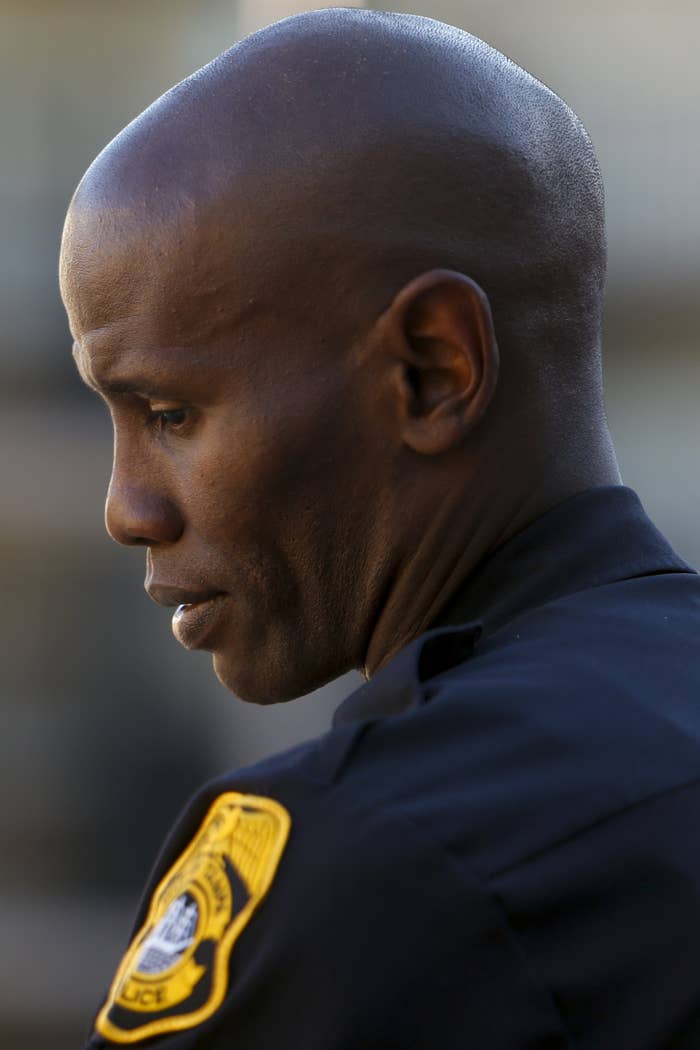

TAMPA, Florida — Officer Jerry Wyche had a decision to make.

On the night of Jan. 1, 2018, his colleagues had stopped three Black teenagers at a Tampa gas station for driving with their lights off. A search revealed an illegal gun and a gram of cannabis. A 17-year-old boy was arrested. Many people would call that a success.

But Wyche, a 10-year veteran of the force, called it “bullshit.” He believed his colleagues had cut corners to conduct the search.

In the official report, officers wrote they had probable cause to search the car because they smelled cannabis. But Wyche hadn’t noticed any odors when he looked in the car that night. He remembered hearing the lead officer say he planned to ask the driver for consent to search — a constitutional requirement when cops don’t have probable cause — but the report made no mention of asking for consent.

Wyche, who is Black and carries himself with the posture of a former Marine, had joined the agency as an idealistic 28-year-old, confident in his ability to change policing from the inside. Now, he believed, he had a duty to speak up.

Friends warned he might face backlash for reporting his suspicions and counseled him to let it go. Did he really have enough evidence? What would he achieve from drawing attention to such a seemingly minor and murky case?

Besides, Wyche had worked hard to reach his position. He had recently been selected for the elite SWAT team and was featured on a TV show about first responders. In evaluations, he was consistently praised for his ability to get guns off the street, his speed chasing down criminals on foot, and his skill as a mentor. “Not only is Officer Wyche an extremely hard worker, but his character, integrity, and loyalty to the Tampa Police Department should be recognized as a top-notch police officer,” a supervisor had written in his review two years earlier. Why mess with that?

But in Wyche’s mind, it was a matter of principle. He imagined the teenagers facing the police version of events in court, their distrust of cops and the judicial system cemented. “We’re no better than the criminals if we bend or break the law for one arrest,” he said.

For months, he had trouble sleeping. His mind kept replaying the movie Detroit, which features a Black security guard who attempts to play peacemaker in a volatile situation but winds up helpless to stop the brutality of white police officers. He recalled the words a stranger on the street had recently yelled: “You see the white officers fucking with us, and you’re just as bad as they are if you don’t speak up.”

On April 26, 2018, the day before Wyche’s 39th birthday, he sat down with the agency’s internal investigators and shared his concerns. It was the most difficult thing he had ever done, he later said. At one point in the interview, he cried.

“It’s hard going out there and knowing I have this on my chest,” he told them, according to transcripts. “People hate us enough — we gotta be able to police ourselves.”

Wyche faced a tension familiar to many Black officers who know the toll of racial profiling from experience and feel the burden of representing their communities while in uniform: He was a minority in a police department with a legacy of mistrust in Black neighborhoods, trying to be part of the solution.

BuzzFeed News interviewed 20 Black current and former Tampa police officers, who described an internal culture at the Tampa Police Department that pushes Black officers out of the profession and perpetuates police tactics that have left the city’s Black residents overpoliced and underserved for decades. A review of court documents, department records, discrimination complaints, and employment data corroborated the officers’ accounts.

“They've had a good ol’ boy system right inside the police department,” said Darrell Johnson, a Tampa officer from 1990 to 2011, echoing comments from Wyche and at least three current officers. “It's not going anywhere, it just changes with time.”

Officers said that that “system” is made up of veteran white middle managers and trainers who influence promotions, discipline, and tactics, and seem to endure every change of leadership.

“If you are ‘in’ with certain people, you can do whatever and it never sees the light of day,” Johnson said, a perception current officers also shared.

Most officers expressed pride in the careers they had built, as well as gratitude for a job that supported their families and, on the best days, filled them with purpose. But 15 Black officers, some of whom requested anonymity for fear of losing their jobs, said they were often frustrated to witness white officers disrespect Black residents, misinterpret cultural cues, and express stereotypes that contributed to unequal policing.

Wyche said it demoralized him to hear some white officers refer to community policing efforts as “hug-a-thug” or share negative comments about women dealing with domestic violence. One officer he worked with called Black people at a club “animals who should be caged,” he said. Another joked he would “shoot any Black man running” while they were patrolling for a serial killer, he said. It seemed to him that too many of his colleagues focused their energy on low-level arrests and viewed Black neighborhoods as dangerous places that primarily needed to be controlled, not assisted — and there was no simple way for him to stop that.

Still employed by the department, Wyche agreed to extensive interviews with BuzzFeed News and a review of his own missteps and discipline history. Over the course of months, he shared internal investigation files, official documents, and correspondence related to his discipline cases and discrimination complaints, as well as emails, text messages, photos, and body camera videos. BuzzFeed News also obtained his personnel files and spoke with family members and former and current colleagues.

Sharing a window into his experience publicly, Wyche said, feels like a chance to contribute to the national conversation around policing and influence the system for future generations.

“The community has been screaming for change for years,” he said. “It has to be yelled not only from the outside but also from within.”

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020, people across the country filled city streets, marching to chants of “defund the police.”

But by 2022, with rising crime rates fueling anxiety, local officials and President Joe Biden have largely rejected that call. The future of American law enforcement, it appears, rests on the ability of police forces to reform themselves from within.

The Tampa Police Department, a midsize agency in a diverse Southern city, is emblematic of that challenge.

For decades, the department has engaged in “proactive policing” — the prevalent crime reduction strategy at law enforcement agencies across the country. The philosophy, which took hold during the war on drugs era of the 1980s, promotes aggressive enforcement, encouraging officers to use traffic stops and minor violations in high-crime areas as a means to search residents for drugs or weapons. Data analysis often finds the tactic does little to improve public safety. Instead, it leads to racial profiling, acts as a gateway to mass incarceration, and contributes to increased killings by law enforcement.

Tampa’s low-income Black neighborhoods have felt the brunt of that strategy. More than half of those arrested by Tampa officers annually are Black, though Black people make up less than a quarter of the population — a disparity that has remained consistent for at least the past decade.

Police initiatives have disproportionately targeted Black residents, Tampa Bay Times investigations revealed. From 2009 to 2016, 80% of those ticketed in a bike citation program — which the federal government later deemed ineffective in fighting crime — were Black. Ninety percent of those evicted through a recent program aimed at reducing crime in low-income apartment complexes — sometimes triggered by misdemeanors or charges that were later dropped — were Black.

Recent research suggests that police departments with more Black and Hispanic officers lead to fewer use-of-force incidents, traffic stops, and arrests — particularly in neighborhoods of color. As far back as the 1980s, mayors have promised to advance diversity at the Tampa Police Department, touting mentorship programs and recruitment strategies.

Over the course of a generation, those efforts have barely made a dent.

In 1987, the force was 10% Black. In 2020, it was 12%, compared to 22% of the population. Overall, nearly 70% of Tampa officers are white, compared to only 43% of the city, according to agency data.

“I am one of those people who believes I control my own destiny,” said Reginald James, a current Black sergeant in Tampa with more than 22 years’ experience. “But there’s a lot of discrimination in our department.”

Former Tampa mayor Sandra Freedman, who in the 1990s attempted to overhaul the force and boost diversity after the police killings of three Black men set off riots, said the agency’s internal culture proved her biggest roadblock to reform.

“Every department has good officers — people who want to make change in their communities,” Freedman told BuzzFeed News. “But they are stymied at every turn by people who want to cut corners.”

The agency says it has made efforts to move away from policies that result in racial profiling. Both the bike citation program and the crime-free housing program were discontinued. Arrests overall have decreased significantly over the past decade, according to data compiled by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.

Mayor Jane Castor, a former Tampa police chief who oversaw the bike citation and housing crime programs, declined interview requests from BuzzFeed News and did not respond to a list of questions and statements included in this story.

In March, she appointed a new police chief: Mary O’Connor, her former assistant chief at the agency who retired in 2016 to work as a consultant and trainer.

O’Connor rose up through Tampa’s ranks at a time when sexual harassment was considered common on the force and told BuzzFeed News she recognized some of the Black officers’ frustrations. She declined to comment on the actions of previous administrations but promised a fresh start under her leadership and said the George Floyd protests had “changed the ball game” when it comes to responding to the needs of the community and officers’ mental health.

“I know what it’s like to be in the minority in a white, male-dominated profession,” she said. “For officers like Jerry Wyche who want to see positive change, in the future, there will be a lot of opportunities to have their voices heard.”

So far, she has been attending listening sessions with Black clergy members and created a suggestion box to solicit feedback from officers. She said she is working on ramped-up recruiting initiatives as well as wellness support and diversity and language training for officers.

Implementing change from the top, she acknowledged, comes with challenges. “You have to get proper buy-in,” she said. “A lot of things can get lost to translation.”

Wyche and other Black officers said they support O’Connor’s goals but are watching to see if she will be effective.

“I know she wants to do new things and try different approaches, but we’ve still got the same like-minded individuals in leadership,” Wyche said. “I just hope she does try to get that old boy’s mentality out of here because obviously, it’s not working.”

Wyche knew what it felt like to be profiled.

Decades ago, he was driving around Tampa with friends: three young Black men, out for a night on the town in a champagne-colored Mazda Millenia.

A Black officer pulled him over, then searched him. At least two more police cars pulled up to the scene, he recalled.

Humiliated, Wyche asked the officer why. He remembers her saying, “It looked like you didn’t belong in your car.”

The experience, and others like it, didn’t stop Wyche from becoming a cop.

Other people could sit on the sidelines and complain, he liked to say. Wyche wanted a seat at the table.

Raised in the Tampa suburbs by a single mother who had fled an abusive boyfriend, Wyche grew up with dreams of joining a brotherhood of higher purpose. He looked up to the cops who mentored him at an after-school program and brought him home after he drove a borrowed car into a ditch at 16. He credited them with helping him avoid the path of relatives who struggled with addiction or got into drug dealing, and he hoped to do the same for others.

He joined the Tampa Police Department full time in 2008, then went undercover for the narcotics squad, served on the Honor Guard, and worked with the plainclothes violent crimes unit. He often referred to the agency as his “family.”

But his idea of good police work sometimes clashed with the agency’s priorities.

Early in his career, he came to understand how easily bias could creep into police work, even his own.

In his first year patrolling a low-income, majority-Black neighborhood, he was on high alert to identify those involved in recent shootings or robberies. At the time, the agency judged officers on metrics: Productivity reports cataloged each ticket, arrest, or interaction and spit out a ratio that was used to measure success at yearly reviews (the practice has since been discontinued at yearly reviews, the agency said).

So he focused on “pretextual stops” — finding reasons to pull over cars driven by young Black men who might be connected to the crimes — and ignored older drivers or white people. Then he noticed the habit stuck when he worked in other neighborhoods.

He vowed to be more rigorous and to never become like the cop who had profiled him.

What he saw in Tampa’s lower-income communities were people who were overpoliced yet underprotected, living with the constant fear of shootings and robberies but reluctant to share information with officers they mistrusted. If he wanted to get to the root of the neighborhood’s issues, he knew he had to work harder to build relationships that would help solve major cases of wrongdoing, instead of chasing every small drug charge he could find.

He remembered the first time one of his arrests — a man caught carrying a baggie of crack cocaine — led to a federal conviction. With supervisors congratulating him, Wyche had felt proud.

Then he learned the man’s prison sentence: 21 years. The number stopped him cold. He pictured the man’s children. What good could come of so many years locked away?

He couldn’t change the laws, but at that moment he decided to focus his energies whenever possible on educating people rather than arresting them.

Six years into Wyche’s career, protests against police brutality began to fill streets across the nation. Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Alton Sterling, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, and others killed by officers became household names.

Wyche knew what it was like to face a volatile situation with your finger on the trigger. In one bodycam video reviewed by BuzzFeed News, he points his gun as a fleeing man puts his hands behind his back — a movement that Wyche believed supervisors would interpret as reaching for a weapon. Wyche didn’t shoot. A second later, the man revealed his hands: empty.

So he understood the outrage against police actions that seemed driven by unconscious bias. But he also wanted to show the public his perspective that not all cops are so quick to use violence. In 2017, with the agency’s support, he was featured in the A&E docuseries Nightwatch, which aims to “chronicle the sacrifice and heroic work of the first responder.” The show captured him searching for armed robbers in dark alleys and calming a Black driver’s nerves during a traffic stop.

On Snapchat and Instagram, Wyche began sharing personal snippets from his life and work, like dancing in the car with his partner or making blueberry pancakes with his teenage son. It was an entryway to dialogue: Young Black men and women sometimes messaged him with questions about police conduct or to tell him they appreciated the way he talked to people on the show. Some asked for help deciding if policing could be a career path for them.

Around that time, Taylor Randolph, a Tampa activist involved in Black Lives Matter protests, came across his Snapchat feed. Under a photo of Wyche with a little girl, he’d written: “My job is to keep people out of jail. Help motivate them to be great young so they won’t get arrested older.” Intrigued, she followed him.

At first, Randolph found many of his posts irritating. When he talked about police misconduct cases across the nation, he defended the institution and blamed “bad apples.” She was repelled by his earnest #BacktheBlue hashtags, she said.

She started messaging Wyche on Snapchat. In screenshots of those messages she shared with BuzzFeed News, she sometimes ranted about police cases in the news, calling him a “Pig Cop.”

Their conversations got heated, but neither backed away. Randolph’s son had recently started driving, and she appreciated hearing Wyche explain his approach to traffic stops. She grew grudging respect for him.

“He is the kind of cop that cops should be,” Randolph said. “If there were more of them, the United States would be a far better and safer place for people who look like me.”

Still, Randolph believed American policing was rotten from the inside, tainted by its role in upholding slavery and its legacy of racism. She couldn't understand how Wyche was able to reconcile his identity and his work in a system that fueled the mass incarceration of Black people. In her view, policing could only be fixed by outside pressure.

Wyche recognized the legal system was “fucked up,” he conceded in his messages. Every day he put on the uniform knowing it was a symbol of oppression, he said, but he used that energy to motivate him.

“I had a choice, be angry and bitter or do something,” he told Randolph one day. “I became a cop to make a difference.”

On the night of the traffic stop he later reported, Wyche recalled pulling up to a Shell gas station at around 10 p.m. and saw his SWAT squadmate Nathan Toole talking to the teenage driver of a gray Toyota Camry.

A former high school football star in nearby Hudson, Florida — a city of about 12,500 people that is more than 91% white — Toole had signed up for the police academy after an injury ended his collegiate sports career, according to a Tampa Bay Times article.

He joined the Tampa Police Department in 2011 and made the SWAT team on his first try in 2014, personnel files show. His supervisors soon encouraged him to “start to study for the next promotional exam.”

He has no major discipline cases in his file and excelled at the agency’s metrics on proactive policing, evaluations show. In his first three years on the force, Toole investigated 1,235 “quality of life” complaints — minor infractions that can include noise, loitering, or public intoxication — and made arrests in 92% of them. He was assigned 2,547 calls for service but initiated 10,999 on his own.

“Officer Toole is extremely active and seizes all opportunities during patrol,” a supervisor wrote. “Although he is a relatively young officer, he has shown that he is willing to put the department’s objectives ahead of his personal desires.”

Reached by phone, Toole declined to speak to a reporter without agency approval. The police department did not make him available for interviews.

“We’ve got a spike in gun and violent crime and this is a really good cop that is making the community safer,” said Adam Smith, the mayor’s spokesperson.

After arriving at the Shell gas station, Wyche peeked his head into the car and saw three Black teenagers sitting quietly and looking scared.

He later told investigators he heard Toole say, “they’re clean”— meaning there were no warrants in the teenagers’ names — “I’m trying to get consent to search.”

For a consent search to be legal, a driver must feel free to leave at any time. To Wyche, that meant turning off emergency lights, returning the driver’s license, and making sure officers weren’t crowded around. He usually made it clear by saying, “You’re free to go,” before asking, “Do you mind if I search the vehicle?”

And yet, after Wyche walked back to his car, six of his colleagues remained in position around the Camry. Wyche snapped a photo on his phone to send to another Black officer.

“I guess this is the new consent search,” he remembered writing in a text message.

After Wyche reported his concerns to Internal Affairs, investigators interviewed the 18-year-old driver, My’Tia Pegues, and the owner of the car, Ebony Anderson, who was not at the scene.

According to transcripts of her interview, Pegues told investigators that when Toole asked to search, she said she was uncomfortable. She had just taken a high school course in crime studies and knew her right to refuse a search, but the officer kept insisting, she said.

So she called Anderson, her boyfriend’s mother, and passed the phone to the officer. When he hung up and ordered everyone out of the car, she assumed Anderson had consented.

But Anderson told investigators she never agreed to a search. She remembered the officer saying on the phone, “I’m just letting them go, it’s no big deal.” When she couldn’t reach her son or Pegues on the phone, Anderson went to the scene and found officers arresting her son for a gun they had found in a backpack.

When she asked why the car was searched, Toole mentioned smelling cannabis. That didn’t make sense to her, she told investigators. She asked why he hadn’t mentioned it on the phone.

Pegues told investigators she was also confused by the cannabis explanation, which came after the search was already conducted.

Yet the investigators omitted Pegues’ and Anderson’s skepticism and summarized their interviews this way: “Both subjects recalled the Officer mentioning the smell of marijuana in the car as the reason for the search. During the interviews, neither subject accused the Officers of any wrongdoing.”

Investigators were unable to retrieve video from that night. They didn’t interview any of the other six officers who were at the scene and instead relied on their depositions given to the arrested 17-year-old’s public defender.

Those depositions do not lay out a full timeline of events. Toole and his partner described smelling cannabis while questioning the teenagers. Toole said he touched his ear or nose to send a nonverbal cue to his partner about the cannabis smell. His partner described smelling it herself, then searching the car. They both said Toole called Anderson after the 17-year-old was in handcuffs — a contradiction to both Pegues’ and Anderson’s memories.

But the investigators decided the officers’ depositions were consistent with the report and closed the case. The agency declined to comment on the investigation. When BuzzFeed News requested a list of internal investigations for the past 10 years, it was not included. The agency said it was “reclassified.”

Keith Taylor, a former New York Police Department detective sergeant who supervised SWAT and Internal Affairs units, reviewed the investigation for BuzzFeed News. He called the differing accounts of the interaction “a very clear red flag of an attempt to cover up behavior that is not compliant with the agency’s policies.”

He was unable to draw any conclusions from the investigation, he said, because it was incomplete. If he were overseeing it, he’d reinterview the officers instead of relying on their depositions to explore any inconsistencies and would likely pass the review to an independent entity, like the state attorney’s office, he said. At the New York Police Department, he would also have recommended integrity tests designed to see how the officers respond in similar situations.

“This is a very serious matter because it involves intimidation and the loss of the rights of the persons that were stopped,” he said. “The tolerance for official misconduct or corruption is laid bare for the officer who made the complaint, as well as the individuals in the car. That has to be addressed in a forceful way.”

Chief O’Connor said she supported Wyche’s decision to report the incident but declined to review the investigation because it occurred prior to her leadership. “I have to trust that professional standards were the same then as now,” she said.

Contacted by a reporter, Pegues said she had never seen the 17-year-old, her boyfriend, get in trouble. She remembered him desperately repeating “junior, junior!” to make sure officers didn’t confuse him with his father, who has the same name and a long criminal record. The boy’s charges for being a minor in possession of a concealed firearm were ultimately dropped. Efforts to reach Ebony Anderson for this story were unsuccessful.

Pegues said she had not understood her interview was part of an internal investigation into the search. She was surprised to learn there had been no consequences. Asked how she felt about Wyche’s decision to report the incident, she said, “I’m glad he couldn’t sleep. He should have said something when he snapped that photo.”

When Wyche received the letter the following August notifying him of the investigation’s conclusion, he felt like a target had been placed on his back.

Police officers who speak up against colleagues often face retaliation. Last year, reporters for USA Today identified 300 examples of officers who had reported misconduct over the last decade and found all of them were eventually forced out of their departments. Some received death threats or dead rats in their lockers. Others had their requests for backup ignored or soon became entangled in discipline cases.

Wyche already had a blemish on his record. In March, he had received a written warning — his first major one — after weapons were stolen from his police vehicle.

He had been using a loaner van that lacked a lockbox key while his usual car was in for repairs. He left his weapons in the car parked outside his house because he didn’t want to have guns inside with his son around, he said — but that violated policy. Supervisors also verbally warned him about his social media usage, saying they worried that his posts had led to his car getting burglarized, though they produced no direct evidence.

A week after the traffic stop investigation closed in August, Wyche got into trouble again. At an elementary school presentation, he put his gun’s magazine in a basket on the teacher’s desk, worried the excited children might try to grab it from his pocket as he moved around the classroom. Then he forgot about it. When an employee found it the next day, the school went into lockdown.

In the wake of his second violation in one year, Wyche was kicked off the SWAT team.

He took it hard. The squad had represented a high point of his career dreams, and he saw it as punishment for speaking out.

He couldn’t stop obsessing over all the little details and feelings of betrayal that had led up to his expulsion. The way a teammate he didn’t know very well had complained to supervisors about his social media accounts instead of talking to him directly. The time a colleague told him other officers were “gunning” for him. How his bosses said there weren’t any replacement weapons to give him after his were stolen — but how then, months later, they had weapons to give new recruits to the team.

He knew he had made mistakes, but he also worried the scrutiny and discipline were signs of a deeper exclusion — that supervisors were building a pattern of incompetence that could lead to termination.

The way he began to see it, he had given everything to the department, yet his SWAT “family” had turned their backs and discarded him as soon as he spoke up about the rights of Black teenagers.

He gathered all those indignations into a discrimination complaint he filed with the state, alleging that, as one of two Black men on the SWAT team, he was singled out for social media monitoring, retaliated against because he had reported a teammate to Internal Affairs, and never reissued service weapons after his were stolen, putting him in danger on the job.

Discrimination cases are difficult to win without an unmistakable, documented case of inequity or a clear pattern over time. Wyche had a collection of perceived selective treatment. The city responded with its own interpretation of those incidents, including that eight years earlier a white SWAT member had been kicked off the team for inappropriate social media conduct. His infractions included posts that showed him drinking while driving a boat, among 10 other incidents that displayed “an egregious pattern of behavior.”

Wyche’s discrimination case was dismissed.

His troubles continued. The next year, Wyche’s gun accidentally discharged in its holster while he was exiting his car.

Wyche was kicked off plainclothes and undercover work and sent back to work overnight shifts responding to nonstop calls in the agency’s bottom ranks. He filed another discrimination complaint, but that didn’t go anywhere either.

Colleagues believed Wyche’s treatment stood out.

“For the last couple of years, they have been on his back — every time he did something they thought was wrong, they would go after him severely,” said James Dausch, a retired white officer who worked with Wyche on the Violent Crimes Unit. “To me, he is an excellent officer and now he’s getting a reputation as basically screwing up and getting in trouble for stuff other people don’t get in trouble for.”

Wyche’s current supervisor, Reginald James, said he believes leaders like former chief Brian Dugan were looking to push Wyche out.

“As a police officer, he is very, very good and shouldn’t be having the type of problems he’s having,” James said.

The agency declined to respond to questions about the case or Wyche and others’ characterization of his career. Dugan, who retired last September, said he had lost confidence in Wyche because he felt he didn’t take responsibility for his mistakes. He confirmed that in a meeting, he called Wyche “incompetent” and an “embarrassment to the department.” When asked if he thought Wyche should be on the force, he said: “It’s probably good for him that I’m gone.”

Meanwhile, in 2019 Toole was promoted to corporal. The agency posted a video of one of the ceremonies with a caption celebrating “18 of the best and brightest.”

Sometimes, Wyche confided his frustrations in Randolph, the Black Lives Matter activist. The relentless optimism that had initially annoyed her was wearing thin. “It probably hurt him quite a bit to find the thin blue line only runs so deep, and at the end of the day, he is Black,” she said.

Last June, Wyche was driving down Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, turning over his job issues in his head, when he lost control of his car and crashed into an iron rod. It slammed through the window, barely missing him. For the first time, he called the agency’s mental health hotline. He wondered how much longer he would stay on the force.

Wyche’s social media accounts are private now. Last year, feeling fed up, he posted a rant on Instagram:

The good old boy system is stronger than ever. Because it’s allowed to thrive. It can be killed, but they won’t. Because that means you have to treat everyone equally. That’s not ever going to happen unless the cowards resign or you make them feel uncomfortable. Stand together and call them out on their BS.

Over Snapchat, Randolph, the activist, wondered why he didn’t quit.

“How can you survive in such an institution, with the trauma that comes along with it?” she asked him.

But after all he had seen, he still felt tied to his commitment. He thought of the young girl who approached him recently in the courtyard of a public housing complex to ask, “When someone goes to jail, are they a bad person?” He recognized her and knew her mother had recently been arrested.

“No,” he explained. “They’re not a bad person. They just made a bad decision.” It was a well-worn phrase Wyche often found himself needing to repeat to children in the neighborhood. (BuzzFeed News spoke to a witness who independently verified his account.)

To Randolph, he replied: “My currency doesn’t reside in the department. It resides in the community I’m fighting for.”

Wyche still works the overnight shift. After Dugan left, he continued to raise questions about his treatment and about racial discrimination in the department. In a meeting, Assistant Chief Lee Bercaw encouraged him to put those questions behind him and “focus on moving forward,” according to agency records. In January, supervisors invited him to become a part-time field training officer.

In that role, he takes new recruits out with him to meet kids in the community and believes he can make an impact by inspiring the next generation of Tampa officers to see the people they police as residents who “deserve respect,” as he puts it, not a population that needs to be controlled. But he doesn’t see how he can “just move forward” from the discrimination issues he raised without seeing any accountability.

This winter, Wyche sat down with his 16-year-old son to have “the talk” before he started driving.

He had always tried to shelter his son from the realities of policing. The two have never spoken about George Floyd’s murder. But Wyche worried that if his son gets pulled over one day, an officer might only see a young Black man with dreads, not necessarily the goofy teenager just breaking out of his shell, who loves anime and dreams of becoming a computer engineer.

He could imagine his son getting nervous in a traffic stop, asking “why” over and over, like he does at home. He feared how easily things could escalate.

So in February, he told his son what he knows: that not all cops are good. That a Black teenager in America can’t count on the same treatment a white teenager gets. He reminded him to follow directions and keep quiet, even if a cop is unfair — so he can make it home safe.

When he ran out of words, his son had a question: “Why does it have to be this way?”

Wyche told him: ”I’m still trying to figure that out.”

On a recent afternoon, Wyche clocked into work at 3 p.m., ready for another overnight shift. A corporal soon called for backup at a fast-food restaurant, where he wanted to check on a group of men he noticed gathered outside.

He headed over. According to body camera video, the manager explained she had given the men permission to be there — she gave them food in exchange for cleaning the parking lot and keeping watch, and they had once alerted her to a break-in attempt. But the corporal wasn’t satisfied and made it clear the men needed to leave, Wyche said.

Wyche found the whole thing a waste of time and resources. The men weren’t bothering anyone, no one had issued any complaints, and now here were more people who felt the cops were harassing them instead of working on bigger problems.

But he didn’t see any use in complaining or reporting the incident. He didn’t think it would change anything.

“I know this is wrong,” Wyche later recalled, “but I can’t say it’s bullshit.” ●