Long before he became Donald Trump’s feared attack dog, or began to visit the White House as the president’s personal attorney, or took a position with the Republican National Committee, or partnered with powerhouse lobbying firm Squire Patton Boggs, Michael Cohen ran a small legal practice in Hell’s Kitchen.

He was a one-man show and handled a little bit of everything, from personal injury cases to a Ukrainian investment fund to a fleet of taxis to a trust account he managed for clients.

One day in 1999, a check for $350,000 was deposited into that trust account, to be disbursed to a woman living in South Florida. As the lawyer in charge of the account, Cohen was supposed to ensure that she got the money.

But he didn’t.

Why not? And what ultimately happened to all that money?

“I don’t recall,” Cohen said in a deposition.

The missing $350,000 — which has never been recovered — became the centerpiece of a 2009 lawsuit in Miami, where Cohen was accused of civil fraud. After years of litigation, Cohen prevailed, in part because the suit was filed past the statute of limitations.

Cohen, in an interview with BuzzFeed News, said he was first questioned about the money eight years after it was deposited, by which time he said he could not recall much about it. “I honestly don’t remember who gave me the deposit at the time,” he said. “This is another poor attempt to malign my impeccable reputation and attempt to connect me to a Russian conspiracy.”

But Cohen’s own testimony in the case reveals that the man who is now the president’s personal lawyer failed to execute one of the core duties of an attorney — properly handling money placed in his trust — and was cavalier about that failure.

“One of the things lawyers are most likely to be disciplined for is misusing clients’ funds,” said Deborah Rhode, a legal ethics expert from Stanford University, who said that properly accounting for and disbursing funds is a critically important obligation for many attorneys.

“A lawyer who, incident to his law practice, comes into possession of funds belonging to a client (or third person), has very clear obligations,” Stephen Gillers, a professor at New York University, wrote in an email. Like Rhode, he declined to comment on the particulars of Cohen’s case, which he was not familiar with, but said that in general a lawyer “may not commingle the funds with his own. He must keep them in a separate account, sometimes called an escrow or special account. He must ‘promptly’ notify the client or third person of his receipt of the funds and ‘promptly’ deliver them.”

“This is another poor attempt to malign my impeccable reputation and attempt to connect me to a Russian conspiracy.”

New York State Bar Association records show that Cohen has never been disciplined. A spokesperson for the association said cases that were investigated but resulted in no discipline are kept secret.

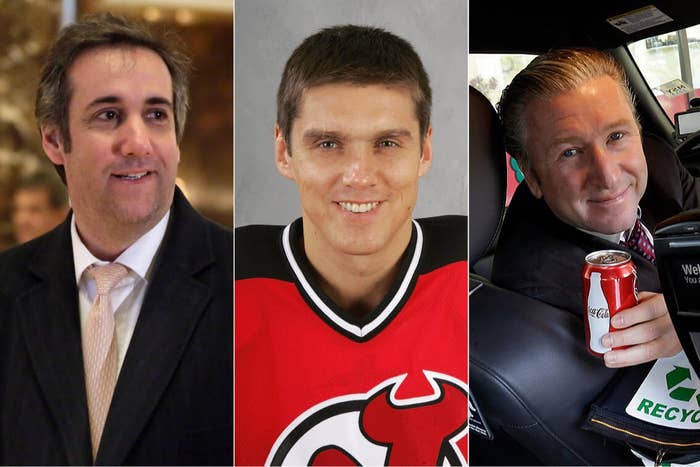

The $350,000 mystery involves four other important characters: Vladimir Malakhov, a professional hockey player who wrote the original check; Yulia Fomina, a Russian woman who asked Malakhov to loan her the money and put her condominium up as collateral; Vitaly Buslaev, a Russian businessperson who was Fomina’s boyfriend; and Symon Garber, a Ukrainian-born taxi baron who was Cohen’s business partner.

In 1999, Malakhov was playing defense for the Montreal Canadiens. He would play in the NHL for a decade, win a Stanley Cup, and collect about $30 million in salary. Along the way, he attracted the attention of Russian organized crime. During Senate hearings, a former gangster testified that someone tried to shake down Malakhov at a restaurant in Brooklyn’s heavily Russian neighborhood, Brighton Beach. The man who made the threats reportedly worked for Vyacheslav Ivankov, a notorious Russian mafia boss who was later assassinated in 2009.

“Malakhov spent the next months in fear,” according to the testimony, “looking over his shoulder to see if he was being followed, avoiding restaurants and clubs where Russian criminals hang out.”

Malakhov was playing for Montreal in 1999 when Buslaev and Fomina entered the picture.

Yuri Felshtinsky, a Russian-American historian, reports that Buslaev was dating Fomina and supported her in the United States, helping her purchase a condominium, an Aston Martin, and a Mercedes-Benz. There are few public records available on Buslaev, but Russian business registrations show him as a manager of at least three companies near Moscow.

Court records show that around that time, Buslaev encouraged her to ask Malakhov and his wife, with whom she was friendly, for a loan.

Buslaev was looking for a hedge against “the instability of the Russian ruble on the foreign exchange market,” Malakhov’s sports agent wrote in an affidavit. At the agent’s suggestion, Malakhov demanded some collateral. (The agent, Paul Theofanous, did not return a message left at his office last week.)

So Fomina put up the deed to her condo and Malakhov wrote the check.

But he didn’t write it to her. At what he would later say was Fomina’s request, Malakhov wrote it to the trust account that Cohen controlled.

Two years later, claiming that Fomina failed to repay the loan, Malakhov’s wife went to court to take possession of the condo.

Fomina was in Russia at the time. When she returned to Florida, she filed suit, claiming she had been taken advantage of and didn’t speak enough English to understand the loan documents she signed. She and the Malakhovs did not return phone calls seeking comment, and Buslaev could not be reached. But Fomina’s lawsuit set off more than five years of litigation, and Malakhov’s lawyers eventually questioned Cohen about his role in the matter.

Got a tip? You can email trump@buzzfeed.com. Or go to tips.buzzfeed.com to learn how to reach us securely.

During a deposition, they showed him the check that Malakhov wrote, which had been endorsed with what appeared to be Cohen’s signature. Cohen declined to say whether it really was his.

“It could be,” he allowed.

He said that he didn’t know Malakhov, Fomina, or Buslaev.

The trust account, he explained, was used for “negligence settlements” or “property damage claims.” Perhaps the money was meant for the Ukrainian investment fund he managed, Cohen said.

Again and again — at least six times — Cohen said he didn’t recall why the $350,000 was deposited or what became of it.

Because many of the players in this deal were Russian or Ukrainian, lawyers pressed Cohen about his connections to those countries. He said that he had visited “Russia or the Ukraine” in the past but that he never sent money from one of his business accounts to anyone living there. He said that he had foreign clients and partners, including Garber, who helped him manage a fleet of taxis in America. Garber was listed as a witness in the case but was not interviewed by attorneys. Visited recently by reporters at his taxi headquarters in Queens, Garber declined comment.

“Somewhere along the line, I was asked to hold somebody’s funds for whatever the purpose was,” Cohen said during his deposition in 2007. “Whether it was A, B or C, I don’t know the reasons and I can’t even begin to guess.”

The money, according to court filings, has never been found.

CORRECTION

Paul Theofanous is a sports agent in New York City. A previous version misspelled his name.