EL PASO, Texas — Levi Lane shuffled into the pews of the El Paso County jail court still reeking of poultry fat from his night shift at a local pet food factory. Driving home at 2 in the morning, he had been pulled over for going 43 miles an hour when the limit was 35 and arrested on the spot for outstanding traffic tickets.

There in court, Judge Cheryl Davis, a part-time judge and bankruptcy lawyer, called Lane’s name. Barely looking up at him, Lane recalled, she read off his driving offenses, which included expired registration, no insurance, and not stopping at a stop sign — five traffic stops, totaling more than $3,400 in penalties.

If Lane paid up, he would have been released immediately. But there was no way Lane could afford that sum. The pet food factory paid $8 an hour, more than any other job he had had, but even so he made only $5,650 that year. Judge Davis did not ask about his financial situation, Lane said. Less than two minutes after the hearing began, it ended. In lieu of payment, Lane, who had no legal representation, was ordered to spend 21 days in jail.

What happened to Lane is illegal. It violates Texas law and two unanimous Supreme Court decisions, all of which bar courts from jailing people simply because they are too poor to pay their fines. One of the Supreme Court decisions even stemmed from a traffic case in Texas.

But in many courts across the Lone Star State, it is as if the law and the Supreme Court rulings never happened. A BuzzFeed News investigation into Texas judicial practice found that with no public defenders present, traffic court judges routinely flout the law, locking up people for days, weeks, and sometimes even months because they did not pay fines they could not afford. The result is a modern-day version of debtors prison, an institution that was common two centuries ago but has been outlawed since the early ’70s.

Unpaid fines are a vexing problem for municipalities across the country, and uninsured drivers can indeed be a hazard, but Texas law leaves no doubt as to how courts must handle someone who has been arrested for unpaid fines. And it provides an unambiguous, step-by-step process that includes an alternative punishment for those too poor to pay their fines.

First, before ordering a defendant to jail, a judge must hold a hearing to assess their finances. If the defendant is too poor to pay, the judge must offer community service instead. An indigent person can only be jailed if they have “failed to make a good faith effort” to do the community service. The result of the hearing must be put in writing.

All this is clearly laid out in Texas statutes — as well as in an official instruction manual for judges — and many of the state’s more than 2,100 judges who handle traffic violations and other petty offenses do follow the law.

But many don’t. In El Paso, where 1 in 5 people live below the poverty line, judges at the municipal court regularly send people to jail without holding a poverty hearing or offering community service. BuzzFeed News reviewed 100 of the court’s case files for people jailed for at least five days last year. Not a single one indicated that the judge had considered — or even inquired about — the defendant's ability to pay before locking them up.

Texas does not collect data on the total number of people jailed because they are too poor to pay traffic fines. But a BuzzFeed News review of case files in 20 Texas courts found that in nine there was no documentation of any poverty hearings. (Some jurisdictions offer payment plans, but even the down payments can be far larger than many poor people can afford.) When courts do assess poverty, they sometimes say even homeless people do not qualify as poor.

In defense of locking people up without assessing their ability to pay — or without offering community service — many judges demonstrate outright ignorance of the law. “There's no requirement for us to ask” defendants if they have the money to pay, said Judge Davis, who sentenced Lane. “Unless they bring up the fact that they have no money to pay, or that they would rather go on to a payment plan, or they want to do community service, then it's not offered,” she said. Cindy Ruthart, a judge in Lamar County in eastern Texas, echoed her, saying, “I’m not required by law to ask anything” about indigency. In rural Hereford, near the New Mexico border, Jennifer Eggen said that in her nine years as judge, she has never given anyone an alternative to incarceration other than paying up. When told that the law requires her to do so, she disagreed and said, “That's up to them to request that.”

El Paso city court Presiding Judge Daniel Robledo also said that judges were under no obligation to ask people about their finances — the onus was on defendants to raise the issue. He said that if someone acts responsibly and shows up to court, he’s more understanding, conducting indigency hearings and offering payment plans. In rare circumstances, judges offer community service. But once a person misses a court date, Robledo said, he and the 18 judges he oversees aren’t required to provide any alternatives.

When informed that Texas law says the opposite — that judges consider and document indigency for every defendant facing jail for unpaid fines — Robledo replied, “That’s a good point. That’s a good point. That’s a very good point.”

"I just find this to be outrageous," Susan Crump, professor at South Texas College of Law, said when told the findings of this investigation. She said that judges who jail people because they are too poor to pay are either “not knowing, or not able to read the law, or not caring.” Whatever the case, she said, such judges are “doing something that is clearly contra to what the law requires them to do."

Illegality aside, it is unclear what purpose is served by jailing poor people who can’t pay fines for minor offenses.

Traffic courts — known in Texas as justice of the peace or municipal courts — are big moneymakers for state and local government, raking in more than $1 billion from tickets in 2014. Jail time that indigent offenders serve, however, is given in lieu of payment, so incarcerating them does not make money for the government. Instead, it costs taxpayers money. El Paso spends about $375,000 a year to jail people for unpaid fines.

For people living in poverty, the consequences of such punishment can ricochet through their lives, costing them their jobs, devastating their ability to pay other debts, jeopardizing their ability to care for their children, and leaving them more dependent on the social safety net. By the time Lane got out of jail, his job at the pet food factory was gone. Soon thereafter, he said, he was back on food stamps. “It took time and opportunity out of my life,” Lane said. “I’m really, really hoping to God that I can find something to support me.”

Those who do manage to hold on to their jobs can still lose out on paychecks, which can have dire effects for people living close to the edge and can add chaos to difficult family situations. When Brisa Garcia was jailed for traffic fines she could not pay, she said she had to frantically search for someone to look after her 11-year-old son with disabilities.

Time spent inside jail can be traumatic, dangerous, or even deadly. Last week, the FBI announced it was investigating the drug withdrawal death of a Michigan man ordered to spend 30 days in jail for $772 in unpaid traffic fines. “The harms can be catastrophic to the defendant,” said Jennifer Laurin, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law.

It’s possible that jailing people could send a message to others to pay their fines, but in interviews with judges and other officials from 18 traffic courts across Texas, that rationale never came up.

Some judges told BuzzFeed News that they just don't have the time to conduct indigency hearings for every single person. They also said that many poor people actually want to sit out their debts in jail, rather than doing community service. Robert Doty, presiding judge in Lubbock's municipal court, said many defendants are "fine and dandy" with going to jail. "They get three meals a day," he said, "and a bed to sleep in."

In El Paso, Judge Davis said she feels she has to do something about poor people’s fines. "I can't just let them go because they don't have money," she said, adding that doing so would be "unfair to the rich person."

For people with money, traffic fines are an experience of an entirely different variety. That's not just because people with money can afford to pay their fines. Even if someone with money doesn't pay their fines — even if they rack up hundreds or even thousands of fines, deliberately, and then simply refuse to pay — they may still avoid spending so much as a single day in jail.

Charles Ackridge, the owner of a successful flooring business near Austin, drove through roadway tolls without an electronic pass. He did it about 6,000 times, accruing more than $80,000 in fines. He said he did it on purpose, as a personal protest against the tollways that sprouted up near his home.

Ackridge hired a lawyer and cut a plea deal with prosecutors in which he agreed to pay off just a quarter of what he owed — not all at once, but on a monthly basis. As long as he makes those payments, he will face no further prosecution. No warrants were ever issued for his arrest. As for jail time, Ackridge said, it was never mentioned.

"We’re not a society that jails people for traffic tickets,” said Rebecca Bernhardt, executive director of the Texas Fair Defense Project, a legal advocacy group. “We’re a society that jails poor people for traffic tickets.”

In a city with sparse and unreliable public transportation, Levi Lane figured that a car would open up possibilities. So a month before graduating from high school, he plunked down $2,500, half his and half a gift from a family member, for a black Kia Rio, adding zebra-print seat covers to make it his own. Soon, he got job at Whataburger and started classes at a local community college.

But it turned out that the Rio was a “total melon,” Lane said. As he racked up bills just to keep it on the road, he put off renewing his registration and car insurance. “I was making minimum wage and only getting 30 hours or less of work,” he said. “I had to choose between ‘Am I going to eat today’ and school payments this month and all the car stuff.”

In May 2012, an officer at a roadblock cited him for driving with no insurance, an expired license plate, and no valid inspection sticker. Between the fines and the court costs, the ticket was going to cost him about $775.

Three weeks later, he rolled through a stop sign and saw police lights in his rearview mirror. His insurance, license plate, and inspection were still out of date. This time the bill was more than $1,000.

Lane said he couldn’t pay — not with the money he was making at Whataburger — and he doubted that a judge would show him any mercy. So rather than miss his work shifts, he made what he now acknowledges was a mistake: He skipped his court dates.

Soon enough, Lane received letters in the mail informing him that warrants were out for his arrest. And they warned him that he would not be able to renew his registration until the warrants were resolved.

It’s at this point that people start to feel trapped, said Enrique Carrillo, a public information officer for the El Paso Police Department. They don't have enough money to pay their fines, and if they drive to work to try to make some extra money, they risk incurring yet more fines. "Even if you wanted to renew your license, if you have a warrant you can't,” he said. “It's a lose-lose.”

There is no doubt that Lane broke the law — repeatedly. Still, Lane and other El Pasoans caught in similar binds said they had little choice but to keep driving. A simple 20-minute drive to the other side of town can easily take three times longer on the bus — if you’re lucky and catch your connections. To keep his job, Lane said, he felt he had to risk more citations, though he also concedes he used the car to run errands and visit friends.

In December 2012, he was pulled over for a busted front headlight. The officer could have arrested him, but instead he handed him another $750 in fines for lacking insurance and registration. A few months after that, he said, he was driving his brother downtown to donate blood when he took a wrong turn down a one-way street. With the insurance and the registration issue again, it was $800 more.

In early 2014, Lane landed the job at the pet food factory. It was physically exhausting, but it was also a step up, to 40 hours every week and $8 an hour. With a little more time, he said, he hoped to start paying off both his school loans and his court debts.

There was a catch: He needed his car. Lane’s shift at the factory ended at 2 a.m., and the buses in El Paso shut down before midnight. So Lane drove, putting down a paper mat on the floor of his car to protect it from the bits of poultry fat that stuck to him when he left work.

About three months after he started his new gig, Lane pulled into his parking spot at a run-down apartment complex. Work had drained him, and he was “ready to face-plant on my bed.” But before he could open the driver door, a police car pulled up behind him.

In its earliest days, Texas was known as a haven for Americans fleeing their debts. People who left town seeking a fresh start sometimes chalked “GTT” on the doors of their newly abandoned homes, short for “Gone to Texas,” said Randolph B. Campbell, a history professor at the University of North Texas. When Texas was admitted to the union in 1845, its elders etched into the new state’s constitution: “No person shall ever be imprisoned for debt.”

That ideal clashed with reality, especially a 19th-century law that became known as “pay or jail”: If a defendant didn’t pay a court what they owed, they would have to either perform indentured labor or sit in lockup. The law didn’t mention race, but after the Civil War many Southern states, including Texas, allowed white people to rent out the labor of indebted black people, effectively re-enslaving them, according to Douglas Blackmon’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book Slavery by Another Name.

The law stayed in place through the automobile revolution, when Texas, like many other states, decided to adjudicate fines in low-level courts. Well into the second half of the 20th century, judges in these courts routinely put people in labor farms or behind bars if they couldn’t pony up, at the “pay or jail” rate of one day for each $5 in fines.

Then, in the late 1960s, a Houston man named Preston Tate picked up $425 in fines for nine traffic convictions, including running a stop sign, running a red light, and driving without a license. Tate made about $290 a month, which he used to support his wife and two children. Because he could not pay, the court ordered him to serve 85 days at the city’s prison farm. He took his case all the way to the Supreme Court.

Norman Dorsen, the lawyer who argued the case, told the court that Tate’s incarceration violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law, because a wealthy man in the same situation would have easily avoided lockup. “The law should be applied equally to the rich and the poor,” he argued.

The court agreed, unanimously, declaring that “the Constitution prohibits the State from imposing a fine as a sentence and then automatically converting it into a jail term solely because the defendant is indigent.” It said the state had to offer some kind of alternative to jail.

In response, the Texas legislature added a provision allowing judges to offer payment plans. Two decades later, in 1993, lawmakers added community service as another alternative for the poor. In 1999, they tweaked the law again to make clear that judges had to assess defendants’ finances before locking them up. A later revision to the law clarified that judges must put that assessment in writing.

About 15 years ago, El Paso criminal defense lawyer Fernando Chacon heard that clients were getting jailed for traffic tickets. He started filing emergency petitions to get them released. Juana Hidrogo, for example, said she was arrested and brought to jail while her 4-year-old was in the hospital with cancer. Her family was drowning in medical bills, she said, and couldn’t pay the tickets. He sued and won some settlements, but the city did not admit wrongdoing.

“I thought they had put a stop to all this,” he said.

These low-level courts, which Jennifer Laurin, the University of Texas law professor, calls “the darkest corners of the criminal justice system,” can be a world unto themselves. They handle only class C misdemeanors, such as common traffic violations and other petty offenses, for which the most serious official sentence is a fine. Because the offenses, and the official penalties, are so small-fry, judges are not required to provide lawyers to those who can’t afford them. And poor defendants rarely hire legal counsel of their own. (Lane did hire an attorney for one of his first traffic tickets and has very recently done so again.)

With no lawyers present, traffic judges rarely face checks and balances on their power.

“It’s kind of like a slaughterhouse,” said Andrew Sullo, a Houston lawyer whose firm, Sullo & Sullo, handles traffic cases. “If you’re walking to court alone, they see that.”

In El Paso alone, fines for traffic and other low-level offenses brought in more than $11 million in each of the past three years — nearly 4% of the city’s general fund revenue. Last year, courts in this city of 680,000 issued 87,000 arrest warrants for people who failed to show up in court for these cases, fell behind on fine payment plans, or didn’t complete community service.

When arrested on warrants, people in El Paso are often taken to the main jail, a building that has a court right inside. “You don’t have money,” Marlene Gonzalez, one of El Paso’s municipal judges, recently told a crowd of inmates at the jailhouse court. “That’s why you’re here.”

She and her colleagues churn through cases. In one 20-minute stretch, Gonzalez disposed of about two dozen people’s cases, a rate of one every minute.

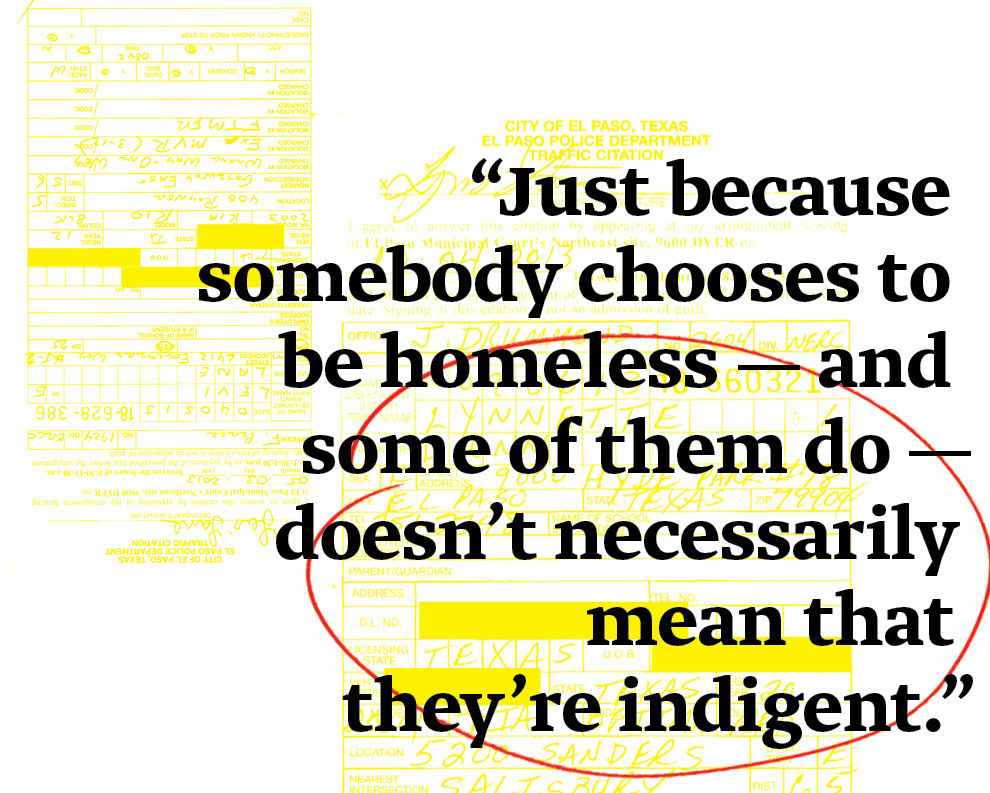

When courts do assess whether someone is indigent, how poor is poor enough to get offered community service instead of jail? The Lubbock Municipal Court found 32-year-old Shayne Moore "not to be indigent," even though in the county jail logs he is listed as homeless. (Moore couldn’t be reached for comment.) He was jailed for 10 days in 2013 on more than $1,500 in unpaid traffic-related fines.

Texas law does not define how poor a defendant must be to qualify for alternatives to jail, so individual judges make the determination. They often register their decisions by simply ticking off a box on a court document, no explanation added. In Lubbock, BuzzFeed News reviewed case files of seven other homeless defendants — charged with petty, fine-only offenses such as public intoxication or making too much noise — whom the court deemed “not to be indigent.”

“Just because somebody chooses to be homeless — and some of them do — doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re indigent,” said Doty, the presiding judge.

Going to jail can erase a person’s original traffic fines, but not the expensive surcharges that the state tacks onto some tickets. And until those charges are paid off, drivers can’t renew their licenses. As a result, a driver may serve jail time for the fine itself, then get out of jail, get pulled over again for driving without a license, and go through the cycle all over again. For some, the cycle can be almost impossible to escape.

Carina Canaan said she started driving to school before she was old enough to get a license. Now she wishes she hadn't, because the tickets she started racking up quickly topped $3,000. When she was old enough to go legit she was told she couldn't until she paid off the fines.

She spent 10 days locked up to pay them off while pregnant with her first child. But she still can’t get her license until she pays off the surcharges, which she says she can't afford. And she has been turned down for several jobs, including one at a call center, because, she said, she didn't have a valid license.

Levi Lane, the man arrested after a night shift at the pet food factory, said he definitely would have taken community service over jail if the judge had offered it. He was scared of the guys he was locked up with, but even more, he was scared of losing the financial toehold he had gained before he was incarcerated.

In the year and a half since he’s been out, he has earned what little money he can by making balloon animals. He gets hired for birthday parties or makes the rounds at chain restaurants in search of a few bucks or the “starving artists special,” a slice of the pizza that one of the tables is not planning to eat.

Jobs that seemed possible before now feel out of reach. Working for a cable company or fixing DVD vending machines would both pay above minimum wage. But those jobs require employees to use company vehicles, and Lane figures there’s no way they’d hire someone with outstanding tickets. He shares a small apartment with two of his brothers, the youngest sleeping on the couch in the living room. “I want to do more than just scrape by,” he said.

Even after serving time, he still owes the city $510 in court fees that he couldn’t pay off with time behind bars. On top of that, Lane said he now owes the state $2,600 in surcharges and has received letters from the state Department of Public Safety threatening to suspend his license if he doesn’t pay soon.

Recently, a friend told him he could petition the state to say that he couldn’t afford the surcharges. He called, and if he’s approved, he was told, the tab could drop to about $500.

It was the first time anyone told him there might be a way out of all this.