NEW ORLEANS — After Hurricane Katrina, Princess Dennar made history as the first Black woman to run a physician residency program at Tulane University.

In 2020, she made history again, this time by suing Tulane for racial and gender discrimination. Her white male bosses had “subverted” and “actively undermined” her leadership for years “to force her to resign,” she alleged, and young Black women training under her were suffering the consequences.

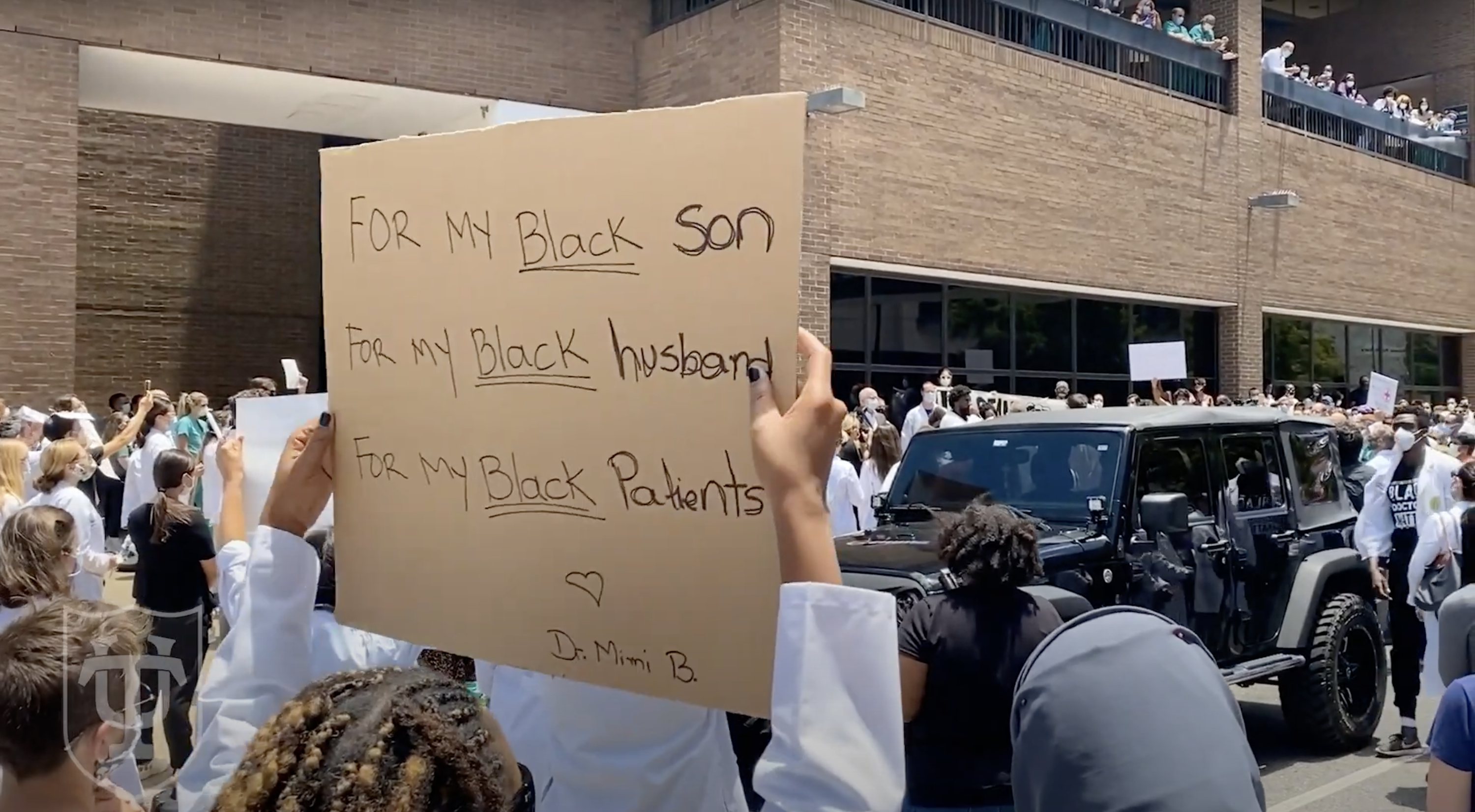

As protesters demanded justice after George Floyd’s murder, as cities tore down Confederate statues, as health agencies declared that racism kills, Dennar hoped that she could force one of the oldest medical schools in the Deep South to confront its dark past. And maybe she could call attention to her profession’s failure to reflect the people it cares for. Just 5% of doctors and 3.6% of medical school faculty members nationwide are Black, compared to 13% of Americans and 60% of New Orleanians.

By going public with their collective experiences, Dennar and her trainees set out to test the reach of America’s supposed racial reckoning. They would learn firsthand how difficult institutional racism is to prove — and even harder to fix.

“When discrimination happens, most times, it’s not going to be somebody saying a particular word,” said Ruqaiijah Yearby, a legal expert in racial health disparities at Saint Louis University. “It’s about the power to be able to put people in a less equitable situation.”

According to Dennar, her boss, Jeffrey Wiese, undermined her authority by controlling her trainees’ schedules and threatening to shrink her program while mandating use of an algorithm that effectively shut out applicants from historically Black schools. She also accused the medical school dean, Lee Hamm, of failing to protect her from that alleged discrimination, making inappropriate remarks about her race, and retaliating against her for complaining. Seven of her Black residents, nicknamed the Tulane Seven, told the university that Wiese overburdened them with difficult shifts and deprived them of opportunities given to white residents. One of the seven launched a discrimination lawsuit of her own. So did a third Black woman.

If you have tips related to race and racism in academia or medicine, you can contact this reporter at stephaniemlee@protonmail.com.

Concerned about “serious allegations of racial bias and discrimination,” a national accreditor put Tulane on probation, jeopardizing its license to train residents. A survey revealed that many others on campus saw their leaders as detached from “the reality of gender and racial inequities” — and prone to punishing victims of harassment and racism. And a viral social media campaign inspired applicants to boycott. All of this made the Black women hopeful that progress could be on the horizon. Now it is up to Tulane to see that it happens.

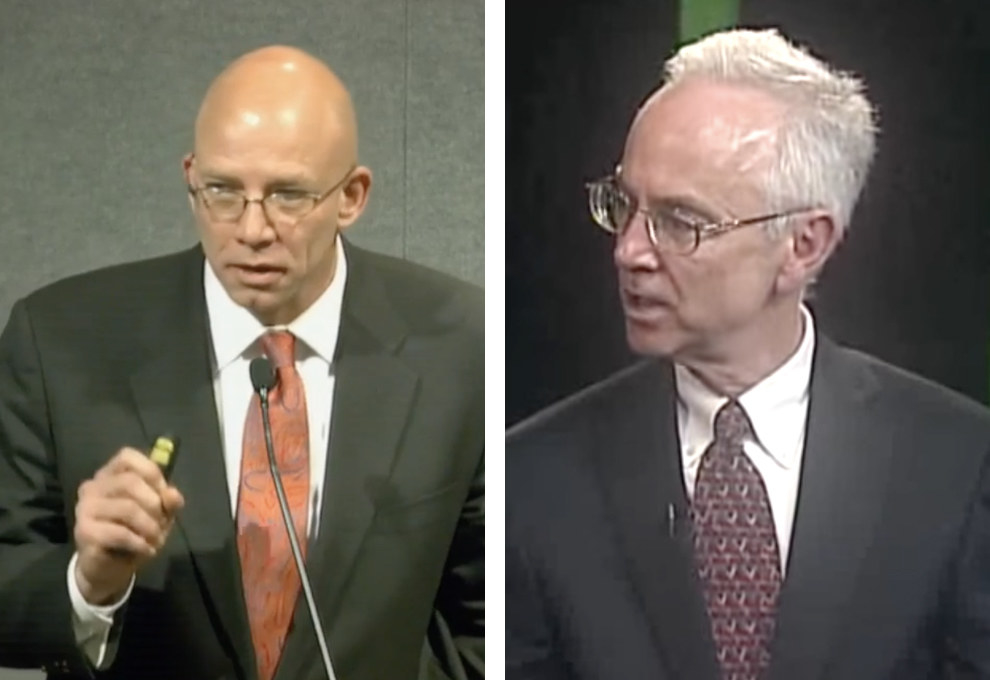

Wiese, 52, and Hamm, 69, did not return multiple requests for comment for this story, which is based on interviews with more than a dozen former residents and six current and former faculty members, as well as more than 1,000 pages of court records, emails, and internal documents. In a court filing, Wiese denied that he ever discriminated against anyone based on race or gender.

“We fully recognize that Tulane School of Medicine has more work to do to create a truly welcoming, equitable, diverse and inclusive academic and clinical community,” said Tulane spokesperson Michael Strecker, who added that he could not comment on the lawsuits’ claims. “We value every member of our community and recognize the contributions of all, including Black female doctors who enhance the quality of our medical education and care.”

In February 2021, with her lawsuit pending, the university removed Dennar, 46, from the directorship that was once her dream job. Despite being demoted, she could still be a force for good, she told me as we walked through the French Quarter that October. “Why do I stay there?” she said, looking at me through cat-eye frames. “Because I think there’s still work to be done.”

Two months later, she left for good.

In the wreckage left by Katrina, New Orleans’ fragile healthcare infrastructure looked irreparably broken. Reeling from damages totaling nearly $1 billion, Tulane watched one-third of its medical school faculty leave, part of a citywide exodus of doctors. Charity Hospital, the public safety-net hospital that for centuries had served people living in poverty and without insurance, was gutted. Tulane’s doctors-in-training suddenly found themselves needing to train elsewhere, maybe permanently.

Wiese, who ran Tulane’s adult internal medicine residency program, jumped into a Chevy Silverado with a mission. On a 36,007-mile road trip in fall 2005, he personally visited each of his 105 trainees to try to persuade them to return. “I wanted to be able to look in their eyes and say, ‘I still believe,’” Wiese told the Times-Picayune. He had joined the faculty five years earlier, fresh out of training at the University of California, San Francisco, and Johns Hopkins University before that, out of a desire to help the downtrodden of New Orleans, he has said.

All but five of Wiese’s residents returned, and the medical school underwent a revival that he was credited with helping orchestrate. Applications rebounded, faculty ranks filled back out, and new primary care clinics sprang up across the city.

Wiese went on to become senior associate dean of graduate medical education, meaning he oversaw all of Tulane’s residency programs and reported to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the private nonprofit that accredits post–medical school training nationwide. He brought in over $40 million in grants and won more than 50 teaching awards, including six from Tulane, according to his résumé. Around campus, he cut an unmistakable figure: a cowboy boot–wearing Oklahoma native, a former college football player who called himself “coach” and residents his “team,” a nationally respected educator whose letter of recommendation carried serious heft.

“He’s one of those very charismatic leaders who draws people to him,” said a former internal medicine resident, a South Asian woman. “He seemed to enjoy being around us, getting to know us. He took a personal vested interest in all of us.”

Dennar joined him at Tulane in 2008. Born in Brooklyn to a Nigerian mother and an African American father, she was the youngest of four and the only girl, hence the name Princess. In the 1970s, her father’s work on an international culture festival in Lagos meant that their family bounced for years between Nigeria, the US, and the UK before finally settling in southwest Philadelphia.

One day outside their house, when Dennar was around 7, a car hit a boy on a bike. Before the paramedics showed up, she’d decided she wanted to be a doctor. To her surprise, not everyone else would see her as one. When she was a pre-med first-year student at Haverford College, a counselor told her to consider nursing instead. Another adviser, during medical school at what is now Drexel University, suggested she skip the rest of the semester after getting a C on one test. “There’s always this questioning: ‘Are you sure you want to be a doctor?’” Dennar told me.

Those doubts were quelled during her residency at a hospital in Newark, New Jersey, where, for the first time, she had supervisors who were also Black, role models who saw themselves in her. With their encouragement, she set out to master not one, but two, specialties — internal medicine and pediatrics, a combination known as med-peds — so she could help people “from the womb to the tomb,” as she put it.

By the end of her training, New Orleanians were scattered across the country in Katrina’s aftermath. Some wound up as patients at Dennar’s clinic in Philadelphia, talking about how badly their hometown needed good doctors. When she and her husband, also a physician, decided to find work there, the plan was to stay for just one year. But when Tulane announced it needed someone to take over its med-peds residency, the plan changed.

“There’s always this questioning: ‘Are you sure you want to be a doctor?’”

In August 2008, Dennar walked into Hamm’s office for her job interview — one that, in her telling, set the tone for the next decade-plus. Hamm, a kidney disease specialist trained in Alabama and Texas, had at that point been a professor for 16 years and the medicine department chair for three. Within the next five, he’d become dean.

According to the lawsuit Dennar later filed, Hamm told her, “I’m afraid that white medical students wouldn’t follow or rank favorably a program with a black program director,” before adding, “We’ll be comfortable with you sharing a position as co-director” with Tracy Conrad, the white male outgoing director. Hamm has denied making these remarks.

Stunned, Dennar found herself babbling about how she would raise the board-exam pass rates, she recalled. On the drive home, she cried.

Still, she couldn’t say no to the offer. Here was a chance to be the leader she’d always craved, a mentor to a new — and more diverse — generation of doctors.

It took more than a year for her to become the sole director in title, she said, even though she was doing 100% of the work the whole time. (Conrad died in 2014.) But the power struggle had just begun. Since her med-peds trainees divided their time between two specialties, Dennar knew she needed to collaborate with the stand-alone pediatrics and internal medicine programs while ensuring that their unique needs and goals were being met. As the internal medicine residency director, Wiese was a critical partner. As the head of graduate medical education, he was also her boss.

Shortly after Dennar took full control of the med-peds program, Wiese started requiring residency directors to use a rating system he developed, known as Atlas, to measure applicants based on factors like their test scores, class ranking, and the perceived quality of their medical school, according to her lawsuit.

On a list ranking 151 institutions, according to a 2015 Atlas spreadsheet I obtained, Meharry Medical College was the highest-ranked historically Black medical school at 104, followed by Morehouse School of Medicine and Howard University College of Medicine at 120 and 121. Anyone from a school in the 100s would face a significant statistical disadvantage for that reason alone, according to the spreadsheet’s formulas.

Wiese considered Atlas an “objective” screening tool, according to an email quoted in litigation. Dennar found it discriminatory.

“I learned early,” she told me later, “that I had to be very careful with how I interacted with Wiese.”

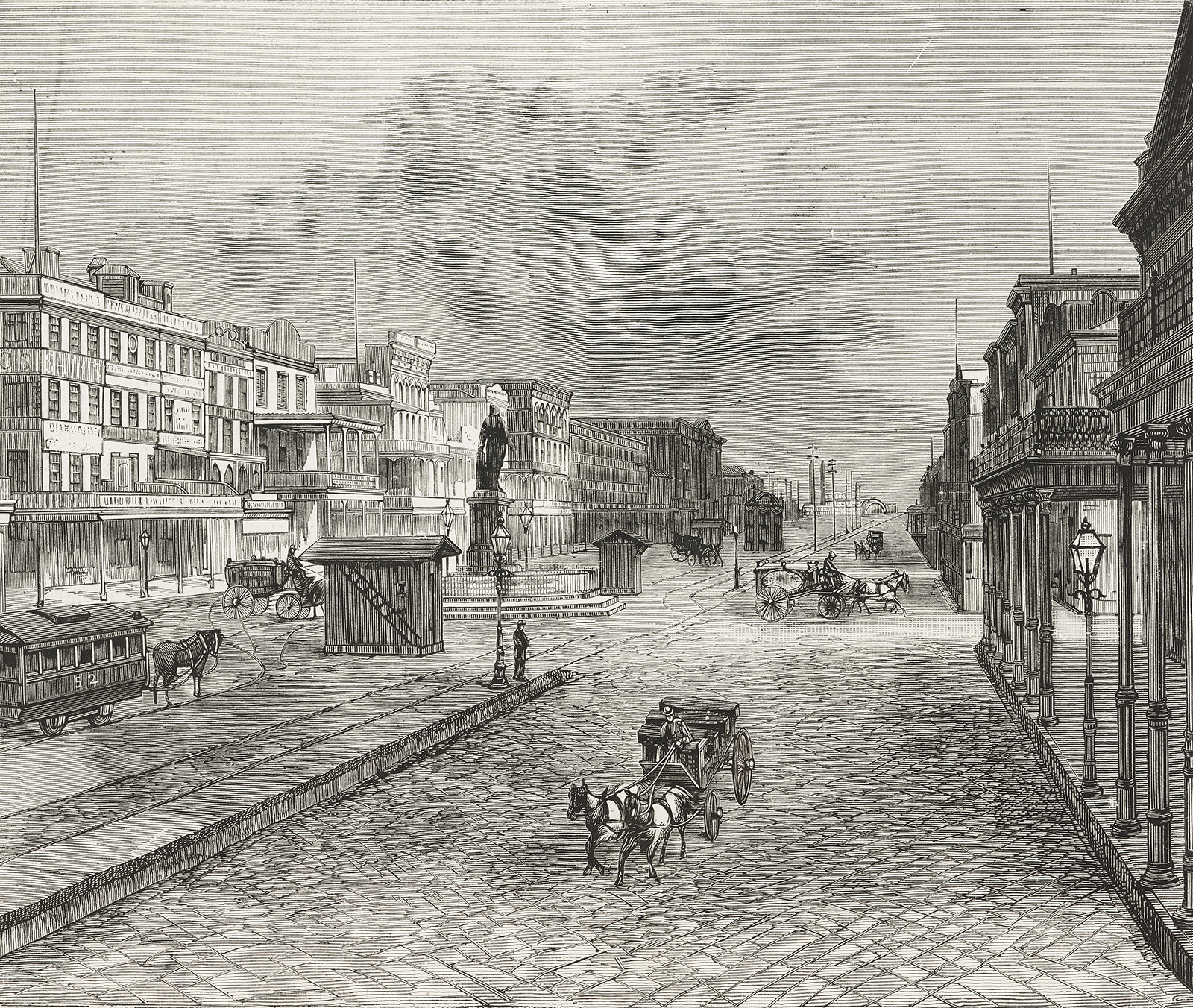

In the 300 years since New Orleans was a French outpost on the Mississippi, racist policies, scientific beliefs, and medical systems have fostered deep health disparities in the city. Public health officials once blamed yellow fever and tuberculosis on nonwhite people’s supposedly criminal nature. Black neighborhoods were clustered in poorly drained areas and built on toxic landfills. For years after integration was federally mandated, Louisiana hospitals kept turning away Black patients.

Founded in 1834 and funded by revenue generated from the state’s slavery-based economy, the Medical College of Louisiana helped widen these inequities. Its faculty included Rudolph Matas, a surgeon for whom the medical school library is named and a fierce opponent of miscegenation. In 1884, the public university encompassing the medical school was reorganized as private Tulane University, a fulfillment of retail tycoon Paul Tulane’s wish to fund the “intellectual, moral and industrial education among the white young persons in the city of New Orleans.”

In 1910, when educator Abraham Flexner published recommendations for standardizing physician training, he found the South “overcrowded” with medical schools led by outdated practitioners. The “men of modern training” at state-of-the-art Tulane made it “one of a very few existing southern schools” worth saving, he declared. But underresourced Flint Medical College, New Orleans’ only school for Black doctors, was “hopeless.” Five of the nation’s seven Black medical schools closed after Flexner’s report, depriving the workforce of an estimated 35,000 Black physicians. Tulane’s medical school did not desegregate until 1967, three years after the Civil Rights Act.

Peel back New Orleans’s charms — spicy seafood, swinging jazz, boozy Mardi Gras nights — and the consequences of this history are clear. Today, Black New Orleanians are significantly more likely than their white neighbors to die from diabetes, cancer, and heart and kidney disease. The city is 60% Black and 35% white, but three months into the pandemic, Black people there accounted for 77% of COVID-19 deaths and white people less than 20%.

Former medical residents said they came to Tulane to right those kinds of injustices, a mission that Dennar prioritized. Believing that doctors should care for their community in every sense, she sent her trainees to volunteer at homeless shelters and educate shoppers at Walmart health fairs.

When Ocheowelle Okeke was finishing up at the University of Mississippi’s medical school and interviewing with different residencies, Dennar made a lasting impression. “This is a very strong, intelligent, not just Nigerian woman, but also a great mentor,” Okeke, a Mississippi native and Nigerian American in her mid-30s, remembered thinking. So Tulane was an easy number one pick during the annual “match,” in which applicants rank their top programs and, if all goes well, get assigned to one of them.

All six residents in the med-peds class who would graduate in 2018 were women of color, the first time that had ever happened at the medical school. Four of them, including Okeke, were Black.

In contrast, none of the pediatrics- or internal medicine–only residents who finished their training in 2018 were Black, according to data provided by Tulane in litigation. Six pediatrics residents were white and two were Asian. In internal medicine, 26 of 29 were white.

Residency is a potentially exploitative experience all around, critics say, where young physicians are routinely overworked, earn $64,000 a year on average, and have little bargaining power. But this crucial training period before becoming independent, fully certified practitioners can be especially hard for women and racial minorities. One survey of nearly 7,700 emergency medicine residents found that 60% of women experienced gender discrimination and 35% of nonwhite respondents faced racial discrimination. In a 2018 paper, Black, Hispanic, and Native American residents recounted patients who mistook them for janitors and colleagues who grabbed their hair and saddled them with fixing diversity-related problems.

As a child who loved to pretend-heal her playmates, Okeke looked up to uncles who were physicians and assumed that she’d someday become one too. But Black patients at Tulane were often surprised to see her walk in, which surprised her in turn. “C’mon, we’re in the heart of New Orleans, where most of the patients look like me,” she said. “Why aren’t there enough doctors here that look like me?”

In America, Black babies have the highest infant mortality rates, women the highest maternal mortality rates, and men the shortest lifespans. Black patients are more likely than white ones to receive later-stage diagnoses for some cancers, and less likely to receive needed pain treatment and specialty care referrals. In efforts to narrow these disparities, Black physicians and other providers are considered critical. Research shows that a diverse workforce is key to improving patient communication, and that when seen by Black doctors, Black men are more likely to get preventive care and Black newborns to survive.

But caring for patients of the same race can be a lonely burden. “Maybe you feel like some of the people on your team aren’t seeing these patients as whole people,” said Damon Tweedy, an associate professor of psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine and the author of Black Man in a White Coat: A Doctor’s Reflection on Race and Medicine. “How do I navigate the fact that my supervisor might say things I think are problematic, but I’m just the person who’s junior and I’m trying to move up the ladder?”

Okeke said she felt alienated by some of her coworkers. According to her, a white supervisor would ask questions like “Who amongst us is more likely to get sarcoidosis?” — which disproportionately affects African Americans — and point at her in a room of doctors-in-training: “You are.” The same thing happened with sickle cell patients, she said. “As long as it was a predominantly African American disease, he always made it his business to point me out and say, ‘You’re the one to get this.’” (Okeke declined to name the physician. Another med-peds resident, Veronica Johnson, recalled Okeke telling her about these discussions.)

Melissa Watts, another classmate, recalled an internal medicine physician who incorrectly insisted he had worked with her two weeks prior. She concluded he must have confused her with another Black resident. “Y’all seem to know Michael from Billy from Sean, come on,” Watts said.

She and other Black women felt certain that their white colleagues treated them differently, and they tried to prove it in part by quantifying disparities in their work schedules. But mapping systemic racism onto calendars would be harder than any of them anticipated.

As the women tell it, the issues began every spring with the internal medicine department’s scheduling meeting, when residents took turns picking desired shifts and vacation days as if in a fantasy football draft. Their chief residents — midlevel supervisors right out of residency — would take notes on a whiteboard, according to a former chief’s deposition and interviews with others present at these meetings. Fingers crossed, the trainees would wait for the schedule to be sent out.

Grueling shifts on hospital inpatient wards, especially overnight, and in intensive care units meant your outside life was over for weeks at a time. But highly coveted electives in subareas — like cardiology or infectious diseases — rounded out your training and, best of all, freed up nights and weekends to study for the career-defining board certification exams. All these requests had to be juggled with the needs of Tulane’s affiliated hospitals, including a 1.7 million–square-foot veterans medical center that opened in late 2016 to replace the one destroyed during Katrina.

For med-peds residents, scheduling brought the added complication of trying to complete both internal medicine and pediatrics requirements — a puzzle with little margin for error if they wanted to finish in four years.

How the schedules came together after the whiteboard meeting was, to some, opaque and angering. The Tulane Seven, who trained in med-peds from 2014 to 2020, alleged that Wiese had assigned them or directed others to assign them a “more difficult and intensive” hospital schedule with “excessive amounts of high service-demand rotations,” while white internal medicine residents enjoyed easier workloads, according to lawsuit filings and complaints they later submitted.

Wiese and Tulane have maintained that residents across the programs got the same amount of demanding rotations, even if their schedules weren’t identical. Wiese has said that other administrators, namely the chief residents, were the ones who created the schedules and communicated with Dennar. “I had nothing to do with individual schedules,” he said in a deposition, adding that his only role was to annually “review it from a financial perspective.” Scheduling, he said, was obligated to prioritize the hospitals’ needs. “The hospitals that pay for these positions own these positions,” he wrote in one email, “and the University merely has stewardship over how they are assigned.”

“No matter how much you tried to advocate for yourself, it just never worked out in your favor.”

But in interviews and depositions, Dennar recalled Wiese as being very involved in schedules. Every time the two of them agreed on one, she said, he would send out a different one — leaving her off the email — and refuse to make changes she requested. In a deposition, another internal medicine administrator also said that Wiese and the chiefs were the ones who ironed out the schedules. It should have worked, Dennar told me, as it did with pediatrics: She would send a schedule to the director and chiefs, and together they’d fix errors and adjust for needed coverage before distributing it.

Time and again, Black med-peds residents said they were told that their desired shifts were taken, or that they were needed on the wards more.

“No matter how much you tried to advocate for yourself,” Johnson said, “it just never worked out in your favor.”

The ACGME gives institutions wide discretion over scheduling. Med-peds residents and internal medicine residents must fulfill the same requirements, only the former has two years to do what the latter does in three, and must spend an additional two years on the pediatrics side. Dennar said the internal medicine residents were supposed to work 45 weeks’ worth of wards. The 17 white male residents who finished in 2018 came close, averaging about 46.5 weeks, according to an analysis of calendars released in litigation.

But the four Black med-peds trainees in the class of 2018, who Dennar said should have spent about 30 weeks on the wards, exceeded that amount, averaging about 41.5 weeks.

Some of them said this lopsided share of the toughest, longest shifts robbed them of time in other areas, including studying time. From 2012 to 2020, Tulane med-peds residents passed the internal medicine certifying exam at an average rate of 82%, according to the American Board of Internal Medicine. For internal medicine–only residents, the average pass rate was 91%. Dennar told me that when directors are not given resources to support their residents, it creates barriers to passing. (The pediatrics board declined to release equivalent data.)

Okeke, Watts, and Rachel Clark, a third Black trainee, said they were unable to complete a required “one-month experience in the emergency department” — car accidents, gunshots, and the like — “during the first or second year.” Shifts labeled “ED” and “ER” are not listed on their schedules until midway through their final year, and none had four weeks of it.

Tulane and Wiese argued that they were given their full time, just partly in differently named shifts that involved admitting ER patients to other parts of the hospital. But Dennar and the current internal medicine residency director have argued that this was not true emergency training, because doctors weren’t triaging wounds. Dennar said that she certified Okeke to graduate out of deference to Wiese — but “I have concerns that she was not given the equitable educational experience as to her white male counterparts,” she said in a deposition.

In spring 2017, Dennar reassured her team that anyone who hadn’t had four weeks in the ER would complete that time during their final year. Behind the scenes, though, Wiese told her that ER time was a “useless rotation,” she said in a deposition, and that “they didn’t need it for their boards.” Dennar resisted, and after a survey confirmed that trainees did want it, Wiese “agreed that the residents would get 4 weeks ER elective as a default,” she later said in an email, recounting their discussion.

But when the schedules came out, Watts was furious: She had just one week in the ER.

“I am asking that 3 more weeks be included in my schedule given that is a graduation requirement I need and I have completed none so far,” she wrote in an email to an internal medicine chief. She’d been given a week in the ICU, but, having done 16 weeks already, she was maxed out. Could she do the ER instead?

“I can understand your concerns,” her supervisor replied. But he would need to ask Wiese because “we rely on him to help us in terms of understanding ACGME requirements.”

Wiese’s verdict: “I am fine with extra time, but it will come in lieu of elective time, not in lieu of ICU.” He then made it clear to Dennar that he was tiring of the pushback.

“Getting to be a real entitled problem,” he told her by email on May 7, 2017.

“If med peds residents cannot contribute their proportional share” of labor, he added, “we might need to re-examine” the “program size.”

One night early in her residency, Okeke said, she took a group of applicants to a party at Wiese’s mansion in the oak-lined Garden District. After their host opened the door, he introduced himself to the prospects — and to her.

“He started shaking my hand,” Okeke said. Because Wiese didn’t seem to recognize her, she concluded that he must not know she was a current resident. She remembered trying to laugh off the awkwardness she felt: “Dr. Wiese, you’re so funny.”

Black med-peds residents tended to have one of two impressions of Wiese, according to seven of them whose time at Tulane spanned a total of 13 years. Some said their interactions were nonexistent, or brief but positive: One remembered him as “very cordial and pleasant.” But others said that Wiese never called them by name, to the point that it was offensive. “He never acknowledged my presence,” said Chioma Udemgba, who graduated in 2020. “It’s a small thing, but it speaks a lot.”

In her lawsuit, Okeke cited the handshake and other, similar interactions as evidence of Wiese treating her unfavorably because of her race. Wiese denied that he racially discriminated against her. Tulane’s attorneys argued that there was “nothing objectively offensive about these events.”

Nonwhite physicians are much more likely than white physicians to leave a job due to what they say is discrimination. At academic medical centers, which combine clinical care, research, and teaching, underrepresented minority faculty members have little mentorship, report facing racial bias, and have lower odds of being promoted, studies show.

Emergency physician Uché Blackstock, formerly of New York University’s medical school, said racism and sexism drove her to leave the faculty in 2019. (An NYU spokesperson said, “We are wholly committed to fostering an inclusive workplace and take all allegations of racism and sexism with the utmost seriousness.”) Pediatrician Benjamin Danielson resigned from a Seattle clinic in 2020, citing racism in its parent organization, a concern that an investigation found to hold merit. (A Seattle Children’s Hospital representative said that it is pursuing a new equity plan as a result.)

That same year, Aysha Khoury alleged that she was suspended, then let go, from Kaiser Permanente’s medical school after leading a student discussion about racism in medicine. An email told her that her suspension “was prompted by a complaint about certain classroom activities,” according to a lawsuit she filed. (A Kaiser spokesperson said, “We strongly disagree with Dr. Khoury’s characterization of events or any assertion that she was removed from her role because of anything to do with race or racism,” and that Kaiser encourages faculty members to share their experiences about those subjects. The spokesperson said the company could not elaborate on Khoury’s claims due to the pending litigation.)

“We’re not at decision-making tables,” Khoury said of Black doctors. “We’re not treated the same way. We’re not as protected in the same way as our counterparts.”

But proving that this kind of treatment is illegal discrimination can be deeply challenging.

While at Tulane, Okeke said she was constantly taken off shifts or asked to be taken off shifts to cover for others. “Every time they needed someone, I was pulled,” she said. She claimed the internal medicine chiefs denied her request to block out time for a rheumatology research conference — while their own residents seemed to have no problem getting such trips scheduled — and that she had to find replacements for her shifts herself. When she wanted to train at an out-of-state hospital for a month, she said, she was told she must use vacation time to get paid, even though a white resident in internal medicine told her that he didn’t have to use his off days to get paid for a rotation outside Tulane.

Tulane’s attorneys argued that there was no evidence that “any of these ‘slights’ related to her race or gender,” and that Okeke was overlooking other factors that could explain the differences. They said that there was no evidence that she was disproportionately called on for backup — schedules made public in litigation do not reflect such last-minute changes — and that there was “only one time” she had trouble getting coverage for herself. They pointed out that the internal medicine resident was in a global health track that paid for him to do research abroad, and that half of her time away got funded in the end.

These complaints were not universal among residents of color. “I can’t really say I personally felt like I was being treated different because I was Black,” said Darlonda Harris, a med-peds resident who graduated in 2017. Gifty-Maria Ntim, a Black alumnus from the 2011 class, said that she was able to easily resolve the few scheduling issues she had. Christopher Salmon, a biracial internal medicine resident who graduated in 2019, said that Wiese had supported his desire to become a cardiologist. “He was actually a big pull for me to be here,” Salmon said.

One Monday in May 2017, not long after the schedules were released, dozens of residents, including from med-peds, gathered in a classroom for their weekly medical lecture, to be delivered that day by Wiese.

According to Okeke, Watts, and Clark, Wiese proceeded to scold certain residents — everyone knew he meant them specifically, they said — for complaining about ER time. He said that people needed to be “team players” and dared the audience to report him to the ACGME, adding that he would take “a slap on the wrist,” according to lawsuit filings, affidavits, and interviews with the three residents. “The buck stops here. I control the schedule,” Watts recalled him saying.

“It came out of the blue, completely out of the blue. We were shocked,” Clark told me.

Wiese has said that he was trying to emphasize that “everybody” needed to do their share of work and denied challenging anyone to contact the ACGME. “I think what was communicated in that meeting is that we were satisfying this detailed requirement in different ways,” he said in a deposition.

“We’re not at decision-making tables. We’re not treated the same way.”

Around the same time, Tulane was looking into a racial discrimination complaint from within internal medicine.

Shortly after Trenell Smith started working as an administrator for the med-peds residency program in early 2016, she reported that she was being harassed by one of Wiese’s employees, Temple Byars, who is white. As her supervisor, Byars left her out of meetings she was supposed to attend, made fun of her hair, and told others that she was “ghetto,” Smith told me. (Byars declined to comment except to say that she has “spent the last four years trying to be a better person.”)

Byars resigned after Tulane found that she had committed racial discrimination, but remaining department leaders — including Wiese — took away many of Smith’s duties in retaliation for complaining, Smith claimed in a 2019 lawsuit that remains pending. (In a court filing, Tulane denied that she experienced retaliation.) Smith has since been diagnosed with depression, anxiety, and panic disorder, according to medical records. In March 2020, Tulane told her in a letter it was ending her employment because she was going on long-term disability leave, and that she could reapply if she recovered.

“Tulane is definitely a racist institution and I don’t think anything would change that,” Smith told me, adding, “The good thing is I’m no longer dealing with those people anymore, but I have a constant reminder of what I encountered.”

On June 16, 2017, Dennar served as a witness for Smith in Tulane’s investigation, describing what she viewed as “unapologetic discrimination,” she told me. That, she alleged, was the last straw for Wiese. From then on, according to her lawsuit, he “began a campaign of retaliation” against her and her residents.

By early 2018, Wiese was openly talking about shrinking Dennar’s program.

“I do think that our long-term goal for next year is to reduce Med-peds to 4 positions a year,” he wrote in a Feb. 3, 2018, email to the medicine department chair. As Wiese explained, their split schedules meant they couldn’t easily be used to meet staffing demands at one of the new hospitals.

“There are also some cultural issues,” he added, “that are arising out of the med-peds program because of, I believe, some excessively elevated expectations (and when those excessively elevated expectations are not met, people are unhappy).” Those issues could be addressed with a “more manageable number” of people.

In a deposition, Wiese said that “culture” referred to “educational philosophy” and “had nothing to do with race.”

In March 2018, two med-peds residents transferred into internal medicine. Dennar said that she learned through a group email that she was losing one-third of her cohort — and wouldn’t be getting the head count to replace them — even though Tulane policy states that directors can’t initiate a transfer without approval from a resident’s current director.

“This is unfortunate,” Dennar wrote to Wiese, according to an email made public in court records. “You and I have never spoken about this as the [ACGME liaison] and I would have liked to and should have been a part of this decision making.”

“I understand your frustration,” Wiese responded, but he defended his decision by explaining that filling the slots was a “zero-sum game.”

Of the dozens of ways that Dennar would eventually allege that Wiese had mistreated her, none involved comments about her race. Could this be a personality clash?

No, she said. “I think it’s 100% racism and sexism.”

“I think it’s 100% racism and sexism.”

Mary Beth Alvarez, a former Tulane medical student who later ran its combined internal medicine and psychiatry residency, told me that she considers Wiese “one of my most treasured mentors and teachers.” “I became an internist probably because of him,” said Alvarez, who is half Hispanic. “I remained an educator because of him.”

But she also believes that his treatment of Dennar was racist. Like med-peds, med-psych trainees split their time with internal medicine. And like Dennar, Alvarez said that she routinely clashed with Wiese over their schedules in a culture that she described as “Wiese’s fiefdom.” Yet he seemed more willing to defer to her leadership than Dennar’s, she said, likely because they were longtime friends — and also because she passes as white.

“It is true that her Blackness interfered with her being accepted and getting a seat at the table,” Alvarez said, “whereas my whiteness allowed me greater access, I think.”

Since leaving Tulane in 2016, Alvarez told me that she regrets not sticking up for Dennar. “I feel honestly horrible about that because I could have helped her create a safer space for herself, help her feel less alone,” she said. “I feel like I let her down.”

By January 2018, a severe flu was swamping hospitals across Louisiana, and anger among the med-peds residents was boiling over. Udemgba, who at that point was halfway through her training, later recalled that they were so overwhelmed, patients were waiting for hours.

Over the internal medicine email list, she suggested that everyone air their concerns in a town hall. “Doesn’t seem very effective in getting to a solution as a Team,” Wiese responded.

“But then again, perhaps there is a feeling that a resident, or residents, cannot trust the Team’s leadership for fear of retaliation,” he added, without naming her specifically. “I just cannot remember anything that I might have done that would have even remotely resembled an act of retaliation.” He insisted that “despite the frustration that you might have felt with schedule change and the like, the chiefs have done their job in ensuring our compliance” with the requirements of the ACGME, the national residency accreditor.

At the eventual meeting, Wiese maintained a tone of resolve, according to Udemgba and another resident who was present, Natasha Lee. “He just sat there and talked to the whole program, basically saying, ‘We survived Katrina, we can survive this,’ and then didn’t leave any space for talk or questions, and left the room,” Udemgba told me.

Feeling full of rage and out of options, she and six other med-peds residents fired off complaints to the ACGME and to Tulane’s Office of Institutional Equity that April. “We feel that there has been a pervasive culture of inappropriate, bordering on illegal, practices by the Internal Medicine Program’s leadership,” they wrote in one letter, citing a “system of institutionalized racism.” In her own pleas for help, their director said she felt “trapped” and “bullied” — even as she acknowledged that writing those words “might someday result in termination or loss of any hope of promotion.”

Six months later, Tulane told the women that it found no racial or gender discrimination, though it declined to elaborate on or release its findings. A representative wrote that an outside investigator researched their allegations, reviewed documents, and conducted interviews but came up with “insufficient evidence” of any violations.

But the ACGME did find cause for alarm. It put both the internal medicine and med-peds residencies — as well as Tulane, as a sponsor of residency programs — on “warning.”

Wiese’s dual roles posed an “inherent conflict,” according to court documents describing the ACGME’s findings in fall 2018. A med-peds director should “have the sufficient authority and resources to enact any changes required” “in cooperation” with other directors. But Dennar and Wiese’s relationship was “not collaborative and healthy” — and the latter “seems to have taken decisional command.” Wiese told the ACGME that his “differences” with the med-peds curriculum predated Dennar and that he hadn’t been aware of any race- or gender-related concerns until then, according to the investigative report that I obtained.

The ACGME also confirmed that the graduating med-peds residents had “deficiencies” in their share of time in the emergency department, subspecialty areas, and electives. And to the trainees, it was clear that Dennar’s “relative powerlessness” meant she “appears to lack the ability to achieve a positive outcome” for their problems, the report stated.

But on the all-important question of whether discrimination was factoring into residents’ treatment, the accreditor told Tulane in a letter summarizing its findings that “no evidence to substantiate such claims was found.” At the same time, its report stated that med-peds “has more individuals of color” than internal medicine — “and an association could not be excluded.”

As her classmates went their separate ways after graduation in 2018, Okeke hoped for a fresh start in St. Louis on a rheumatology fellowship. Back at Tulane, now under scrutiny, personnel shake-ups were afoot. Officials informed Dennar that Wiese was getting an assistant — Paul Gladden, a Black orthopedic surgeon — to report on med-peds’ behalf to the ACGME. In 2019, Wiese passed the reins of the internal medicine residency to Deepa Bhatnagar, a South Asian woman.

But, Dennar later alleged in her lawsuit, Tulane began retaliating against her. She said that her access to software was alternately cut off and restored, that she was removed from the medical school email list, that every program director got a corner office in a new building except her, and that she was never promoted beyond the lowest faculty rank, assistant professor. And in another alleged act of retaliation, Tulane started conducting a special audit of the med-peds program. The catalyst, according to officials, was its ACGME “warning” status.

As the audit began at the end of May 2020, protesters by the thousands were marching against police brutality in New Orleans. “I want this message to be crystal clear from the School of Medicine leadership,” Hamm, the dean, told the campus on Juneteenth. “Black Lives Matter.” Okeke’s and Dennar’s lawsuits, filed on either side of that eventful summer, named nearly a dozen faculty members in all, setting off whispers across Tulane. When Dennar requested that racism be discussed at department chair meetings, for instance, she alleged that the pediatrics chair, Samir El-Dahr, said that he was “tired of talking about racism because it gave him a headache.” (El-Dahr did not return requests for comment.)

In spring 2021, a hired consulting firm surveyed the medical school’s diversity climate. The findings weren’t pretty. More than 170 faculty members, staffers, and others expressed concern that leadership was opaque and self-contradictory, and that Tulane’s lack of diversity hurt its ability to serve patients. When incidents were raised internally — including “gender and racial microaggressions, sexual harassment, blatant racist remarks and behaviors and arbitrary application of policies and procedures” — they were met with “insensitive and often counterproductive” responses as well as “blame, retaliation, and silencing,” according to an internal presentation of the results.

“This is a culture that created, that normalized behavior that was racist and sexist."

At least two white women faculty members have accused the School of Medicine’s leadership of sexism since 2019. Lesley Saketkoo, a former associate professor of medicine, alleged in a gender discrimination lawsuit that she experienced a hostile workplace and that Tulane terminated her for protesting. Clarissa Hoff, director of the preventive medicine residency, alleged in an internal complaint last year that Wiese and Hamm have denied funding and support to her program, which comprises mostly women of color. Tulane came out ahead in both situations: It found no racial or gender discrimination in Hoff’s case, and a judge ruled against Saketkoo. Both women are appealing.

Black women who have passed through Tulane saw their experiences reflected in the stories pouring out of the med-peds program. In a letter posted online, an anonymous pediatrics resident wrote of experiencing “institutionalized and personally mediated racism” while training at an affiliated hospital, which included finding a used condom in her purse. (Dennar has said that she spoke to the trainee about the incident.)

“This is a culture that created, that normalized behavior that was racist and sexist,” said Joia Crear-Perry, a former obstetrics and gynecology instructor.

When Tami Chrisentery-Singleton, who led Tulane’s pediatric hematology-oncology division until 2019, learned that Dennar was suing, she told me she felt ashamed, because “I never had the courage to do it.”

She said she felt like she was extra susceptible to scrutiny as a Black woman, even as she acknowledged “that’s very difficult to prove.” Once, she recalled, an employee stormed into her office, angry that she’d spoken with a higher-up about a project. “Her attitude was ‘how dare you?’” Chrisentery-Singleton said. “Would she have ever spoken to any other doctor in that way?”

On Feb. 11, 2021, five months after filing her lawsuit, Dennar found out over Zoom that she was no longer in charge of the med-peds residency. Tulane leadership told the press that her duties as director were “suspended” but eligible for appeal and that she would remain an instructor. Dennar said that the decision had been presented to her as a “termination.”

Her removal, according to university leaders, was recommended by the internal committee auditing the med-peds program. Its findings were not publicly disclosed, and its members’ names were also not released, although leaders said they were a “diverse panel of 15 peers” from Tulane and affiliated hospitals. Dennar said in her lawsuit that their report contained “no criticism” of her “performance as a teacher, researcher, or physician,” an assertion that Tulane has not challenged.

Tulane’s president, Michael Fitts, told the campus that he was “confident that the processes were thorough and consistent with how the Tulane Medical School has addressed similar issues in the past.” Hamm, one of the people on the Zoom call, said in an open letter that he could not comment on Dennar’s lawsuit but stressed the school’s commitment to “an equitable and inclusive community.”

In a blitz of letters, tweets, and petitions, hundreds of alumni, students, faculty members, residents, and outside observers demanded to know why one of Tulane’s few Black leaders had been pushed out of power. Her appointed replacement was Jessica DeBord, who is white. As for why Dennar’s two deputies, both women of color, were passed over, Hamm explained in a meeting with students that one had recently graduated from residency and the other already had “substantial enough duties.”

A group of alumni and supporters pressed for an outside investigation into Atlas, Wiese’s applicant-scoring system. Over email, the organization behind the residency match told them that, per Tulane, Atlas had been used “by only 4 of 45” programs and was being phased out anyway. But the group objected to this reasoning, noting that one of the four programs, internal medicine, was so big that Atlas could have easily affected the student body’s demographics. A group member told me that they never heard back.

On March 1, 2021, Hamm told Dennar that after “careful consideration,” he was open to reinstating her — with stipulations like executive coaching to “help ensure that issues raised in the special report do not reoccur,” as he described it in an open letter. But Dennar found it “humiliating” that, after more than a dozen years of proving herself, she would face extra scrutiny. “I cannot accept such an ‘offer,’” she replied.

In heartfelt testimonials, 14 of Dennar’s graduates praised how she had demanded excellence, counseled them day and night, and even turned in a letter of recommendation right after giving birth. “This is an incredible loss to Tulane, future trainees and the New Orleans community,” wrote Leah Bruno, one of the non-Black med-peds graduates of 2018. Donations poured into a GoFundMe for Dennar’s legal fees, and with residency match selections due in weeks, a boycott — #DNRTulane, or Do Not Rank Tulane — gained steam on Twitter.

“I don’t need to be a martyr for this program.”

Austin Oslock, who is white, thought Dennar was a “phenomenal” leader, adding, “I wanted to go to a place that embraces people of diverse backgrounds at a time when having physicians that look like and represent their patients is incredibly important.” Farrah-Amoy Fullerton, who is Black, told Tulane’s pediatrics residency program that they would only go somewhere staunchly anti-racist. Daphne Mlachila, a Malawi native, recalled deciding: “I don’t need to be a martyr for this program.”

Vocalizing a problem, however, is easier than finding consensus. Russell Ledet, a joint MD and MBA student at Tulane and an outspoken advocate for Black doctors, told me that he cried over the removal of his cherished mentor. But Tulane’s issues exist to some degree everywhere, he argued, and diverse, talented doctors were harming more than the institution by championing #DNRTulane.

“At the end of the day, you know who really gonna hurt for not coming to New Orleans?” said Ledet, a native of Lake Charles, Louisiana. “The people of New Orleans.”

Racism and sexism have no place in this world. As a former Tulane MedPeds graduate, the traumatic experiences and microaggression faced were immeasurable. I was there for four years and can not imagine experiencing this for over a decade. 🧵 #DNRTulane #DrDennar

Okeke said she would not support an indefinite boycott but added, “I would hope that that movement did bring about Tulane accepting some accountability for their actions.”

Her own efforts to hold Tulane accountable through the courts, however, fell short.

Although Okeke argued that she and the other Black women in her program were harmed by Wiese’s “subjective” decisions, Susie Morgan, a judge for the US District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, said that she failed to identify disparities in their schedules and that Wiese’s alleged actions were too broad to count as “a particular employment practice” under the Civil Rights Act. Examples of specific policies from other workplace discrimination cases included “written aptitude tests” and “height and weight requirements,” Morgan wrote in her late June 2021 ruling.

Okeke’s appeal was also struck down. The higher court agreed with Tulane that she’d failed to demonstrate that her workplace was hostile, discriminatory, or harmful to her career, noting that she was neither demoted nor had her pay been docked, and that she got into her “top-choice” fellowship after graduating on time.

“If I did fail my boards, or if I didn’t graduate on time, then it would be like, I told you, she wasn’t a good resident to begin with — it’s almost like you can’t really win,” said Okeke, who is now a rheumatologist in Mississippi. “If you’re running a marathon and you cross the finish line, that doesn’t mean your muscles don’t hurt.”

On July 2, 2021, the Tulane School of Medicine dropped a bombshell: It was now on probation, and until the ACGME lifted that status, it could not start new residency or fellowship programs and would have to notify all current enrollees and interviewing applicants. Of almost 900 accredited institutions nationwide, just eight are on probation this academic year.

The organization did not publicly specify which standards Tulane was failing to meet. But in response, the medical school pledged to work toward “ensuring that our learning and working environments are inclusive, equitable and free from discrimination and mistreatment,” as well as “reducing our inpatient clinical service commitments and resident workloads on hospital inpatient rotations that have experienced high patient volumes.” Gladden, the surgeon previously elevated to assist Wiese, was promoted to replace him as ACGME liaison altogether.

Tulane’s medical school is now undertaking what a spokesperson describes as “a school-wide cultural change.” It is mandating diversity training, launching a leadership program focused on anti-racism, and hosting events to connect underrepresented medical students with residency directors. Search committees for major hires undergo implicit bias training and include a new assistant dean for equity, diversity, and inclusion.

The University of Missouri’s medical school offers one example of what a path forward can look like. When it risked losing its accreditation due in part to a long-standing lack of students and faculty members of color, it went from an incoming 2007 class without a single Black student to an incoming 2021 class where 20% were racial minorities underrepresented in medicine.

Michael Strecker, the spokesperson for Tulane’s medical school, said it is “committed to recruiting more Black and African-American students, residents, faculty, fellows, and staff.” From 2020 to 2022, he said, its share of Black residents grew from 7.6% to 9%, and Black faculty members from 4% to 5%.

“To suggest that we are not fully focused on these issues and are not making progress on them would be to present a false narrative,” Strecker said.

“So is that how we fix the system? By punishing the person who brought up that these are the issues in the system?”

Dennar resigned on Jan. 1, two days after her case was reportedly settled under undisclosed terms. Breaking the news to her Twitter supporters, she said she felt hopeful about “this new chapter.” “I am the gift that my ancestors gave, I am the dream and the hope of the slave,” she concluded, paraphrasing Maya Angelou. “And so I rise!”

“So is that how we fix the system?” Okeke said to me afterward. “By punishing the person who brought up that these are the issues in the system?”

The men Dennar accused of forcing her out are still there. Wiese, who went on hiatus as the lawsuits played out, returned to supervising residents and tending to hospital patients on Jan. 31, internal calendars show.

This spring, nine professors asked their colleagues for donations as a “surprise tribute” to Hamm’s “dedication, expertise, and resilience during these past twenty-four months” — a period that included COVID-19, Hurricane Ida, and “social and political unrest,” according to their letter. The money would support scholarships, newly established by the dean and his wife, for students who “contribute to the diversity of the School of Medicine.”

This pitch struck some as missing the point. “It was due to blatant acts of racism, bigotry, and ignorance by leadership at Tulane, including Dean Hamm, that led to the cited public social and political unrest within the School of Medicine,” a group of alumni wrote. “Naming this scholarship after Dean Hamm would be to ignore his legacy standing in defiant opposition to attempts to transition Tulane into an era that truly welcomes and supports diversity and inclusion.”

At a campus meeting last fall, Hamm was questioned about his commitment to those values.

“How can we believe any promised changes are actually going to happen,” one attendee asked, according to a recording, “once public attention to the Tulane School of Medicine dies down?”

The dean assured everyone that their future was in good hands.

“You will learn this trust,” he said, “by knowing that you can hold us accountable.” ●