This is part of a BuzzFeed News Investigation. Other main stories in the series include:

Detective Guevara's Witnesses and related video

Roberto Almodovar Finally Walks Free

The Night Shift

It's Cold Outside

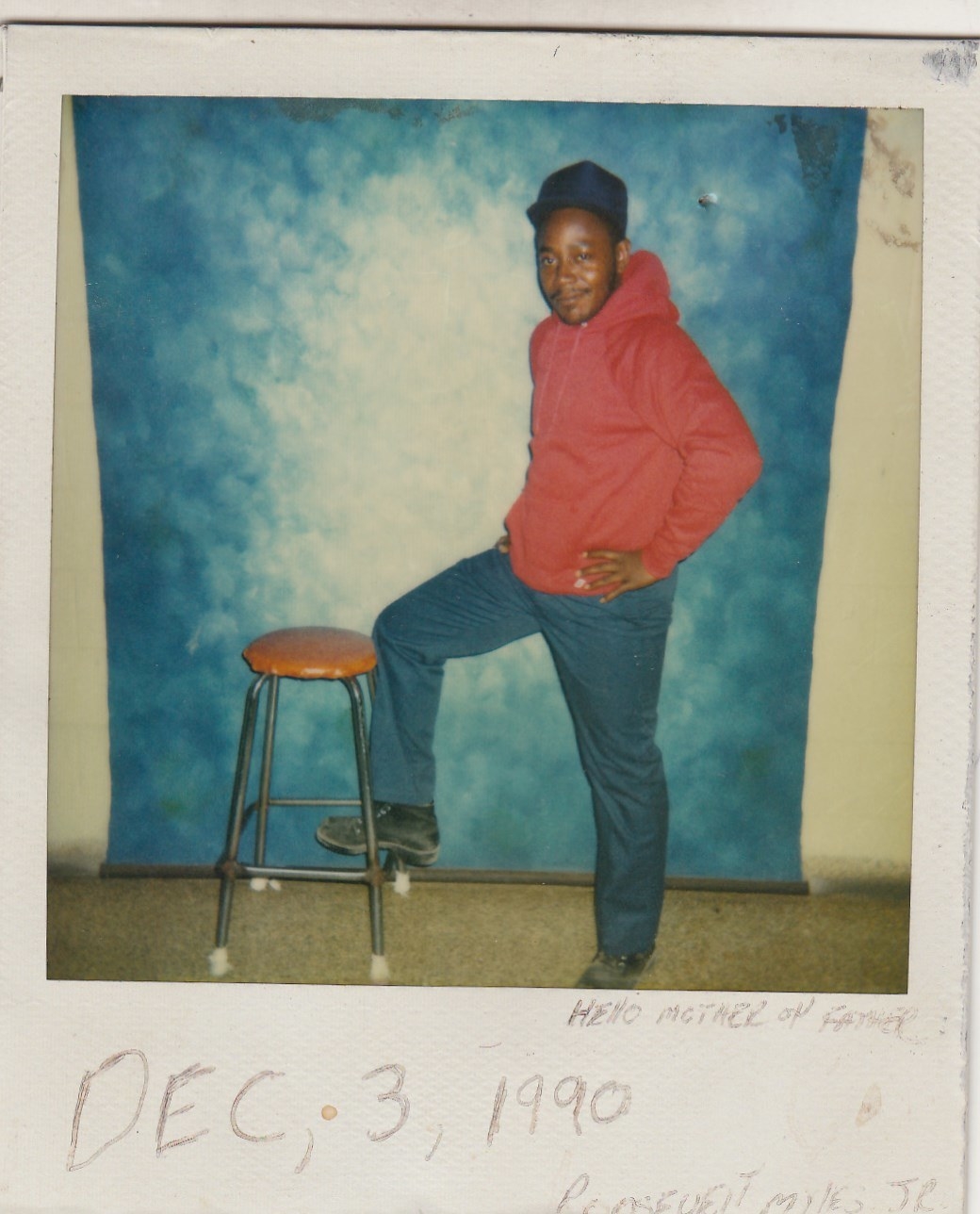

Roosevelt Myles was eight years into a 60-year murder sentence when he picked up the phone to call his father.

“Daddy,” Myles said from Menard Correctional Center in Illinois, “I get to prove my innocence.”

He read his father the Illinois Appellate Court decision that he’d just received — the one granting him a chance to argue that his public defender had provided “ineffective counsel” at his trial. That lawyer hadn’t even called the three witnesses who could have confirmed Myles’ alibi. Myles said he had been framed by corrupt police officers.

His father yelled out the news to his wife, who praised Jesus in the background.

That was 16 years and seven months ago. Yet Myles still hasn’t had his day in court. He remains in prison year after year, enduring a delay that legal experts have called unprecedented and unconscionable. And in the time that has passed, a key witness to his alibi died, making it much harder for Myles to prove his innocence should he ever get the chance.

The case of Roosevelt Myles is a striking example of how broken the justice system is in Chicago. At every level, the safeguards that are supposed to protect people crumbled: He was tried without adequate legal support and convicted without solid evidence, and has rotted in prison despite an order that he be allowed to seek justice in court.

Earlier this spring, a BuzzFeed News investigation revealed that at least 51 people have accused Chicago detective Reynaldo Guevara of framing them for murders they did not commit. City officials, county prosecutors, and federal authorities failed to adequately address mounting complaints of police misconduct over a span of decades.

He was tried without adequate legal support and convicted without solid evidence, and has rotted in prison despite an order that he be allowed to seek justice in court.

Myles alleges that officers from the same unit as Guevara framed him for murder. He says they pressured witnesses who initially said Myles was not the shooter to change their accounts, and that officers failed to investigate his alibi or to pursue other leads. He says one of those officers beat him with a phone book and flashlight as two other detectives looked on.

Any defendant can claim to have been framed. Myles’ lawyer didn't raise those allegations during the original trial, so they have never been ruled upon. The appeals court’s order, the one that Myles called home about with such excitement, would have given him the chance to air them in court, and would have allowed a judge to assess their credibility.

Instead, that court order has sat on the desk of Dennis Porter, the Cook County judge who presided over the original trial. The hearing has undergone more than 70 delays, most of them requested by Myles’ public defenders — the very people who were supposed to be advocating on his behalf. For a decade and a half, they haplessly passed the case from one lawyer to the next, taking months or even years to familiarize themselves with it. Meanwhile, Porter himself had the power to set and enforce deadlines, but he did not do so. At least four motions to move the case forward have been filed by various parties. Porter hasn’t ruled on any of them.

Samuel Hayman, an assistant state appellate defender who works with appeals every day but who is not involved in this case, calls the inaction on Myles’ hearing “insane.” He adds, “At the very least you’d expect the judge to insist that something happen over the last 15 years.”

A spokesperson for the Office of the Chief Judge responded on Porter’s behalf to questions about the case by pointing to an Illinois Supreme Court rule prohibiting judges from publicly discussing pending cases.

One public defender who worked on the case, Marienne Branch, said the post-conviction unit where she worked “did nothing for years,” and said her own representation of Myles, which came at a low point in her life, left her feeling embarrassed and regretful. “It’s disgusting,” she said.

Another public defender explained that his work on Myles’ case stalled because Cook County, which operates the public defender’s office, failed to pay the private phone company that handles collect calls from inmates. Public defenders were unable to take their clients’ calls, he said, making it difficult to work on their cases.

Lester Finkle, the current chief of staff for the Cook County Law Office of the Public Defender, says other prisoners have also languished for years waiting for hearings.

“It’s unusual but it’s not unique. I’m not saying that as a positive statement,” Finkle said. BuzzFeed News found another man, Thomas Sierra, who says he was framed by some of the same detectives who worked on Myles’ case. He has been waiting for 15 years on his post-conviction hearing.

“The whole system failed.”

In the sixteen and a half years that Roosevelt Myles’ case has stalled, time was just the beginning of what he lost.

Ronnie Bracey, a friend whose apartment Myles says he was visiting at the time of the murder, is no longer alive to testify in his defense. And Myles’ parents, who were so thrilled to receive the news that their son would get another chance at freedom, have died too.

“He’s being denied access to the courts,” said Jennifer Bonjean, a New York-based civil rights attorney who became interested after Myles wrote her about his plight. “The whole system failed.”

The case against Myles seemed straightforward.

In the early hours of Nov. 16, 1992, prosecutors told the jury, 16-year-old Shaharian “Tony” Brandon stopped by the home of his new girlfriend, Octavius Morris. After spending about a half hour talking, the young couple headed out about 2:45 a.m. to eat. Within steps of Morris's front door, a man approached them yelling “This is a stickup,” and then fired two bullets into Brandon’s torso.

The prosecution claimed that two witnesses, Morris and a sex worker named Sandra Burch, told police that Myles was the shooter. Burch, who witnessed the shooting from a car she was sitting in with a john, died before trial. That left Morris’s eyewitness statement as the only evidence in the case.

The police reports, however, contain many discrepancies.

First, there was what the police noted as “some conflict in the statements of the witnesses.”

Morris, the victim’s girlfriend, told the first officers on the scene that two males approached her and Brandon.

Burch, the sex worker, said it was one.

Morris claimed they came out from under her front porch.

Burch said the lone male emerged from the gangway next to Morris’s home, on the other side of the house from the porch.

Morris said the shooter jumped in a getaway car to flee the scene; Burch claimed he fled on foot.

Morris said one of the assailants wore all black, standing about 5 feet 6 inches tall. The other was about 6 feet tall and wearing a white jogging suit. Both men were in their late teens. Burch said the gunman wore a red jacket.

Myles stands 5 feet 6 and was 28 the night of the murder, almost a decade beyond his teens. He said he was wearing blue that night.

He contends that competent police officers — or, failing that, a competent defense attorney — could have proven he wasn’t there at all.

At the time, he was a drug addict who supported his habit by dealing. But he wasn’t, he said, violent. He said he heard the gunshots that killed Brandon, from several blocks away, as he was leaving his friend Bracey’s apartment.

Morris was clear: She said Myles didn’t do it.

After the shooting, he said, he walked by the crime scene — dressed in the color he wore so often that most everyone in the neighborhood called him Blue — on his way to a corner store to buy cigarettes. Police stopped him and walked him over to a police car where Morris was waiting. They asked her if Myles was the shooter.

It was just minutes after the murder, and Morris was clear: She said Myles didn’t do it. Police released him.

Hours later, a second wave of officers reinterviewed Burch and Morris at the hospital where Brandon lay dying. Both witnesses reiterated their statements. The officers who interviewed Burch concluded her statement by writing, “she could add nothing further.”

Yet the reports show that week by week, each time officers reinterviewed the witnesses, their stories inched closer together.

Burch went from saying there was nothing else she could add, to naming Myles as the shooter, despite telling officers she didn’t see the shooter’s face.

By Dec. 7, 1992, three weeks after the murder, Morris changed two critical facts in her account. She said that she only thought there were two shooters but didn’t see both, despite having given detailed descriptions of both assailants. She also told officers that she knew immediately that Myles was the shooter, but that she had claimed otherwise because she feared him.

He was arrested the next day. According to an affidavit he filed with the Independent Police Review Authority, while Myles was in the station house one of the detectives, Anthony Wojcik, hit him repeatedly with a flashlight and phone book, pressuring Myles to confess.

Wojcik has a complicated record on the force. One court filing cites 13 other cases in which Wojcik “has been under investigation for coercing defendants and/or witnesses.” One of those defendants, Eruby Abrego, claims that Wojcik punched him repeatedly, to the point where he vomited blood and falsely confessed to a 1999 murder. His post-conviction complaint is still working its way through the courts. Beyond those 13 defendants, all of whom were found guilty, there have been at least two additional cases in which defendants accused Wojcik of threats or violence. Both defendants were found guilty.

In 1988, four years before the shooting, FBI agents tailed Wojcik as part of a police corruption investigation. And at the time he arrested Myles, the officer was under investigation by the police department’s internal affairs division for falsifying a police report in an unrelated case. He later admitted falsifying the report, and was reprimanded. The FBI declined to comment.

Over the course of his career, Wojcik accumulated at least 41 citizen complaints; the typical officer receives no more than five. Only three were deemed to merit some form of discipline. A Department of Justice report released in January excoriated the civilian complaint system in Chicago, calling it “broken” for failing to take civilian complaints seriously.

On behalf of Wojcik, attorney Darren O’Brien denied any allegations of misconduct. “My client has never done anything improper while investigating any CPD matter,” O’Brien wrote in an email to BuzzFeed News.

Each time officers reinterviewed the witnesses, their stories inched closer together.

In 1994, two years after the shooting, Morris, the main witness, told investigators that police had pressured her into saying that Myles was the shooter. In a signed statement, she said, “I kept saying no until one night I just got tired and said he was Blue. But, all the time I was telling them it was a light-skinned man or boy, but they kept saying Blue’s name, so I said Blue did.”

By the time of the trial, another two years had passed, and Morris reverted back to identifying Myles as the killer. Morris did not respond to requests for comment sent to an email address and a physical address listed for her in public records.

Meanwhile the police appear to have ignored other leads. On the night of the crime, Morris told officers on scene that gang tensions ran high in her neighborhood. That would have made Brandon, listed in police reports as a member of the 4 Corner Hustlers, vulnerable to violence from members of rival gangs.

His uncle told police that earlier the same day Brandon had said he feared visiting his new girlfriend at her home because her ex-boyfriend had shot at him. Records provided by the Chicago Police Department don’t show that officers followed up in any way.

Despite all the contradictions in the case, the jury took about 90 minutes to return its verdict: guilty. Myles was sentenced to 60 years in prison.

His public defender at trial, Anthony Eben, recently told BuzzFeed News he had no recollection of the case.

In 1999, Myles, then seven years into his sentence and serving as his own attorney, successfully drafted the post-conviction petition that, at least in theory, gave him another chance to fight his conviction. When the court told him he was entitled to a hearing, Myles was assigned to Marienne Branch, his third public defender.

Myles said he offered to show Branch the notes he had typed up after his conviction, chronicling what he viewed as the glaring inconsistencies in the police reports, but he felt she didn’t take him seriously. Year after year, he said, she took no action that he could see.

Branch didn’t deny failing her client, and in one interview said she feels ashamed of how she represented him.

Public defenders “did nothing for years. They would read newspapers all day. They would be gone all day.”

“I was broken,” Branch said of the time she worked at the post-conviction unit of the public defender’s office. Her daughter suffered from severe depression, she said, and “every day I’d come home from work and wonder if I’d find her hanging from the rafters.” The daughter later killed herself. Branch had a stomach surgery among a litany of other health issues and survived a fire at work that she said debilitated the office for months, on top of the crushing stress of public defense that she likens to “digging ditches every day.”

She described the post-conviction unit, made up of a handful of attorneys, as “the rest home” for burned-out public defenders. In the unit, “people did nothing for years. They would read newspapers all day. They would be gone all day.”

“For a very long time, I didn’t know what I was doing,” she said. “So I sat there. I couldn’t do anything. I used to come into work late. There’s no set hours. I would just sit there.”

A few days later she called to say she didn’t actually recall the case.

Lester Finkle, of the Cook County public defender’s office, said Branch’s account was untrue.

“She is a disgruntled former employee,” said Finkle. He claimed her case file contained drafts of motions she’d written and requests to investigators to find witnesses in Myles’ case. He declined to provide copies of any of that work to BuzzFeed News, citing client confidentiality.

In 2011, Branch took medical leave and a fourth public defender took over the case. The new attorney, Jeffrey Walker, a lawyer with Harvard credentials, filed a motion seeking Wojcik’s disciplinary history on the police force. He sent an investigator who found that Bracey, the friend whose apartment Myles says he was visiting at the time of the shooting, had died as the case sat on the docket. The investigator tracked down another man, who signed a statement saying he saw Myles leaving Bracey’s apartment at the time of the murder.

Then, earlier this year, at age 59, that fourth lawyer died of cancer, and a fifth public defender picked up the case.

But before the latest public defender dug into the case, Myles learned that Bonjean had agreed to represent him.

An outspoken and audacious lawyer who lives in New York (and strides the halls of criminal courthouses in Christian Louboutin heels), she has in the last 13 months gotten two people's convictions overturned from the same unit

where Wojcik and Guevara worked. In the case of a third, she won him the right to a new trial.

Jennifer Bonjean

Bonjean says she intends to crank Myles’ case “into high gear” by tracking down key witnesses and probing deeper into his allegations of police coercion, particularly the claims involving Wojcik — who, she says, has also been accused of misconduct by some of her other clients.

Meanwhile, Wojcik retired with a pension after having signed off on reports in which his subordinates lied about the high-profile 2014 police shooting of Laquan McDonald. A lawsuit filed by the City of Chicago Office of Inspector General — the agency conducting an internal review of the case — described Wojcik as playing a “significant role” in the police department's response to McDonald's shooting. The report he signed off on was later cited by the Department of Justice as an example of how officers possibly colluded with one another to fabricate stories and cover their tracks. He has not been charged with any crime.

Myles said that having Bonjean on the case has renewed his hopes for justice, even if his parents can’t be there to see it.

He often remembers the phone call he made more than 16 years ago, telling them he would be headed back to court.

“You’re going to straighten out your life,” he remembers his father telling him.

Myles has since worked as a baker in prison, and taken classes to help him treat his addiction and courses on understanding the causes of mass incarceration.

“A lot of times I sit and wonder what I could I have done differently that night,” he said. “And the answer is nothing.”

His case is rescheduled, again, for Aug. 31. ●