a perfect 10.

Still, she was born to heartbreaking circumstances. The mother, who had alcohol and drug problems, according to government reports, had another daughter who had been taken from her by the state, after nine previous run-ins with the child protection agency. And during the little baby’s pregnancy, records allege the mother tested positive for opiates, oxycodone, and other tranquilizers but was clean when she gave birth, and the baby was as well. Speaking on condition of anonymity, the mother denied using illegal drugs while pregnant.

Randell Brown, the baby’s father, told BuzzFeed News he himself grew up in group homes. He’s been jailed several times for assault, once involving a knife. In an interview at a homeless shelter in Cambridge, he said his only source of income was Social Security disability, and he acknowledged the couple wouldn’t have been able to raise the girl on that.

“I’m not denying the fact that DCF took her to be safe,” he said. Brown remembered the first night his daughter was born, when he stayed in the recovery room. The baby wouldn’t sleep. “She was crying so I picked her up and laid on my back, and she slept. I stayed overnight, and she slept right next to me.”

Records show that a week after she was born, DCF workers took the baby from the hospital and put her into her first foster home. This one was overseen by the state itself, and for a while that worked well. But the strain was too great. That foster mother said she couldn’t take care of an infant because she had too many other children in the home.

Still, she wrote up her experiences, apparently with love and humor, in a letter that was meant to go to whoever took care of the baby next. The girl was “particularly fretful” in the evening, the woman wrote. In the baby’s “perfect world,” the foster mother continued, “she would like to be carried around and held all day.” But there was no perfect world. Her real parents were allowed to visit her just once a week, and no one in the system had the time to hold and comfort the baby as much as she liked.

So the second Friday of January, a state worker took the letter and the baby. First, the infant got to see her birth parents, by now living in a nearby shelter together. They held her and calmed her.

Then the state worker drove the baby to the Mentor foster home in Beverly, a working-class city just north of Boston, on the water. The home, three stories, was on a quiet street in the center of town.

In 2012, in Massachusetts, Mentor made $17.5 million, according to a DCF spokesperson. The firm was getting paid just over $100 per day for each child to provide expensive and specialized homes, where children receive therapeutic care. $50 of that would go to the foster parents themselves, who operated as subcontractors to Mentor.

But after that first day, no one from Mentor showed up to check up on the baby girl for more than a week, in violation of Mentor’s own policies. The firm’s supervisor was going to assign a “coordinator” — a kind of social worker — whose job would be to meet with the baby and the foster parents. But the supervisor didn’t talk to the coordinator until a week had passed, according to a state investigation, and did so only when the two ran into each other near a copy machine.

Safe sleeping practices may sound pro-forma, but they are not. “A safe sleep environment is one of the most important things you can do to protect your child in the first year of life,” said Dr. Linda Fu, a pediatrician at Children’s National Health System. “It’s not something that can be taken lightly.”

On a Saturday, the eighth day that the baby was at the Mentor foster home, the snow fell steadily for hours, the first snowstorm of the winter. Francisco Bloise was at home with the baby and did his best to help her sleep. After all, Mentor, which employed him as a foster father, hadn’t told him that what he was doing could help cause her death.

Reports obtained by BuzzFeed News show that the baby was dressed in layers. She was in a “onesie,” over which was a set of fleece pajamas. Bloise swaddled her up, covered her with a crocheted blanket, and then, to prop her up on her side, he rolled up the edges of another blanket into cylinders, so they formed little walls around her, buttresses to prop her on her side. It was in complete contradiction to the standard of care.

By 10:45 a.m., as the snow continued falling outside, the girl’s foster mother had come home. She checked on the baby, and she found the little infant girl in her crib, blankets all around her, on her stomach, and she was not breathing. Her skin was “all sweaty.” The mother called 911. Her CPR certificate had expired — a violation of Mentor’s own policies, state investigators would later note — but she started infant CPR on the baby. Still, the infant was pronounced dead at 11:59 a.m., just about an hour later, at Beverly Hospital.

Brown, her real father, said he and the mother were called later that afternoon, at the homeless shelter where they lived. They had seen their daughter just the day before, and now they were told she was dead.

In Massachusetts, National Mentor is not just a major contractor, but an institution whose very DNA is intertwined with state government and social services. Edward Murphy, the current executive chairman of Mentor, was a former commissioner of the Massachusetts Division of Youth Services. Bruce Nardella, Mentor’s current CEO, was former deputy commissioner at that agency. The chair of the board of directors was a staffer in the Massachusetts Senate. Sarah Magazine, the spokesperson, worked in the Massachusetts governor’s office from 2000 to 2003. Dwight Robson, Mentor’s chief public strategy and marketing officer, was at the state treasury. One of Mentor’s vice presidents is married to state Sen. Thomas McGee, the head of the state Democratic Party.

“It is inaccurate to imply that there are a significant number of individuals working at The MENTOR Network who previously held high-ranking positions in Massachusetts state government,” Mentor said in statement. (Mentor markets itself as “The Mentor Network.”) “Of The Network’s corporate employees, less than 2% worked in leadership roles in Massachusetts state government.”

In a 2013 filing to the federal Securities and Exchange Commission, Mentor wrote that “we rely in part on establishing and maintaining relationships with officials of various government agencies, primarily at the state and local level but also including federal agencies.” But the company denies that it has any particular political clout in Massachusetts or that it exerted any political influence in the investigation into the baby’s death.

How could a little baby in such a company’s care die and yet remain anonymous? Back in late 2014, when BuzzFeed News began to investigate National Mentor, there were few publicly known facts about the girl’s death, certainly not her name. There were reports of the death of a 2-month-old and of an administrative finding of neglect in her death.

So, in November 2014, BuzzFeed News sent a request to DCF, asking for all records of the baby’s death.

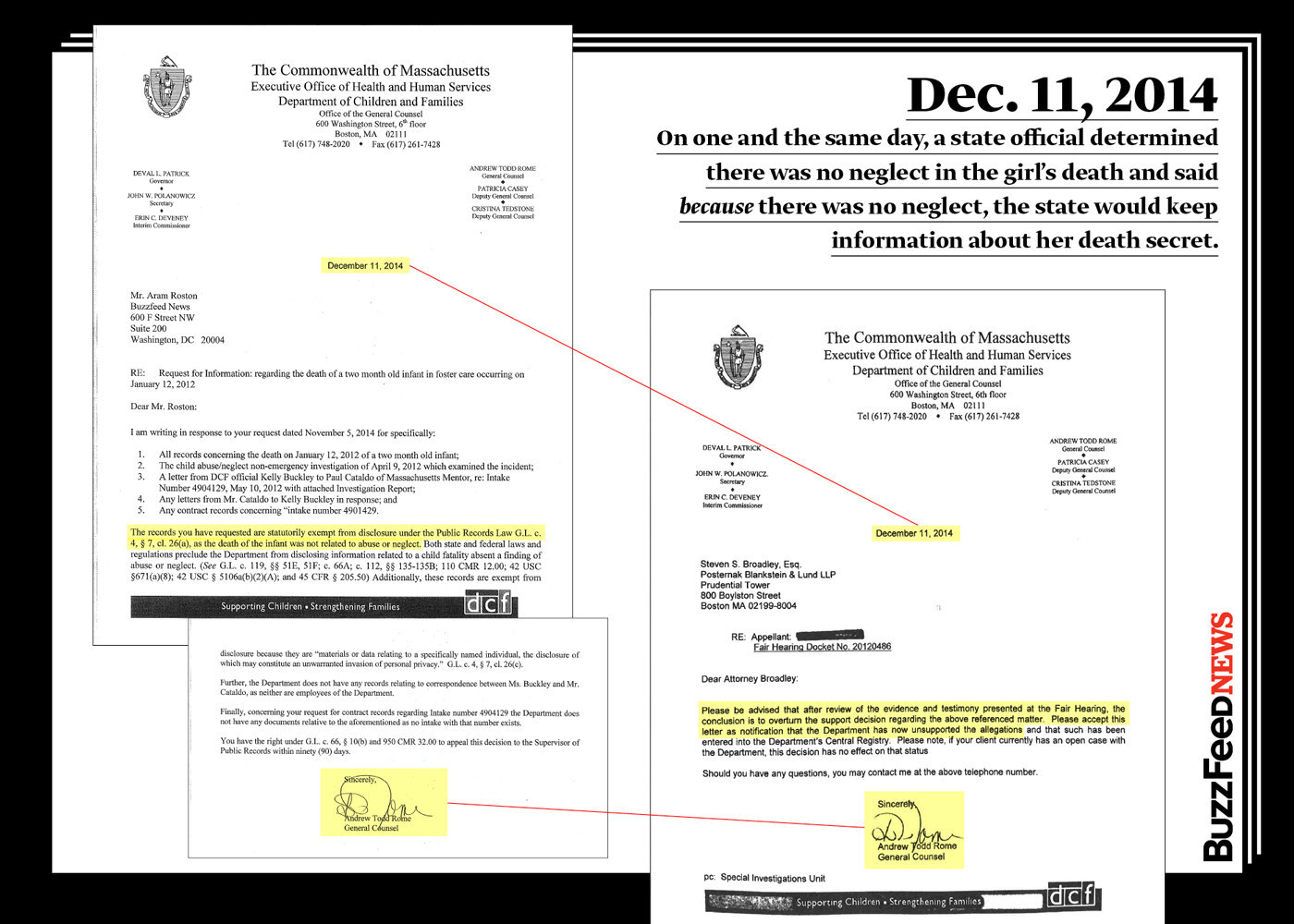

On Dec. 11, 2014, the top lawyer at DCF, Andrew Todd Rome, said he would provide no information to BuzzFeed News, because, he said, there had been no neglect in the child’s death. The records were “exempt from disclosure,” he wrote, “as the death of the infant was not related to abuse or neglect.”

It was illegal for him to tell us anything, he claimed. “Both state and federal laws and regulations,” he wrote, “preclude the Department from disclosing information regarding a child fatality absent a finding of abuse or neglect.”

That letter to BuzzFeed News was actually the culmination of an elaborate process, the final knot in a long and secretive bureaucratic trail by which the death of an anonymous, healthy baby, first ruled to be caused by neglect, was eventually transformed by the child welfare administration into nothing more than an unfortunate incident for which no one was to blame — and nothing need be disclosed. The life of the baby in the unmarked grave could be kept a secret.

Here is how that process worked.

In the aftermath of the infant girl’s death, in April 2012, DCF, which had contracted with Mentor and put the baby in the firm’s care, ruled that the baby’s death involved “neglect” by the foster father. “The allegation of neglect and death will be SUPPORTED,” the report stated.

But then Mentor hired a lawyer for the foster father to appeal the “neglect” finding. The company said it paid for the lawyer because the “extenuating circumstances” of the case “warranted our support.” The hearing was not open to the public. The lawyer, Steven Broadley, recalled in an interview that he argued that Mentor’s foster father took care of the child “in compliance with the training he had.”

A DCF worker, Maura Bradford, heard the case and wrote up her recommendation in February 2013. She didn’t respond to requests for comment, but in the report she reasoned that there was no case for neglect: Even though the baby had died of SIDS and had been put to sleep in a way that put the infant at risk for SIDS, no “causal link” had been established between these two facts. Since the death was “unexplained” — as most SIDS deaths are — and was not demonstrably connected to the unsafe sleeping conditions in the crib, the allegation of neglect, she wrote, should be “reversed.”

Robert Fellmeth, professor at the University of San Diego School of Law, was astonished when told of the reasoning. “To say that an infant dying of SIDS is not neglect after being put in the wrong position is insulting,” he said. “This foster parent is an agent of the corporation; if he’s not neglectful, they are. When you have people in that situation who don’t understand how to deal with SIDS, that’s neglect. I’m sorry! There are things you have to know, the absence of which is negligence.”

Right or wrong, Bradford’s recommendation to reverse the neglect finding was effectively just that — a recommendation. It wouldn’t take effect and become a final decision until it was signed and approved by her boss, according to a top DCF lawyer. So the recommendation to overturn the neglect finding lingered there in the file, not acted upon, and the department continued to consider the baby’s death a case of neglect.

Indeed, about three months after Bradford made her recommendation, Angelo McClain, who had just stepped down as head of DCF, was under oath in a lawsuit. He testified that his staff had found neglect in the death of the baby girl.

“Have you ever disputed that finding?” the lawyer, Sara Bartosz, of Children’s Rights, asked him.

“No,” he replied.

It was BuzzFeed News’ request for information that triggered the formal reversal of the neglect finding — a reversal that the state then used to reject the request for information.

On Dec. 11, 2014, DCF general counsel Rome wrote a letter to Broadley, the lawyer Mentor had hired for the foster father. “The Department has now unsupported the allegations,” Rome wrote. Broadley said it was the first he had heard of the case in almost two years; before then, he had never been told the outcome of the appeal.

On the very same day, Dec. 11, 2014, Rome also wrote to BuzzFeed News, declining to release any information on the grounds that the baby’s death did not involve any neglect.

To put it plainly: On one and the same day, Rome officially determined that there was no neglect in the girl’s death and also told BuzzFeed News that because there was no neglect, the department could withhold virtually all information about her case.

Broadley laughed when he heard Rome wrote to him and BuzzFeed News on the same day. “I’m not an investigative reporter,” he said. “It could be a coincidence! It could be related. I’m not in a position to speculate about that.”

Rome declined to speak on the record for this story. BuzzFeed News has been seeking documents from him for seven months.

But two senior officials at the Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services, which oversees DCF, defended the way Rome handled the case. Speaking on condition of anonymity, they insisted that the timing was a coincidence, not a cover-up.

One of the officials offered this explanation: Rome, he said, “gets the public record request. He opens up the file. And there’s an unsigned recommendation, signed by the hearing officer, to reverse, to overturn, the finding of neglect. No one had closed the loop on that hearing officer’s decision. If you want to say, ‘That doesn’t sound acceptable that it would take that long to approve a recommendation,’ I won’t quibble with that. But there’s nothing nefarious about that!”

The other official said, “We acknowledge the timing is strange.”

In the end, BuzzFeed News obtained from other sources many of the documents DCF tried to keep secret. But the name of the little baby who had died remained unknown. She was anonymous.

Then, this March, the city clerk of Beverly, Massachusetts, found a death certificate of an infant who died on Jan. 21, 2012, aged 2 months and 5 days. There it was, under “decedent name”:

Lily Marie Brown.

Her birth father said he and the mother were given Lily Marie's body back by the state, after she died. “I said, ‘So why didn’t you give her back before, when she was alive?’”

He said the couple was briefed a few times about Lily Marie's death. It was SIDS, they were told. But even though their parental rights had never been terminated, they were told nothing about the investigation, Brown said, or the neglect finding, or the sleeping practices. “They didn't tell us exactly how she was sleeping. On her back, her stomach, or her side. Or if anything was in the crib. They didn’t know nothing like that.”

The mother also said she’d been told very little. When BuzzFeed News informed her that state investigators found that Mentor hadn’t trained the foster parents in safe sleeping practices, she said, “That’s ridiculous.” After that brief telephone conversation, she declined to comment further.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a top state official declined to say what the parents were told.

Bloise, the foster father who was initially found to have neglected the baby, now works in construction. He told BuzzFeed News that he and the others in his household were fond of Lily Marie. He said his actions back in 2012 had nothing to do with the baby’s death, and he is still skeptical of the widespread recommendations for safe sleeping practices. “The baby is sleeping that way, or sleeping this way,” he said. “For me, the baby needs to be comfortable. As long as she is sleeping comfortably, that’s it.”

Lily Marie was buried Feb. 1, 2012.

“I couldn’t afford a headstone,” her father said.

For months, BuzzFeed News and its lawyers have negotiated for documents and information related to Lilly Marie Brown’s death — and DCF kept changing its stance.

In April, the agency gave a new legal interpretation that was even more strict than what it had said in December: Even if there was a finding of abuse, the department could say nothing about Lily Marie’s death.

And then, late last week, after BuzzFeed News told state officials that this story was soon to be published, there was a 180-degree pivot. Suddenly, the general counsel of HHS, Jesse Caplan, emailed a copy of the death certificate, confirming the baby’s name. Caplan also emailed the recommendation from the foster father’s appeal.

In short, after seven months of claiming that it was legally barred from releasing this information, DCF made an abrupt U-turn. Why? It’s unclear. A top lawyer at HHS said there had been no new interpretation of the law.

One gray day this June, a cemetery worker at St. Mary’s walked the row of baby graves, and then opened up his handwritten book to double-check if the unmarked plot was indeed the right one. "Yes," he nodded, pointing with his finger at the name. “Right here. That's her. Lily Marie.” In the grass there, where she’s buried, someone left a small Bible. Because of time and weather, it’s disintegrating now, its cover missing, torn to a random page.

“The cause of death in this tragic case back in 2012 was SIDS,” DCF spokesperson Rhonda Mann wrote in a statement to BuzzFeed News. “The child did not die as a result of abuse or neglect.”

For its part, Mentor seemed to acknowledge that the lack of safe sleep conditions may indeed have contributed to the girl’s death. In a statement, a company spokesperson wrote, “It is important to note that the cause of death was ‘sudden unexplained death’ and that there may have been other pre-existing conditions — beyond the manner in which the baby was placed to sleep — that, sadly, contributed to this child’s passing.”

The state and Mentor say that after Lily Marie’s death the company began training its foster parents in safe sleep practices. Last year, National Mentor won a new five-year foster care contract in Massachusetts.

At the cemetery, it was lightly raining, but yellow buttercups sprouted in the grass. Petals from the flowers of a black locust tree, 30 yards away, had been carried by the wind, and they sprinkled Lily Marie’s grave.

_____________________________________________________________

Talal Ansari contributed to this story.