When Tara Thompson, a 44-year-old mother of two, began working at a Dollar General in Holly Hill, South Carolina, in December 2021, she made $11.75 an hour, a bump up from the $9.50 she previously made at McDonald’s. Her paychecks amounted to around $1,500 a month if she clocked in at least 32 hours each week which she expected. Combined with the income from her partner, who made a slightly higher wage from his job at a payment processing company, Thompson calculated that the pair earned just enough to cover their $3,000 in monthly expenses.

“Eleven an hour is not enough money for anyone to live off, but we had to find a way to make it work,” she said. The 1st of the month brings a $1,100 mortgage payment on the house she shares with her partner. Her $800 car payment comes due on the 5th. Light and gas are a combined $275, due by the end of the month. Gas for her daily commute to work accumulates to around $400. School supplies and clothes for her growing kids add to the monthly expenses, as does insurance. “At the end of the day,” she said, “I have to have my lights, I have to be able to feed my kids, I have to have gas to get back and forth to work.”

“Eleven an hour is not enough money for anyone to live off.”

But her new job didn’t offer consistent hours. In fact, the managers in charge of scheduling shifts never assigned Thompson more than 22 hours a week, and sometimes it was as few as 15, leaving her with weekly paychecks hovering between $150 and $250. Her 45-year-old sister Taiwanna Milligan, who also worked at the store, said she was rarely assigned more than 16 hours a week, and was only able to work more than 20 if a coworker had to miss a shift. Keisha Brown, a 38-year-old mother of two who made $15 an hour as the store’s assistant manager and expected to work 40 hours a week, said she usually clocked around 30. “I’m one of the hardest-working people, but you wouldn’t know based on my paycheck,” Brown said. “They don’t want to pay you the hours.”

Dollar General did not respond to questions for this story, but in a statement said, “We strive to create a work environment built on trust, mutual respect and opportunity for all employees to grow their careers, serve their local communities and feel valued and heard.”

Some months, Thompson said, she has been unable to make ends meet.

“I just have to choose what’s going to get paid and what’s not going to get paid,” Thompson said. “ [If]I pay the light bill this month and truck this month, then they just won’t get paid next month when I pay the mortgage.”

Service workers making low hourly wages at jobs across the country are facing similar dilemmas and struggling to earn a living. As costs for housing, gas, and food rise, their pay stays stagnant. Despite the increased national attention showered upon the service workers who kept the economy running while facing the risk of infection in the early months of the pandemic, the “hero pay” raises that companies installed in 2020 are now gone. The government stimulus payments, eviction moratoriums, and increased unemployment assistance that helped families who were making lower incomes to cover basic needs are also gone. Since then, political concerns over income inequality have taken a backseat to debates over abortion rights, extremist violence, crime rates, and Republican efforts to ban books and curriculum drawing attention to America’s sins.

Minimum wage in the US, at $7.25, hasn’t risen since 2009. South Carolina, where the minimum wage remains at the national standard, is one of 26 states that prohibit local governments from setting a higher rate. With broad authority to determine wages, hours, and benefits, employers have little incentive to cut into profits by increasing pay enough to keep up with the rising cost of living, and workers often can’t find higher-paying jobs elsewhere.

As the midterm elections approach, Thompson and Milligan say they see no reason to think that lawmakers have any interest or ability to help them through the problem that affects them most directly every day. Just two states have ballot measures proposing a minimum wage increase: Nebraska’s would steadily increase the state rate from $9 an hour to $15 over the next four years, and Nevada’s would bump its $9.50 standard up to $12 by July 2024. A ballot initiative in Washington, DC, would require restaurants to pay their servers the city’s $16.10 minimum wage regardless of how much they earn in tips. But workers in states that have been resistant to wage increases, such as South Carolina, can only wait for federal standards to increase their own. Though President Joe Biden initially proposed a $15 federal minimum wage in his 2021 economic stimulus package, the provision was scrapped from the final bill because of Republican opposition. For a wide swath of workers with low incomes, their financial struggles continue on with no help in sight.

“Wages need to be raised,” Thompson said. “But I haven’t seen any politicians doing anything about that.”

“Because they’re wealthy,” Milligan added. “They got it. So it doesn’t even matter to them.”

That absence of government support has left service workers to figure out solutions for themselves. With no faith in institutions, Thompson and Milligan are seeking assistance within their own communities. Relatives have moved in together, neighbors have carpooled, mutual aid programs have sprouted, loved ones have loaned money, and interpersonal support systems have stretched thin to cover the yawning gaps in America’s social safety net.

In mid-July, after Thompson missed work to accompany her son to the hospital for an emergency surgery, her manager fired her.

“Wages need to be raised,” Thompson said. “But I haven’t seen any politicians doing anything about that.”

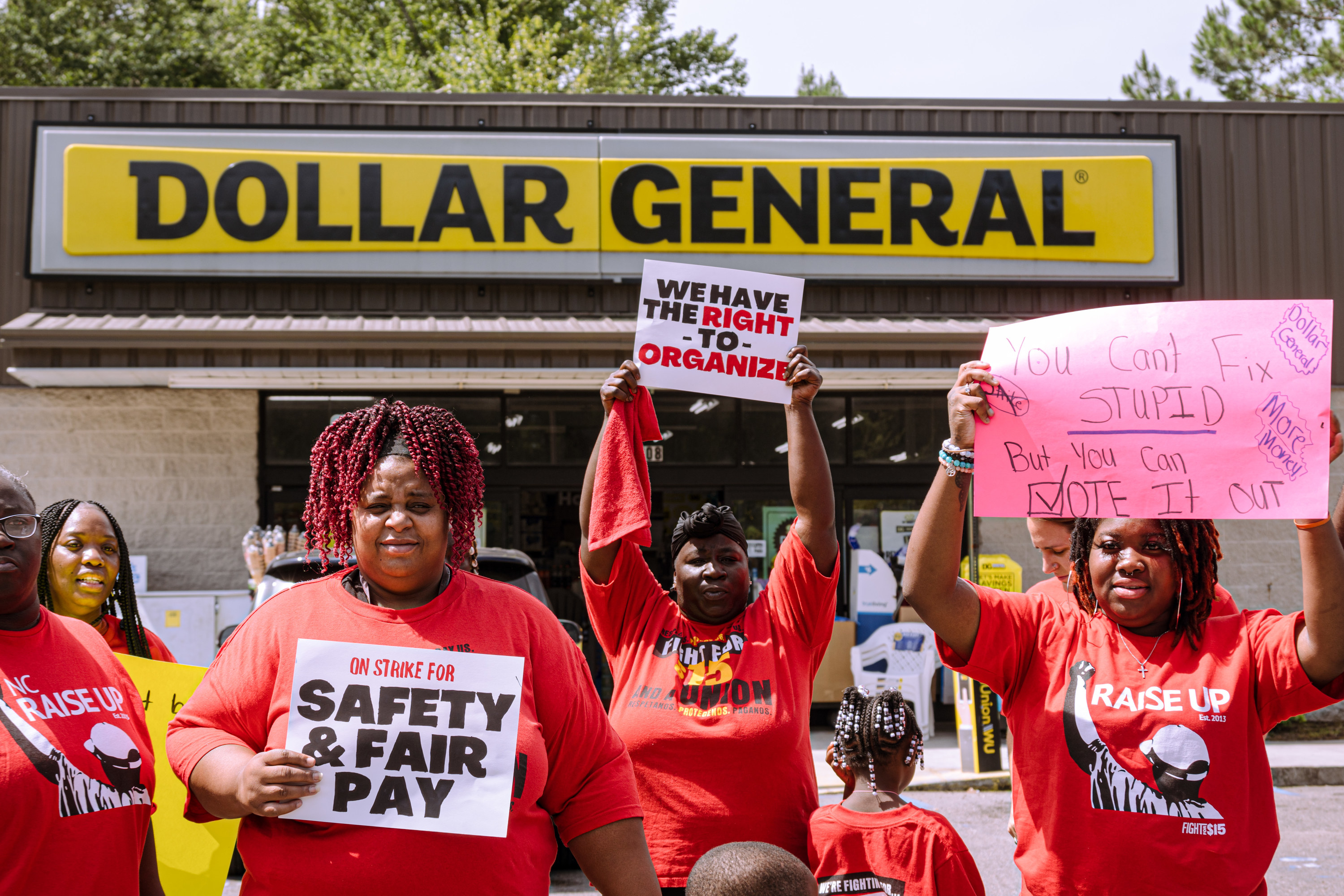

Her colleagues stood up for her. Later that week, Milligan, Brown, and other Dollar General workers went on strike, part of a wave of protests across service industries that pay low wages in recent years. Gathering with poster board signs outside the store, they called on management to give Thompson her job back, assign more employees to each shift to give them more hours and lighten their individual workloads, and make their store safer by adding more security cameras and fixing a broken lock on the front entrance. But Thompson wasn’t rehired, and almost nothing changed.

“All they did was clean up the store,” Milligan said. “They weren’t giving us enough to live comfortably while taking care of our family and not have to live from check to check.”

Then two months later, on Sept. 19, Dollar General announced that it was closing the Holly Hill branch. The company declined to answer questions about its reasoning for shutting down the location. “With thousands of stores serving communities around the country, the decision to close any particular store may be due to a wide range of possible factors,” Dollar General said in a statement to BuzzFeed News.

Suddenly unemployed, its remaining workers scrambled to figure out a way forward, just as Thompson was.

“My plan,” she said, “is just trying to catch back up from not being able to work.”

Not long ago, in 2017, Thompson felt financially stable. Though her McDonald’s job paid just $9.50 an hour, she clocked in 40 hours every week, enough to cover her apartment’s $350 rent. But that bill rose quickly over the next few years, reaching $950 by the start of 2022. Once the emergency pandemic government programs expired, she knew she had to make changes to stay afloat.

Talking with her mother and her sister Milligan, she realized that they were all struggling with the same bills. The women decided they would be better off pooling their resources.

In August 2021, with interest rates reaching new lows, Thompson and her partner bought a prefabricated home. The following month, her mother and Milligan moved in with them. Four adults and five children crammed into the four bedrooms, sharing groceries, vehicles, and bill payments.

“Splitting the costs was going to be better for everyone,” Thompson said. “We each take different pieces, but it comes out pretty even in the end.”

“I have to make sacrifices,” Milligan said, “and sometimes with food, we'll just have to eat noodles.”

Her mother watches the kids while the other adults are at work, which Thompson estimates saves them hundreds of dollars a month.

“Daycare is so high, and when you’re making $10, $11 an hour and you got bills, it’s just no way to pay $130 per child when you got more than one kid,” she said.

After they moved in together, Thompson applied for the Dollar General job, thinking that the higher hourly rate would mean a higher paycheck. Milligan applied a few months later.

The job’s low hours and inconsistent scheduling generated constant uncertainty over the household’s budget. Milligan said she has relied on loans from friends and extensions from bill collectors.

“I have to make sacrifices,” Milligan said, “and sometimes with food, we'll just have to eat noodles.”

Thompson tried to supplement her income by starting a catering business, cooking at home for people who heard about her service through word of mouth. “In a good month, I might get one or two orders, but then I can go for six months with no catering business, so it's not money I can count on,” she said. “We are barely getting by.”

When they entered the workforce as adults in the late 1990s, Thompson and Milligan had reason to believe their country’s economic system offered them a path to upward mobility. The US was the richest country in the world, growing ever more powerful as it oversaw an expansion of capitalist hegemony across the globe. Minimum wage rose four times from 1990 to 1997. Homeownership seemed within reach to almost anyone with a full-time job.

Then a financial crisis cratered the economy. Occupy Wall Street protesters called for more equitable wealth distribution amid the Great Recession, Bernie Sanders ran for president on a platform to expand social services through a wealth tax in 2016, and labor organizing efforts during the pandemic birthed the first unions at Amazon and Starbucks. Across the country, a movement for higher wages led by the Fight for $15 coalition has organized strikes, filed workplace complaints to labor agencies, and lobbied for bills such as California’s AB 257, which implemented stricter oversight of working conditions in the fast-food industry. Milligan and Thompson contacted Fight for $15, which advised them on employee rights and protest tactics in the run-up to their strike at Dollar General.

“In order to get what you want and get what you need to feel comfortable, you gotta stand up and fight for it,” Milligan said. “We’re not just gonna take it.”

Yet for all the impact those movements have had, Thompson and Milligan haven’t seen any improvement in their day-to-day circumstances. Minimum wage is less than $2 higher than it was in 1997, when median rent in the US was around $600, less than half of what it is today.

Even the most prominent recent effort to help people stabilize their finances, Biden’s program to cancel as much as $20,000 in student loans for qualifying recipients, has stalled, held up in the Supreme Court.

One student borrower, 38-year-old Terrika Coakley-McCoy, racked up $72,000 in loans at the University of Phoenix and the University of Cincinnati in hopes that a college degree would ensure her more than the $14.50 she was making per hour as a pharmacy assistant. But it didn’t make much of a difference. Her expenses continued to outpace her income, and today she makes $18 an hour as a medical assistant at a hospital in Ohio.

Coakley-McCoy’s husband makes $31 an hour as a bus driver, and together the couple earn just enough to cover basic needs, unable to save or create an emergency fund. They rely on credit cards to cover any gaps in their budget.

The couple cycles bill payments strategically, she said. With their first biweekly paychecks each month, which amount to around $2,000 combined, they pay off their $1,300 rent and outstanding credit card dues. Their second paycheck goes toward the $215 car insurance, $90 daycare for their young daughter, around $320 in utilities, and their two car notes, which add up to around $800. For her 30-minute commute to work, she said, she spends as much as $250 each week on gas.

Her student loan payments, which she deferred, resume next year. “I shudder to think how I’m going to pay those,” she said.

Coakley-McCoy said that she and her husband had once envisioned having four kids together, but “we can barely afford one,” she said. “It’s harder than I thought it would be. It’s a scary time.”

Living in Cincinnati, Ohio, a swing state with a disproportionate impact on presidential elections, she stays attuned to politics and regularly reads the news. Like Thompson and Milligan, she has grown disillusioned.

“Nobody is really talking about things that are impacting me,” she said of the candidates running for office in her state. “So nobody really has my vote at this point.”

Over time, she said, she came to realize that she couldn’t count on finding satisfaction in her paycheck or any sense of optimism for an improvement in financial circumstances, even as she aspired to earn enough income for vacations and her daughter’s college tuition. Instead, she said, she has learned to find peace within her own household.

“We find joy in each other, my husband and I,” she said. They spend their free time at home, often with her best friend, forming a trio they call “the life partner gang.” “We basically check in with each other every single day to decompress and de-stress about our day.”

In the six years since he started delivering food for Uber Eats, Grubhub, and DoorDash, Ranjit Geuli hasn’t seen any increase in his income, but the rent on his Queens apartment has risen from $1,400 to $2,000. To pay the bills, he has spent more hours on the job — sometimes 80 in a week — making 25 deliveries a day, working through holidays and inclement weather because they bring higher demand. On his best days, he said, he comes home with $100.

“We work hard but we’re not getting paid enough,” said Geuli, who is 30 and previously worked as a managing director for an employment recruitment center in Nepal before immigrating to the US. “We have to sacrifice our happiness.”

Seeking an outlet for his frustrations, he found solidarity among fellow delivery workers he met through Facebook and WhatsApp groups, where he found a “platform to share [their] feelings,” he said. “The company doesn’t have a union, so we have no way to complain or explain what’s happening to us.”

Only then did he realize that his problems weren’t unique but standard. Other drivers explained how they juggled working for multiple apps at once in order to maximize the number of deliveries. Some left tips on where to find the cheapest gas prices and most accessible public restrooms in the city. Geuli learned about efforts to protest against their working conditions and attended rallies organized by the Justice for App Workers coalition. Seeing that so many people were likewise struggling to make ends meet, Geuli concluded that in America “everything is challenging.”

Naomi Ogutu, a mother of three who started driving for rideshare companies in 2016 after emigrating from Kenya, considered herself “very lucky” to have a job with flexible hours that allowed her to shuttle her kids to and from school. She leased a Chevy Suburban because the seven-seat SUV allowed her to earn higher fares as an UberXL driver that would make up for the vehicle’s higher gas cost and $660 monthly payment. Working 60 hours a week, she could earn close to $8,000 in a month before taxes.

But when ridership decreased during the pandemic and the government assistance programs ended, her monthly income dipped below $4,000. No longer able to afford rent on her Brooklyn apartment, which had risen to $2,500, she moved her family to Newark, New Jersey. Her rent was cheaper at $1,600 a month, but she had to spend $450 a week on gas and around $25 in tolls for daily trips to and from New York City, which had higher customer demand than in the area around her new home.

“The fares are not increasing, but our expenses are skyrocketing,” said Ogutu, who was a marketing professor in Kenya with a master’s in business administration. “The app companies connect us with the customer, but the main expenses of the business are paid by me.”

As gas prices began a steep rise in early 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine, Ogutu found that her commutes into the city weren’t always worth the fuel costs she had to pay. To keep her income steady, she has found opportunities through the people around her. Using connections she has built through social media groups and the Justice for App Workers coalition, she picks up jobs driving private clients.

When a limousine driver she knew got a flat tire while ferrying a group from Brooklyn to Atlantic City in October, Ogutu swung by to take them the rest of the way, then handled the driver’s other ride appointments that day. When she picks up people from the airport or knows acquaintances from Kenya are visiting New York City, she offers her services as a personal driver for their trip, earning nearly $700 for a full day’s work.

“I started doing this when things got really tough,” she said. “I realized this is better.”

Ogutu’s efforts to reduce her dependency on rideshare behemoths reflect a growing resistance to employment terms that more and more workers deem exploitative, as more people making low wages protest labor conditions and quit their jobs.

But few alternatives exist.

After the Dollar General closed, Milligan applied for a number of jobs, including one at Walmart, which offered about the same pay without any guarantees of full-time hours.

Seeking a way to pay the bills while searching for full-time employment with health insurance, Milligan found gigs doing housework for older relatives and neighbors, and resurrected an old side hustle she first developed when she was 12: She braided hair for her cousins, nieces, and nephews. Those relatives told their friends about the service, and soon she was doing three heads a week, at $150 each, totaling more than she made in a week at Dollar General.

“They’re just a walking billboard for me,” she said of her new clients. “‘Cause a lot of people love to get their hair braided and ask them, ‘Who did your hair?’”

Thompson didn’t have a side hustle to fall back on as she applied for jobs. Through August and September, her search yielded no offers. She continued rotating her bill payments, falling further behind each month. Her loved ones ensured the lights stayed on and the house was never at risk of foreclosure.

Then one day in October, a temp agency she signed up for offered her a position at a Mercedes-Benz factory. The job paid $14 an hour and guaranteed 40 hours a week.

“I was so happy,” she said four days after she was hired. “It’s like a burden lifted up from my shoulders.”

She hopes the factory hires her for a permanent position. ●